For thousands of years, herring had been abundant on the British Columbia coast. Prior to industrial fishing, herring were being fished by Indigenous people using sustainable fishing methods, keeping the returning herring population in abundance. The current Integrated Fisheries Management Plan and the common framework used to manage herring is based on an incomplete picture of past herring populations. The baseline used for estimating biological parameters starts in 1951, when in fact, industrial herring fishing began decades earlier.

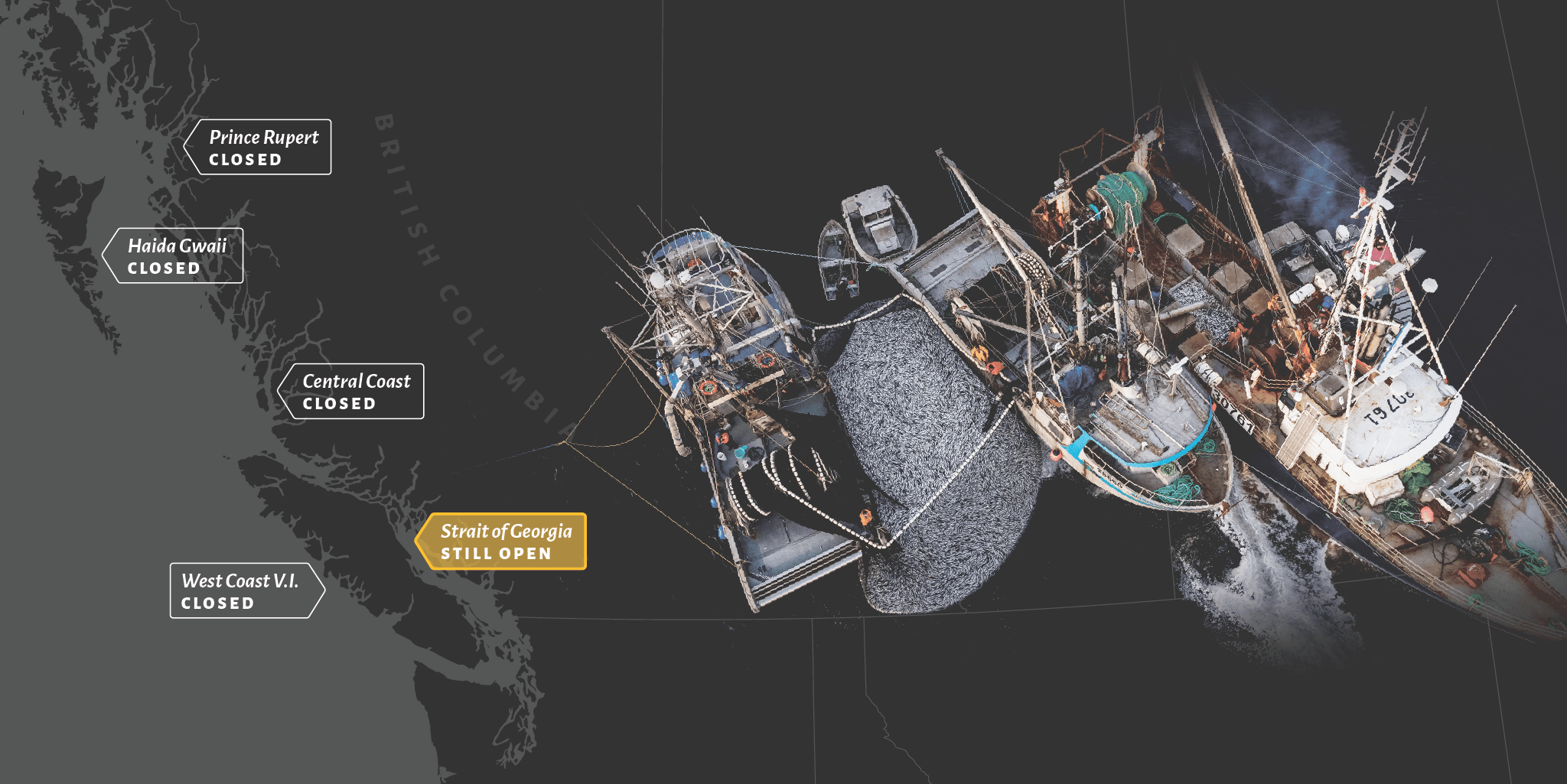

Four out of five Pacific herring fisheries have collapsed. The Strait of Georgia holds the last remaining commercial fishing grounds with the current 2020/2021 IFMP allowing a quota of 20% the assessed biomass. We wait with bated breath for the impact of an additional over-exploitative fishing season. Future management of the herring fishery must be overhauled before this foundational species is fished to extinction.

Migratory and Non-Migratory Herring Populations

Did you know that there is evidence of distinct migratory and non-migratory herring populations? Tagging studies conducted in the 1990s concluded that some herring populations never leave their spawning grounds, suggesting that there is a true non-migratory population (Hay et al. 1999). Researchers found that regional management boundaries may be excluding non-migratory populations from management estimates, allowing non-migratory populations to be overfished.

A recent study by Petrou et al. (2021) entitled Functional genetic diversity in an exploited marine species and its relevance to fisheries management found that there was observed genetic diversity in Pacific herring populations. It suggests that genetic diversity should be recognized in management in order to preserve the ecological, economic and cultural significance of herring.

Historical documents (as outlined in our recent Fighting Fish paper, 2021) show that fisheries managers have long been aware of the management implications that come from grouping non-migratory and migratory populations together in management plans. We call for increased research into genetic distinction in herring populations so that management can properly reflect the ecology.

Read Now: “The Fighting Fish”

Pacific Wild’s new research paper provides evidence that government mismanagement is to blame for substantial Pacific herring decline.

Sources

Casavant, B. & Pacific Wild Alliance (2021). The fighting fish: A historical review of our relationship with pacific herring in British Columbia [policy white paper]. Victoria, B.C.: Pacific Wild.

Hay, D., McCarter, P., & Daniel, K. (1999). Pacific herring tagging from 1936-1991: A re-evaluation of homing based on additional data. Ottawa, Canada: Fisheries and Oceans Canada, Biological Services Branch (Nanaimo, BC).

Fisheries and Oceans Canada. 2022. Pacific Region Integrated Fisheries Management Plan, Pacific Herring, November 20, 2021 to November 6, 2022. 22-2124: 223 p.

Petrou E.L., Fuentes-Pardo A.P., Rogers L.A., Orobko M., Tarpey C., Jiménez-Hidalgo I., Moss M.L., Yang D., Pitcher T.J., Sandell T., Lowry D., Ruzzante D.E., Hauser L. (2021) Functional genetic diversity in an exploited marine species and its relevance to fisheries management. Proc Biol Sci. Feb 24;288(1945):20202398. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2020.2398. Epub 2021 Feb 24. PMID: 33622133.