UPDATE Do You Caribout Wolves?

We believe caring about wolves IS caring about caribou. The ongoing destruction of critical caribou habitat is causing their decline and we don’t need to kill wolves to save caribou.

why caribout wolves?

Why are we talking about caring about caribou and wolves? The British Columbia (B.C.) government linked the health of these two species eight years ago when the Province started a taxpayer-funded wolf cull to support the recovery of endangered caribou herds in B.C.. In less than a century, the British Columbia (B.C.) caribou population has declined from around 40,000 to a mere 17,000 distributed among 54 herds of woodland caribou (Rangifer tarandus caribou).[i],[ii] Several caribou herds are extirpated (locally extinct) and more are expected to follow in the coming years. The B.C. government admits that the cause of this decline is loss of habitat, however instead of halting habitat destruction, it has invested over 8 million dollars in a predator reduction program primarily targeting grey wolves (Canis lupus). Since the decline of caribou populations in B.C. is caused by ongoing destruction of critical habitat, killing wolves does not solve the problem of caribou decline.

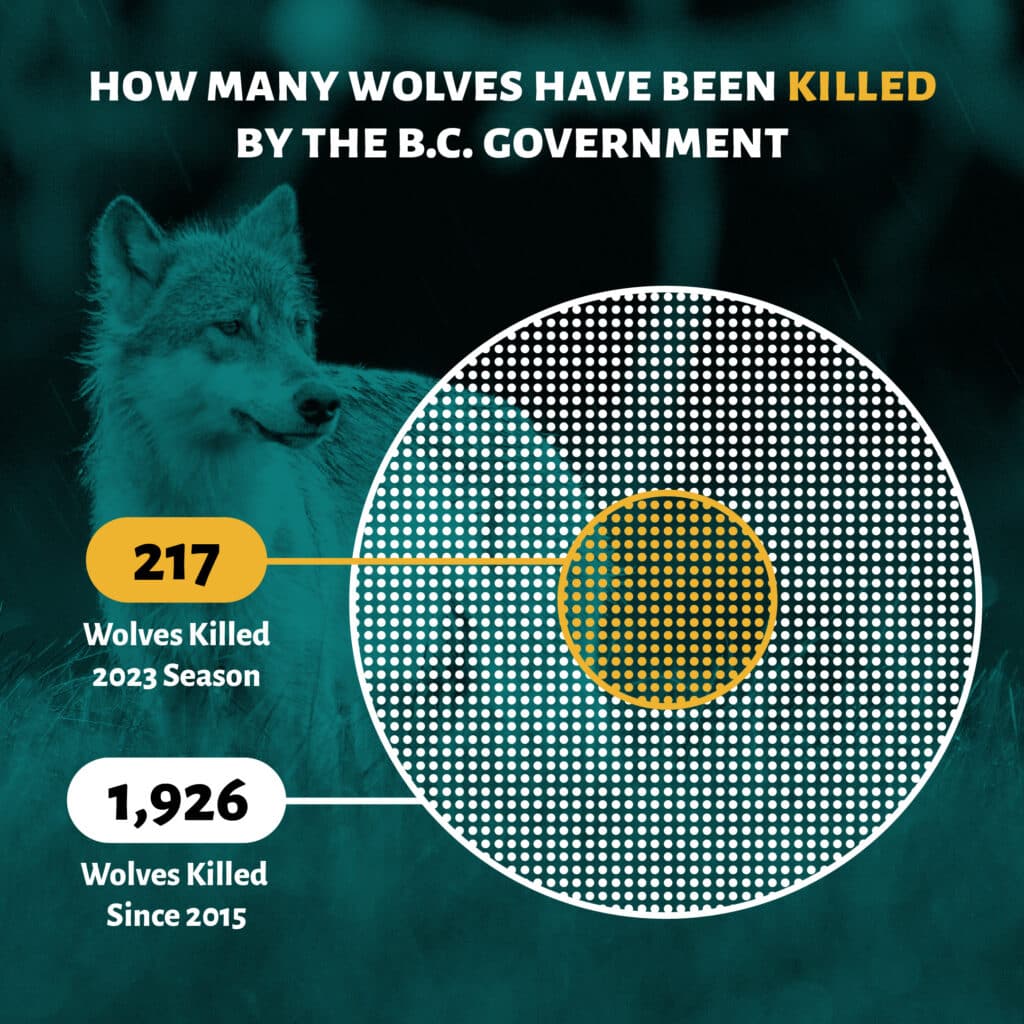

Almost 2000 wolves have been killed since the program started in 2015, along with a smaller number of other predators such as cougars and bears costing taxpayers over 8.4 million dollars to date. The vast majority of wolves have been shot from the air, making the cull not only expensive but also inhumane.[iii],[iv],[v],[vi] Wolves are mostly killed by contracted shooters via helicopter, which often follow one radio-collared ‘Judas’ wolf back to the pack, using the family structure to eradicate more of the pack. Helicopters chase the wolves from low flying heights, creating intense fear, and with little chance of escape. Wildlife experts contend that shooting a moving animal from a helicopter is not in accordance with the Canadian Council of Animal Care (CCAC) guidelines as it is error prone and causes long and painful deaths to wolves[vii]. Furthermore, evidence to support extermination by aerial shooting as a humane method is not adequately documented in the scientific literature.

Recovery means self-sustaining caribou populations. For a species to survive, they require suitable habitat. The provincial wolf cull program is unsustainable,[viii],[ix] unscientific,[x],[xi] unethical,[xii] unacceptable to British Columbians,[xiii] and simply unjust.[xiv] Scientists resoundingly assert that in conjunction with long-term restoration of critical habitat, managing animal movements in the altered landscape to reduce encounters between wolves and caribou offers a cost-effective short-term alternative to the cull.[xv] Experts in Alaska are reporting that the Mulchatna caribou herd populations continued to decline despite decades of wolf and bear killing, largely due to poor body condition from lack of food, and an increase in brucellosis tied to the lack of predation on diseased animals, allowing brucellosis to spread through the herd.[xvi] Apex predators like wolves help regulate species health and play a critical role in maintaining a functioning ecosystem. From songbirds to the shape of rivers, wolves have a profoundly important place in the food web and the landscape.

The Province continues to allow logging and fragmentation of critical habitat in endangered caribou herd areas while scapegoating wolves as the culprits of the caribou’s decline. that 136,229.07 square kilometres of habitat have been lost within caribou herd ranges due to human disturbances. This is equivalent to 86 million hockey rinks or almost 47 times the footprint of the lower mainland. This habitat loss has actually steadily increased since provincial and federal governments were tasked with caribou recovery in 2003. Without protecting and restoring the old-growth forest that caribou depend on, the wolf cull is at best a “palliative measure”[xvii] for the dwindling herds, and stalls the push for true protective action. Therefore, at Pacific Wild, we believe caring about wolves IS caring about caribou.

Photo Mark Williams

WHY HABITAT?

Woodland caribou (Rangifer tarandus caribou) populations have undergone severe declines in B.C. According to federal designations, the Boreal ecotype is classified as ‘threatened’, the Northern Mountain ecotype is classified as ‘special concern’, and the Southern Mountain ecotype was recently assessed by the advising body, Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC) as ‘endangered’, with eight local population units under imminent threat.6 The B.C. Conservation Data Centre (CDC) has identified the Boreal, Northern Mountain and Southern Mountain ecotypes as ‘Red-Listed’, Blue Listed’ and ‘Red Listed’, respectively. 7

FORESTS ARE FOOD

The decline of caribou is one of the toughest conservation challenges in North America. In B.C., caribou are facing a crisis due to habitat destruction. Woodland caribou are food specialists; they depend on old-growth forests which provide abundant lichen as their primary food source. However, industrial logging, mining, oil and gas extraction, and recreational activities have resulted in the direct loss of caribou habitat, as well as the degradation and fragmentation of their habitats. These changes have rendered the land incapable of sustaining caribou populations.

Loss of critical habitat is well-established as the ultimate cause of decline as caribou face overwhelming health stressors as a result of severe nutritional inadequacies and disease.8 Failing to meet dietary requirements such as protein and energy suppress maternal body fat, calf production and growth.9 Widespread depressed body condition and low body fat levels for caribou in B.C. make them susceptible to disease, parasites and predation.10,11,12 Essentially, starvation is causing devastating consequences to reproduction, growth, survival and at a larger scale, decline and uncertainty in the persistence of caribou populations.

HABITAT LOSS COMPOUNDS PREDATION

The altered landscape leads to a secondary pressure, compounding problems for caribou. The cleared land gives rise to the growth of early seral forests, which consist of more open, early‐successional vegetation and shrub habitat. This type of open habitat is favoured by moose, elk and deer, leading to a rise in their population numbers. Moose, elk and deer are the primary prey of wolves, and subsequently invite more wolves to the altered landscape. As these species move into the more open land by way of logging roads, seismic lines and snow-packed trails, and the wolves then follow their preferred prey. Although primary prey species don’t directly compete with caribou, their increased abundance supports higher wolf populations in caribou territory that historically had low densities of both primary prey and predators. Subsequently, wolves have access to caribou. Increased wolf-caribou encounters, mediated by habitat disturbance that supports more primary prey, means increased caribou predation. The indirect interaction between the abundant primary prey and the endangered woodland caribou is ecologically termed ‘apparent competition’.13 It’s called ‘apparent’ because the primary prey and caribou do not interact directly themselves and it may not be immediately obvious that the competition is happening, since the two species are not direct competitors. Simply put, caribou become the wolves’ by-catch. Wolves don’t normally seek out caribou but when they are searching for their primary prey, which now occupy disturbed caribou ranges, coming across an exposed caribou will suffice as a meal. Humans have caused these changes in predator-prey dynamics.14

Moreover, extensive research has been conducted on habitat disturbance in the form of linear features (e.g., logging roads, seismic lines, pipelines, and trails) which directly allow wolves ease of access to caribou (independent of any primary prey considerations). In fact, for many herds in B.C. the science shows stronger support for the direct effects of linear features on caribou-wolf co-occurrence (and thereby predation) than for the ‘apparent competition’ hypothesis.15,16 Linear features reduce the ability for caribou to find refuge from predators and facilitate predator movement to increase spatial overlap of woodland caribou and grey wolves. One study demonstrated that the use of linear features by female caribou increased mortality of newborn calves.17 Despite attempts, caribou are unable to avoid high density linear features. Caribou simply have nowhere to hide.18 There is now a growing subset of the scientific literature dedicated to mitigative solutions focusing on blocking and restoration of linear features.19,20,21,22,23,24

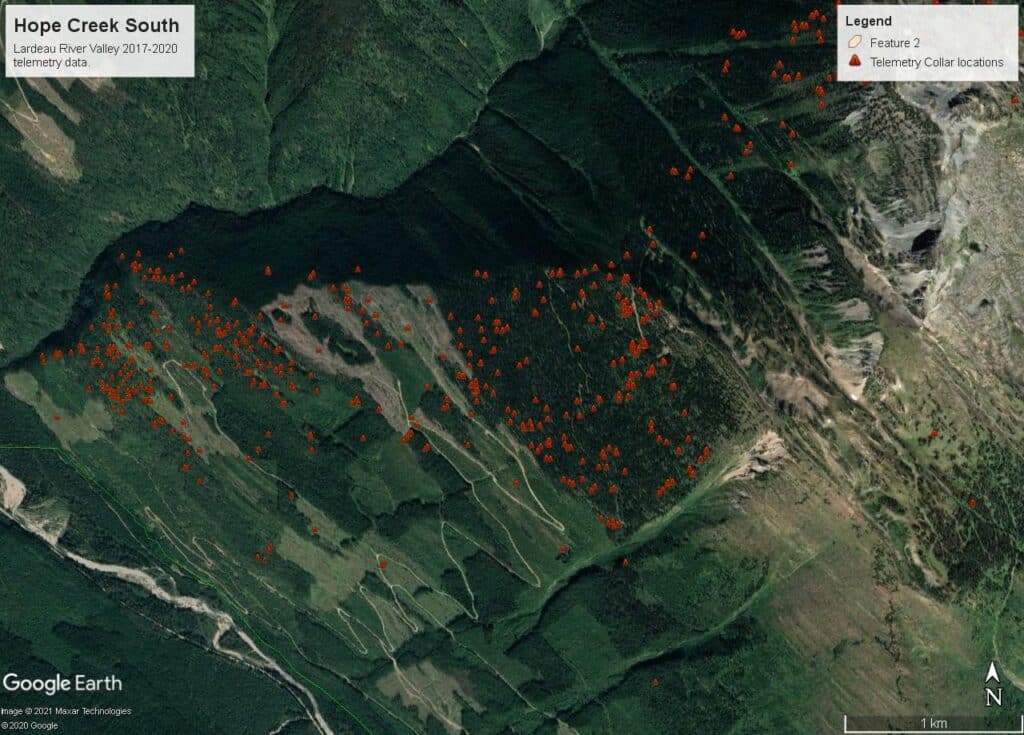

Image: Caribou have nowhere to hide. This telemetry image shows the distribution of radio-collared caribou by Hope Creek in the Central Selkirk herd range. Courtesy of the Valhalla Wilderness Society.

Scientists refer to the human-mediated predation by wolves as a proximate cause of decline, or a ‘top-down’ pressure. However, experts are in agreement that the ‘bottom-up’ forces associated with habitat loss represent the ultimate cause of decline and herd extinction. Regardless, human disturbance means caribou have nothing to eat and nowhere to hide. In addition to the cumulative effects from all forms of industrial development, further cumulative impacts from forest fires, mountain pine beetle, and climate change all add up to exert mounting pressures on woodland caribou.

HABITAT PROTECTION VS THE CULL

In less than a century, the B.C. caribou population has declined rapidly from around 40,000 to a mere 15,000 today, distributed among 54 herds of woodland caribou.27,28 Several caribou herds have become extirpated (locally extinct) with more expected to be gone in the coming years. Despite this, the B.C. government has yet to adequately address habitat loss and has instead turned to controversial methods of collaring individual ‘Judas wolves’ and aerial gunning of packs, aiming to intensively reduce the population of wolves. However, there is a lack of reliable science to indicate that the reduction of wolves is having a meaningful impact on caribou recovery.29,30,31 What’s more is that habitat loss has only intensified despite caribou being listed as an at-risk species under federal legislation and despite provincial commitments to protect critical caribou habitat.32,33,34,35

Federal recovery strategies and management plans released in 2012 and 2014 for woodland caribou specify requirements of undisturbed habitat necessary for achieving the goal of self-sustaining populations. Under SARA (Species at Risk Act), the development of action plans is mandatory to specify the approach for achieving critical habitat conservation and recovery objectives over time. In a study evaluating the effectiveness of policy and plans, published in 2021 by lead scientists including those from Environment and Climate Change Canada, researchers concluded that the rate of habitat loss is accelerating despite federal policy instruments. Notably, loss of caribou habitat in British Columbia and Alberta increased on average across ecotypes by 262%, six to seven years after the release of the federal recovery strategies and management plans for caribou ecotypes.36 The researchers alluded to the lack of species-at-risk legislation outside of federal lands and further indicated that their results support previous assertions that federal policy commitments do not necessarily translate to implementation commitments. In general, Canada has been ineffective in recovering caribou habitat and herds due to gaps between listing, recovery planning, and execution of conservation and restoration. The lead author of the research made the following statements:

“Our findings support the idea that short-term recovery actions such as predator reductions and translocations will likely just delay caribou extinction in the absence of well-considered habitat management.”

“Predator reductions are a palliative measure as caribou populations are prone to returning to decline soon after such actions cease. Further, it is likely that effective predator management would become increasingly difficult, or impossible, as landscape alteration increases.”

“Our study suggests that unless human-related habitat alterations are adequately addressed, the recovery of most woodland caribou populations seems unlikely.”

THE MAPPING: CARIBOU DECLINE AND HABITAT LOSS

Below is a video timelapse showing the changing landscape of the George Mountain and Narrow Creek caribou herds between 1984 to 2022 using the data layers from the larger GIS map. Explore this map to see how caribou populations, habitat disturbance and estimated wolf densities overlap.

WHO PAYS?

How long will it take to restore critical habitat to support viable caribou populations?

Lethal wolf control by aerial gunning (using helicopters) is touted as a short-term recovery action by the B.C. government, while acknowledging that habitat is a key issue for protecting the herds. Proponents of the government predator control program have stated that the wolf cull will need to be maintained until habitat is restored.39,40 Meanwhile, resource extraction continues in herd areas and restoration efforts are critically underfunded. Eight years into the cull, it is clear that intensive wolf reduction has become a long-term endeavour with short-term results, only delaying the urgency of essential habitat recovery and leading to the eventual demise of additional caribou herds.

At the quarterly caribou recovery stakeholder meeting in January 2023, one government official indicated that it would take 40 years of growth for forests to recover, based on the assumption no further habitat is removed.41 Estimates in the scientific literature are generally greater, indicating lichens, essential food for caribou, can take 60-90 years to regenerate post disturbance.42 Some estimates are greater than 100 years.

Taxpayer dollars spent on the cull

The wolf cull program has to date cost British Columbians millions of dollars. As of now, the exact cost to date is not publicly available since the government has not released a comprehensive breakdown of expenses. However, based on various reports and piecemeal information provided by the provincial government44,45,46,37 the total cost since inception of the program in 2015 is estimated at $8.475 million dollars of taxpayers money. To ensure transparency and help taxpayers understand how their money is being used, the government should be releasing detailed reporting of this allocation of public funds for the wolf cull program. This will allow the public to better understand how decisions on tax dollar priorities are being made on their behalf, what resources are being used, and overall efficacy of the program in meeting its objectives.

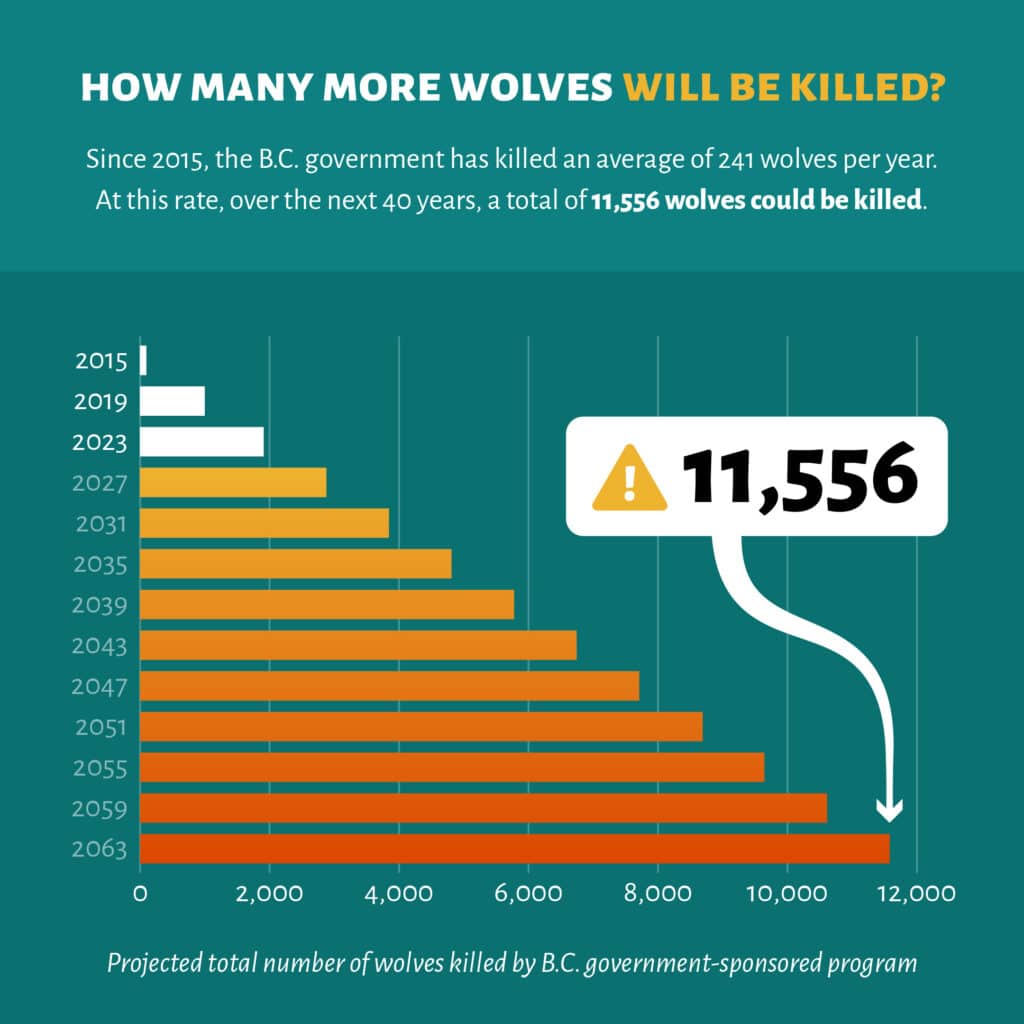

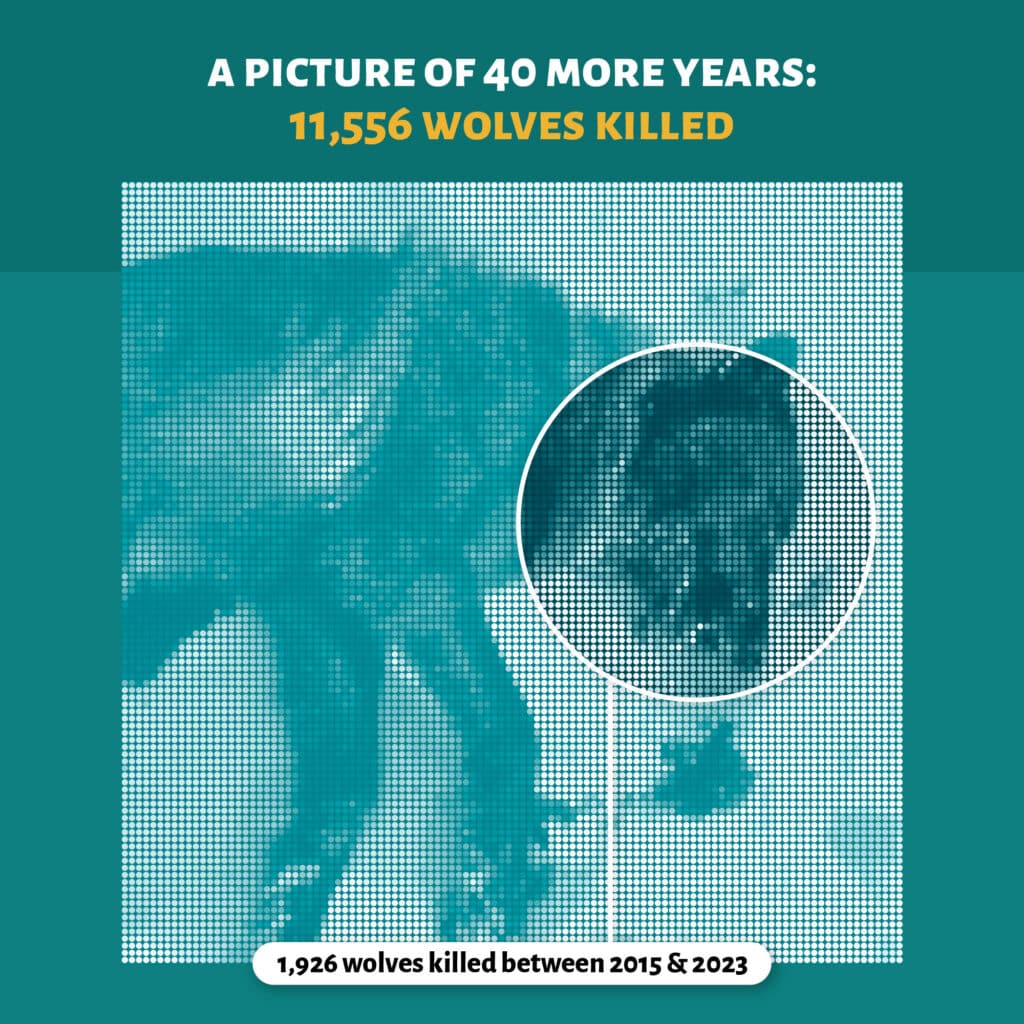

Wolves are paying for these policies with their lives. Records indicate that 1926 wolves have been killed since the aerial culling program began in 2015. Based on an average of 241 wolves annually, we can estimate the number of wolves potentially killed into the future. If the wolf cull were continued for 40 additional years, based on the idea that 40 more years are needed for habitat to recover, then the total number of wolves killed by 2063 (since 2015) would be approximately 11,556 wolves.

This is assuming no further habitat is altered that would thereby favour even more wolves on the landscape. As of now with resource extraction steadily increasing, it is conceivable that the number of wolves on the landscape would be greater and wolf culling would become an exceedingly difficult challenge.

Wolf cull is not the solution

For a species to survive, they require suitable habitat. Recovery means self-sustaining caribou populations. The provincial wolf kill program is unsustainable,48,49 unscientific,50,51 unethical,52 unacceptable to British Columbians,53 and simply unjust.54 Since the aerial culling program began in 2015, nearly 2000 wolves have been persecuted. The long-term impact on predator-prey relationships by a cull program of this magnitude and persistence will cause unintended ecological consequences,55,56,57 and still not address the root cause of caribou extirpation. Constant killing of entire wolf packs on a yearly basis is an enormous waste of resources, with no gain in terms of caribou habitat conservation. The wolf cull is not a sustainable solution to the caribou crisis and is scientifically and ethically indefensible. Scientists resoundingly assert that the cumulative impacts to the land must be addressed to achieve self-sustained caribou populations. Managing animal movements to reduce encounters between wolves and caribou offers a cost-effective short-term alternative solution,58 in conjunction with long-term restoration of critical habitat. (Download citations pdf)

HOW MANY MORE WOLVES WILL BE KILLED?

Current Total and Projections

WHO'S IN CHARGE?

No direct protection for SARA-listed species on provincial lands

There are no specific legal protections for caribou on provincial lands in British Columbia, despite being federally designated as threatened.59,60 In Canada, jurisdiction for the conservation of species-at-risk rests with both the federal and provincial governments, which aim to work cooperatively. This intergovernmental approach was originally set out in the 1996 Accord for the Protection of Species at Risk, agreed upon by federal, provincial and territorial ministers.61 In 2002, federal species-at-risk legislation was enacted, known as the Canadian Species at Risk Act (SARA). This legislation mandates the protection and recovery of endangered or threatened species and their habitats.

Under SARA, the federal government is responsible for identifying critical habitat and for the preparation of recovery strategies, action plans and progress reports for listed SARA species.62 Notwithstanding this, SARA only applies automatically to federal lands, aquatic species, and migratory birds. British Columbia is only comprised of 1% federal crown land. Therefore only a very small fraction of wildlife occurring in areas such as national parks are protected under SARA. For the majority of listed Canadian species with habitat across provincial lands, SARA does not protect them nor their habitat. Management of those species, and wildlife management in general, is under jurisdiction of the Province.

No provincially dedicated species-at-risk legislation

So then, what legislation does British Columbia have to protect woodland caribou? The provincial government undertakes planning and reporting through the provincial Caribou Recovery Program.64 However, unlike most provinces, British Columbia does not have provincially dedicated species-at-risk legislation, representing a major void of any provincially led policy to protect imperiled species. The only legislative tools available to land managers in British Columbia to support habitat conservation and caribou recovery are via some combinations of the Land Act, Wildlife Act, the Forest and Range Practices Act, and the Oil and Gas Activities Act, and under the Environmental Protection and Management Regulation for petroleum and natural gas activities.65,66 All of these pieces of legislation are intended for some other purpose, primarily development, and none of these constitute a stand-alone law with the intent of protecting endangered species and their habitat. Perhaps the most pertinent existing provincial law, the Wildlife Act, is of general application and not absolute; only four species were designated as Endangered under the Wildlife Act (i.e., the Vancouver Island marmot, sea otter, American white pelican and burrowing owl) in 1980 but none since then out of 1909 species identified by the British Columbia Conservation Data Centre.67,68 Therefore, there is no single piece of legislation which has the specific purpose of protecting caribou and critical habitat.69 Without provincially dedicated species-at-risk legislation, this deficiency has significant environmental consequences for threatened and endangered species facing off with resource industries.

Tools for federal intervention

In the case of woodland caribou, the absence of provincially dedicated species-at-risk legislation to protect them and their habitat is a major contributing factor to inaction by the Province, only further necessitating the federal government to take action. In cases where provinces are not adequately meeting established goals and timelines mandated by SARA, there is a regulatory tool available under SARA for the federal government to intervene. Section 80 of SARA allows the Canadian Minister of Environment to recommend an emergency order to halt any activities, regardless of location, that cause further harm or degradation of habitat. The Minister is obligated to recommend an emergency order to cabinet if they are “of the opinion that a listed wildlife species faces imminent threats to its survival or recovery.” However, Cabinet makes the final decision as to whether an emergency order is issued.

Emergency order recommended under SARA

In 2018, the Minister of the Environment formed the opinion that southern mountain caribou were facing imminent threats to recovery and therefore made the recommendation for an emergency order to provide protection. In March 2021, the Government of Canada released a decision statement, in which imminent threats were acknowledged as true, however the emergency order recommendation was declined.70 An ‘approach’ was outlined, citing other measures initiated to address the imminent threats, including:

- Federal funding

- Interim moratorium on new resource development enacted by the Province in parts of east-central British Columbia

- Intergovernmental Partnership Agreement for the Conservation of the Central Group of the Southern Mountain Caribou (February 2020)

Canada–British Columbia - Conservation Agreement for Southern Mountain Caribou in British Columbia (February 2020)

The final decision statement of the rejected emergency order concluded by saying “The Minister will be closely monitoring the implementation of each of the measures described in this Statement. In appropriate circumstances, the Minister could make a new recommendation for an emergency order to provide for the protection of southern mountain caribou.” It is worth noting that an emergency protection order has only ever been issued on two occasions, for the sage grouse and chorus frog.71,72 Decisions to issue an emergency order are discretionary and also consider socio-economic implications of the decision.73,74 In this case, the statement rationale for rejecting the order recommendation for caribou alluded to respect for provincial jurisdiction. Meaning, in the event an emergency protection order is advanced, the federal government is in essence crossing over the jurisdictional line intervening in provincial decisions over resource development.

Habitat degradation continues despite imminent threats

Since implementation of the measures outlined in the federal decision statement that justified declining an emergency order, critical habitat continues to be degraded. In fact, research exploring caribou declines despite legal protections found that from 2019 to 2021, subsidized oil and gas activity occurred in critical habitat.75 Further, the research showed that the provincial wolf cull actually works to sustain the status quo of resource extraction since it satisfies intentions to take conservation action but does not address the root cause. The province continually chooses the approval of industrial activities that impact critical caribou habitat such as oil and gas wells, pipelines and other infrastructure, clearcut logging, and mining over the protection and restoration of caribou habitat.

First Nations’ management and protection of caribou and wolf populations

The Union of BC Indian Chiefs (UBCIC) passed a resolution (Resolution no. 2022-09) calling for First Nations’ management and protection of caribou and wolf populations by territories.76 First Nations uphold the right to make decisions regarding land and wildlife management. Due to lack of Provincial priorities to restore habitat, remove linear features (such as roads, seismic lines and pipelines) and reduce development, the only option for many First Nations is to move forward with Caribou Recovery Plans. The resolution calls for a stop to unilateral state decisions on wolf culling and caribou recovery. While some First Nations are supportive of predator removal, UBCIC Resolution no. 2022-09 demonstrates non-acceptance as well as leadership in cessation of the wolf cull and appropriate caribou recovery.

Federal financial support for old growth protection not accepted

The Government of British Columbia has committed to protecting critical caribou habitat and old-growth forests, but repeated inaction on the ground tells a different story. This is made exceptionally apparent in the wake of an offer of a large sum of money from the federal government to support the protection of old-growth forests in British Columbia. In the 2022 budget, the federal government committed $50 million dollars to help finance the protection of old growth forests on the condition it was matched by the Province. The money would be used to protect the most at-risk forests at low-elevations, characterized by enormous trees in valley bottoms. The Province has yet to accept or match this federal offer. Recently, a motion in parliament seeks to increase the offer to $82 million, if matched amounting to $164 million. 77 Significantly more money would also be available to the Province from the federal Nature Legacy fund of $2.3 billion, which aims to support nature conservation measures across the country, including Indigenous conservation initiatives.78

Canada has engaged in international commitments to halting biodiversity loss79 and to protect 25% of land by 2025 and 30% of land by 2030.80 As of December 2022, British Columbia has also agreed to meet these goals provincially.81 The importance of protecting old growth forests is immeasurable considering that they are critical habitat to many species at risk, are highly productive and support high biodiversity, offer the best solution to climate changes since they hold more than twice the amount of carbon of secondary forests, and provide numerous positive benefits to people (ecosystem services).

Federal intervention remains necessary as as critical habitat and herds continue to disappear

It is clear that provincial priorities and the regulatory framework for species at risk in Canada are failing in the intent to protect at-risk species and their habitat. Evidence from the literature demonstrates that despite federal regulation and provincial commitments, critical habitat continues to be lost at a significant rate, logging is still being permitted and industrial project approvals granted in favour of economics.82,83,84,85 We have already lost thousands of caribou with entire herds being wiped out forever. Conservation biologists and legal experts are calling for effective species-at-risk policy is needed in British Columbia86,87 and have provided recommendations for success. At the fundamental level, the British Columbia government has not ceased harmful activities within caribou habitat, let alone undertaken meaningful restorative actions that promote growth of productive forests to achieve self-sustaining populations of woodland caribou. While provincial commitments to habitat protection and caribou recovery continue to go unmet and even federal financial support is not accepted, it remains that this dire situation, now declared as imminent threats, constitutes immediate federal intervention under SARA. (Download citations pdf)

The resources list titled Intensive Wolf Reduction and Caribou Recovery in British Columbia: Resource List is intended to provide the scientific evidence that supports the dire necessity for seriousness and sincerity in dedication to protection of critical habitat required by woodland caribou (Rangifer tarandus caribou). Further, this Resource List absolves the Grey Wolf (Canis lupus) from being portrayed as the scapegoat by the B.C. government, by substantiating the cull as unscientific, unsustainable, unethical, unacceptable and unjust with considerable evidence documented within the literature.

Chapter topics within the Resources List pertain to threats to caribou, Indigenous conservation, current wolf management, insufficient protection of caribou habitat, inadequate scientific evidence for the wolf control effectiveness, unintended consequences of predator removal, preferred non-lethal methods, ethics research and public disapproval. The document contains over 50 reference summaries from research articles, books, and government documents that are updated on a regular basis.

TAKE ACTION

Tell the federal government to step in to enact emergency habitat protection measures to save B.C. caribou before it’s too late.

Send a message to your MLA in B.C.

Tell your MLA you want an Endangered Species Act for British Columbia, and that habitat protection should be the number one action taken to protect caribou.

GET INVOLVED LOCALLY

Local conservation organizations

Land Use Planning Committees

Community Forest Boards

Speak Out Publicly

donate today to fiona's challenge or sponsor your own billboard

Be like Fiona C. in the Okanagan, who asked, “What can I do?” Out of her passion for saving habitat for caribou and ending the wolf cull, Fiona donated $1000 as a match, one-fifth of the funds needed for our first billboard.

Image Jonah Keim, field researcher and project lead for functional habitat restoration in northeastern B.C.