The herring roe fishery in the Strait of Georgia (SOG) has come and gone for another year. Despite strong opposition from coastal people, pressure from local politicians and communities, vigorous campaigning from multiple conservation groups, and the advice of her Department’s own scientists, Minister Bernadette Jordan chose to allow this ecologically destructive fishery to take place at the same level again in 2020. In total 9,090 tons of these critically important fish were hauled out of the ocean near Denman and Hornby Islands.

Highlights from 2020

This year, Pacific Wild joined forces with the W̱SÁNEĆ Leadership Council, Conservancy Hornby Island (CHI), Ecologyst, Sea Legacy, and the Association for Denman Island Marine Stewards to raise awareness and garner support for herring conservation efforts.

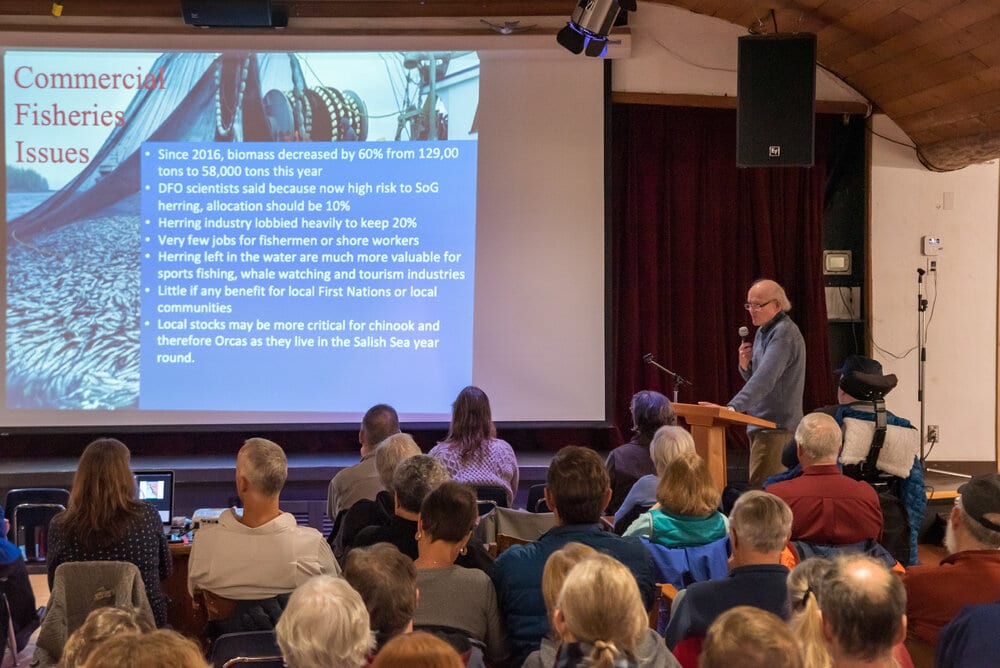

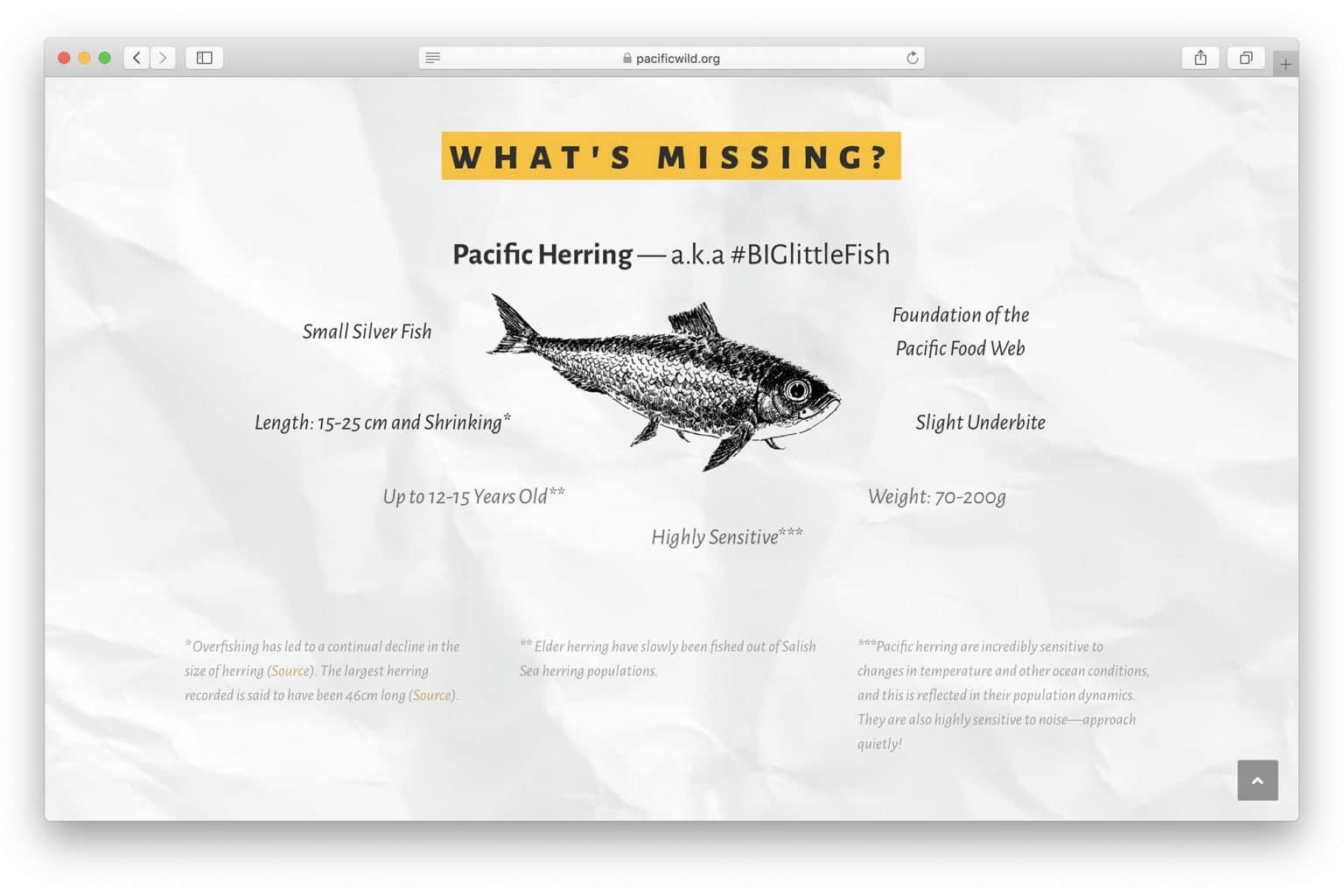

In the lead-up to the 2020 fishery, our team took herring on the road, holding public speaking events in the Cowichan Valley, Salt Spring Island, and Powell River with Eric Pelkey, Hereditary Chief of Tsawout of the W̱SÁNEĆ Nation. We also worked alongside Courtenay-Alberni Member of Parliament and NDP Fisheries Critic Gord Johns on an official House of Commons E-petition which received over 5,000 signatures. This season also saw a new angle on our herring campaign, Have You Seen This #BIGLittleFish?

These efforts culminated in hundreds of caring public descending on Hornby Island for CHI’s fourth annual HerringFest between March 5th and 8th, coinciding with the opening of the fishery and the spectacular spring spawn. During this time, we were happy to see a strong turnout for a follow-up meeting from November’s historic herring forum in Saanich, with representatives from territories all over the island. Throughout the festival, and the spawn, our team was onsite to document the fishery on the frontlines and share stories about the importance of herring with the masses. We were successful in bringing herring stories to the attention of the Canadian public both on social and traditional media.

Government Mismanagement: the Root Cause of Herring Declines

When it comes to the fishing industry, it’s easy for critics to focus on the people on the ground, while resource managers—the ones ultimately in charge of responsible stewardship—remain out of sight in their government offices. We want to take this opportunity to acknowledge that our visuals have featured herring fishermen, and to emphasize the need to focus on management, and not the people who make a living on the coast.

Our organization’s opposition to this fishery comes down to Fisheries and Oceans Canada’s (DFO’s) widely criticized and evidently flawed management practices, which have led to the closures in four out of five herring fishing regions. As the governing body responsible for determining fishing quotas, DFO’s goal is to create a situation that maximizes the catch each year without causing the population to collapse. It’s a flawed strategy considering the Department’s mandate has outlined the importance of rebuilding fish populations and incorporating modern safeguards so that fish are protected for future generations. DFO’s current approach has a track record of failure for not only herring, but a myriad marine species Canada-wide. This brings us to the high-risk situation we’re in today for a species that forms the foundation of our coastal ecosystem.

To determine allowable catch rates, DFO first needs to estimate how many herring are in the ocean. They use a variety of statistical modelling methods to estimate population biomass using pre-season and in-season soundings and dive surveys as well as aerial surveying of spawning events. But within these western scientific approaches, there’s a huge margin of error. In fact, last year, DFO biologists overestimated the number of herring in the SOG for the 7th time in the last 13 years, which led to another year of overfishing—catching approximately 25% of the estimated population.

The risky 20% harvest rate, initiated in 1983, is still applied year after year. On top of this, DFO compares its estimates to data from 1951, even though herring populations were already depleted by the reduction fishery which began in the 1870s.

Smaller Fish, Bigger Problem

North of the border, Alaskan herring returns are experiencing similar trends of declining age classes as in BC—a classic sign of overfishing. Resource managers estimated that more than 80% of the herring returning to Sitka Sound are less than four years old, which don’t meet market requirements for weight. In Togiak, because of poor value due to weak markets, fishermen are choosing not to fish. On March 31st, the Alaska Superior Court sided with the Sitka Tribe and ruled that the Alaska Department of Fish and Game had not lawfully managed the fishery to protect subsistence rights, and the larger case continues in July—mismanagement is happening across the coast, and transcends borders.

Herring Feed This Coast

There are serious consequences to herring mismanagement. These tiny silver fish are the foundation of coastal ecosystems, nourishing many iconic species in British Columbia.

Endangered Chinook salmon rely on herring as one of their primary food sources. 62% of their diet is made up of the small forage fish but dwindling populations are one of the many contributing factors to their drastic declines. In turn, Chinook salmon make up 80% of the diet for endangered southern resident killer whales. But as herring are fished to the brink, Chinook are vanishing and these whales are left with nothing to eat.

DFO has allocated millions of tax dollars to try to save southern residents but none of their methods seem to be working. Meanwhile, due to their poor management practices, the herring that could be feeding hundreds of thousands of Chinook salmon are being caught in this wasteful roe fishery. In an Access to Information and Privacy request, DFO revealed that they have not done any research on the impact of herring on Chinook salmon populations.

In addition to these species, humpback whales, dolphins, porpoises, sea lions, seals, millions of seabirds, like cormorants, murres, and surf scoters, as well as bears and wolves all depend on herring and their eggs as a food source. As overfishing plagues herring populations, there’s less and less food to go around, causing ecosystem-wide changes.

Aside from wildlife, the loss of herring has been called a cultural genocide for coastal First Nations, who have lost access to important traditional food and cultural practices.

The Herring Roe Fishery Supports Disease-Spreading Fish Farms

One of the most offensive aspects about the industrial herring roe fishery is that the carcasses of herring are not used for human consumption. Instead, these fish are ground up into meal and oil that are fed to farmed Atlantic salmon in open-net pens. These facilities are spreading disease and other pollutants into the marine environment and threatening the survival of British Columbia’s struggling wild salmon, including endangered Chinook.

What’s Next

Our #BIGLittleFish campaign in the SOG is supported by many partners including W̱SÁNEĆ Leadership Council, Sea Legacy, Conservancy Hornby Island, the Association for Denman Island Marine Stewards, and Ecologyst, with the help of photographers, filmmakers, scientists, and conservationists.

Moving forward, we will continue to work with local communities, First Nations, and conservation groups to bring public attention to this unsustainable fishery that threatens life on this coast. The word is out and support continues to grow.

Learn more about this campaign, and help spread the word: