In March 2023, Pacific Wild staff teamed up with content creators Ben Kielesinski and Christian Weiser from Jack Wolfskin, to capture the magic of the herring spawn and trace its connections through the food web.

From sea to land and back again, the team documented some of the most iconic animals in the Pacific Northwest while witnessing the herring spawn turn the cold pacific waters into a Caribbean turquoise. But will the crew manage to see the most elusive dinner guest to the herring buffet? The sea wolf is a grey wolf which has adapted to thrive on the rugged coastline and they are notoriously shy.

Coastal wolves are considered by many to be an Evolutionarily Significant Unit that deserve greater protection and special conservation status. Join us to SaveBCWolves.

Watch this incredible story below of the huge impact of Pacific herring on coastal B.C. in “British Columbia, the Interconnected Coast,” and take action for these #BigLittleFish today by calling for an immediate moratorium on the commercial herring kill fishery and a focus on incorporating traditional ecological knowledge and ecosystem-based management to fisheries in B.C..

Reflections by Ben Kielesinski (video transcript)

Chris and I met on a Jack Wolfskin expedition, where for three weeks we roamed the arid Sahara desert of Morocco. Now I’ve dragged Chris to my home country of Canada where we will join Pacific Wild on a boat on the remote coast of Vancouver Island to witness and document one of the greatest natural events connecting our land and sea.

And how does this adventure start? Well, with these small herring eggs. Each spring along coastal British Columbia, millions of herring laying billions of eggs awaken our coastline from its winter slumber. This not only sustains the herring population, but floods the ecosystem with a biomass that provides nourishment to our aquatic invertebrates and plant life all the way up to our ancient forests and largest mammals.

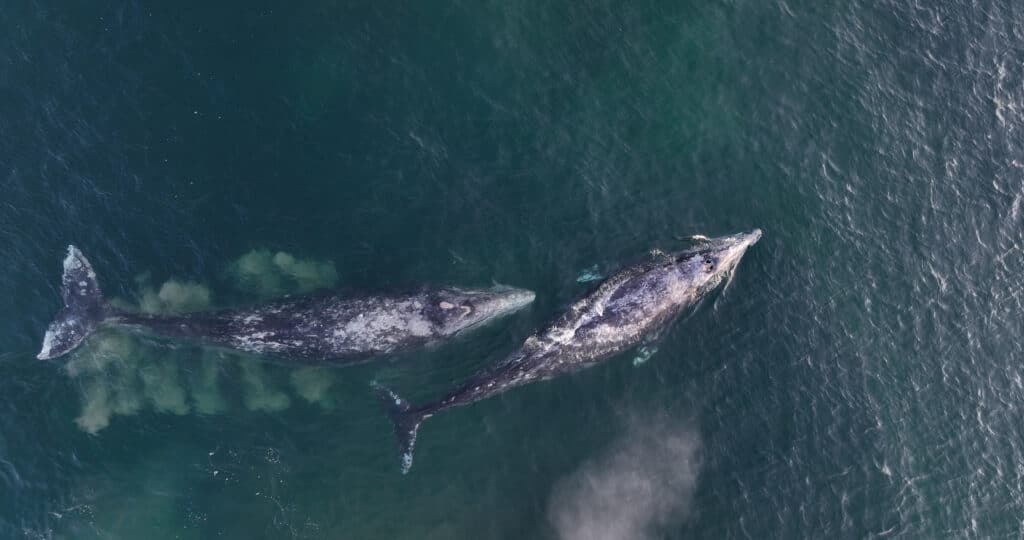

British Columbia is world renowned for our vast, rugged wilderness and diverse plants and animals. And we’re gonna start near the top of the food chain with grey whales.

It’s one thing to see these beautiful creatures from the boat, but to better understand their scale and behavior, seeing them from above is ideal. Luckily, we’ve called in a favor from a local floatplane pilot to scout the area, not only for the whales, but also to see where the herring has been and where they could be going.

Note: All aircrafts are required to maintain a minimum elevation of 1,000 feet above marine mammals at all times in Canadian waters

Home to transient orca, humpback and grey whales, Vancouver Island is a halfway mark for the grey whales’ journey from their summer breeding grounds in Mexico, back to their winter feeding grounds in the Bering Sea, their migration times perfectly with the herrings’ for a little snack to the new family.

There’s only so much my words can do to describe the beauty of these creatures. So I’ll give you a minute and let Chris do what he does best. After battling a night of seasickness, we found ourselves surrounded by dozens of sea otters and watched as they harvested herring eggs from eelgrass behavior that is rarely documented.

Less than a hundred years ago, the sea otters in British Columbia went extinct due to the fur trade, resulting in an increase of sea urchins, which eat the kelp forest at an alarming rate.

Think of sea otters as protectors of the kelp forest feeding on the urchins and keeping balance in the system. These kelp forests are key environments, providing the herring with a nursery to lay their eggs and adolescent aquatic animals protection from predators.

Losing one species can impact the entire system, and luckily, sea otters have been reintegrated to the coast. Birds also benefit from the herring spawn, eating the herring egg-covered kelp and seagrass that was brought to the surface by both the otters and dozens of grey whales dislodging the egg-covered plants right before our eyes.

Whatever is missed by otters, gulls, or whales washes onto shore making another connection to this spawning event: two animals living in separate worlds interacting even though they will never formally meet. Say hello to one of our great land predators, the black bear. It’s early spring here on the west coast, and after a long hibernation, these eggs are welcome nutrients.

We’re fortunate enough to be in the right place at the right time, but even with Chris’ long lens and steady hand, we need stable ground, which means sharing the beach with a 300 pound black bear. But don’t worry, after a week without showering, I’m sure those eggs are a tastier treat.

It might seem confusing how eating this egg salad could sustain a bear-sized creature, but as humans continue to harvest our first growth forests, we’re forcing the local fauna to find new habitats, making it more difficult for predators, such as bears to find calorie-dense food. Then we act surprised when we find a hungry bear rummaging for our trash.

As mentioned, we’re under the guiding hands of Pacific Wild, a non-profit organization that specializes in environmental visual storytelling, advocating for our forests, oceans, and animals that are typically outside of the public view. And now we’re gonna give our sea legs a break and spend some time in a second growth forest.

Chris Weiser: “So what do you think?”

Ben Kielesinski: “If you look up onto the hill here into the second growth forest, you kind of see how almost brown and without diverse life as opposed to the old growth forest we saw a little earlier on, which had, a lot more diversity, a lot more green. It just felt more alive.”

“And even if you listen, all you kind of hear is just the stream behind me, which we should be hearing, you know, different birds because it’s spring, we should possibly be hearing different smaller mammals.”

“And that’s the reality of this second growth forest, is it doesn’t sustain the different ecosystems that we need as opposed to the old growth forest. So, you know, we’re kind of portrayed that second growth forest is as good, but sadly just isn’t because it wipes out so many of the other species that we have here to sustain the rest of the ecosystem.”

Pacific Wild co-founders, Karen and Ian McAllister, visit a tree plantation on Nootka Island

where they planted trees amidst the stumps of an old-growth forest 30 years ago.

This is the information Pacific Wild is bringing to the masses. The remoteness of our coast makes it easy for fishing, forestry and mining industries to get away with harmful practices.

Pacific Wild has had successful campaigns protecting spawning grounds, old growth forests and British Columbia’s grizzly bears from trophy hunting. It’s undeniable. Canada is a natural resource rich country, and it’s crucial to our economy, but our ever-growing consumption shouldn’t be at the cost of our future generations. Our friends, the bears again show the connection between land and sea.

As salmon feed on herring as a main food source, giving them energy to swim upstream to their spawning grounds. Grizzly bears pull hundreds of these salmon onto shore, eating their favorite parts and leaving the carcasses on the banks to be absorbed back into the soil.

Much like the forests, the waters of British Columbia are full of life and diving, although cold, is the most peaceful way to experience the ocean, starfish crustaceans, and sometimes even a curious sealion will take a break from hunting herring to see who may have wandered into their waters.

Throughout our journey, we’ve seen almost every iconic animal from whale to eagle, but Chris and I were starting to lose hope that we would see the elusive sea wolf. This is a species that is adapted alongside the ocean, walking along beaches or swimming from island to island to hunt.

But while I daydream about wolves, we are joined by more grey whales, and Pacific Wild is eagerly taking photos of any exposed fin or tail, because much like our fingerprints, whales have unique identifiers that we can use to better track and understand specific whales or pods.

Our last morning has brought us to Friendly Cove (Yuquot) next to Nootka Island, which in 1778 was visited by Captain James Cook and became the epicenter of coastal colonization in British Columbia.

We’re here because we’ve heard rumors of a wolf population and went ashore to talk to Darrell Williams from the Mowachaht/Muchalaht First Nation.

Ben Kielesinski: “So we just landed here at Friendly Cove, on Nootka. And we have met one of the people that live here, one of the First Nations here, and he has let us know that there are two types of wolves here, grey wolf and sea wolves. But we have to be kind of cautious because we’re going to see the church and then the other side of the beach. But he has scared off two cougars recently. So, we just gotta be cautious and yeah, let’s go see the church.”

Darrell is part of the restoration project of the 70 year old church, adding totem poles and First Nations art from both the past and present to better represent the history of this coast. Living here full-time he is as connected to the land and sea as anyone and gave us hope that we would see our wolf.

Darrell Williams: “If you really wanna see sea wolves at their best, they tend to go along the outside of the reef and scare seals into the middle. And that’s how they catch them. The big grey wolves, they mainly live off the deer and the elk that are on the island here.”

Our adventures start to end. But there’s one rule I believe in for documenting magic. Always be recording.

Chris Weiser: “Oh so that’s why you are writing it all down…”

Ben Kielesinski: “It feels like a goal… I mean come on.”

Chris Weiser: “Wolf wolf wolf!”

We started this adventure last week sharing herring eggs harvested by the First Nations people, unaware of where these tiny ocean jewels would take us.

And now we’re watching sea wolves walk along the edge of the tree-lined beach, searching for the very same herring eggs, almost as a reminder of why we’re here: to witness the connection between land and sea and how important each species from conception to inevitable end, plays a role in keeping nature in equilibrium, allowing people like you, me and Chris to continue to discover the wonders of our amazing world.