Table of Contents

#1

A Fishery of Wanton Waste: Out of Sight, Out of Mind and Overboard

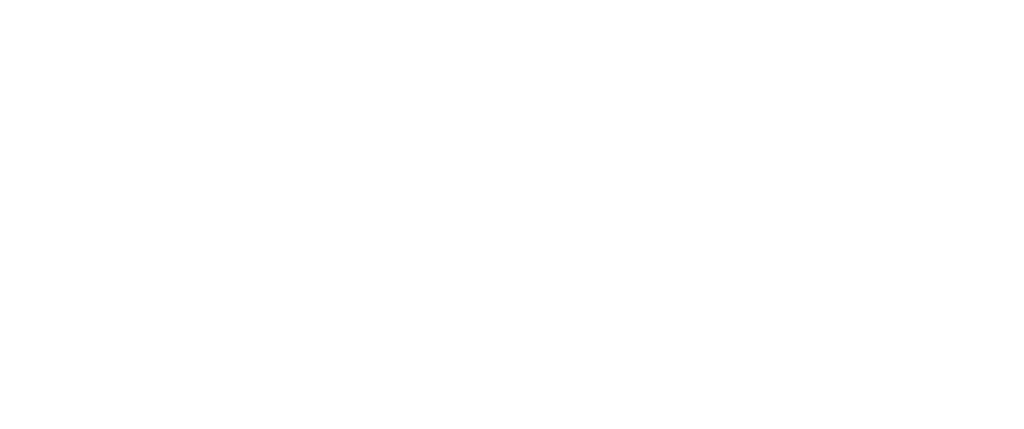

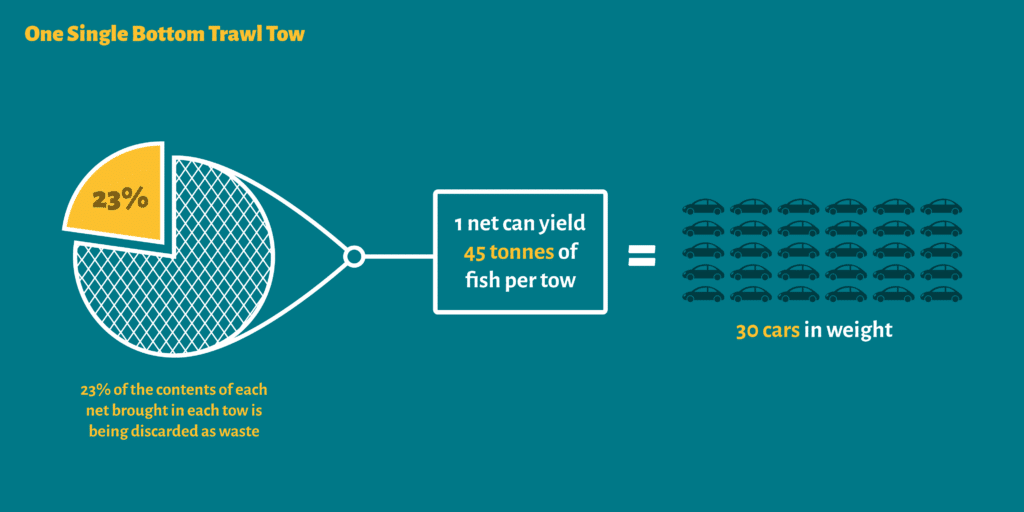

The indiscriminate nature of trawling does not account for the conservation status of species caught and killed as bycatch. Endangered, threatened and globally rare species like the basking shark, Chinook salmon, coho salmon, sockeye salmon, eulachon, sunflower sea star, grey whale and humpback whale all appeared in bycatch records in B.C. within the last decade. In 2023 alone, 10 killer whales were caught in trawl nets in Alaska. Nine of them died.

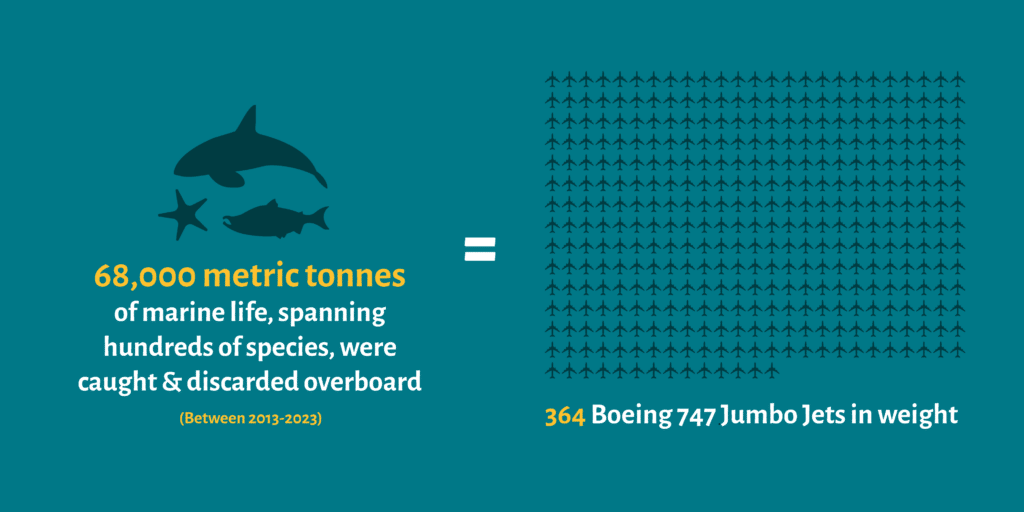

As different species are interconnected in ecosystems, the removal of certain species — like predators — can have cascading effects, affecting the entire marine food web, further contributing to biodiversity loss. Analyses of the cumulative effects of trawling suggest that a single tow can cause an average 55% reduction in abundance of animals in the trawled area. Furthermore, when specific species are considered, such as invertebrates, bottom trawling is estimated to lead to upwards of 68% reduction in abundance. That means one single trawl trip could wipe out more than half of the marine life in its path.

1 Fisheries and Oceans Canada (2024). Groundfish Data Unit. Stock Assessment and Research Division, Fisheries and Oceans Canada. Data provided on August 19, 2024.

2 Fisheries and Oceans Canada (2024). Groundfish Data Unit. Stock Assessment and Research Division, Fisheries and Oceans Canada. Data provided on August 19, 2024.

3 Fisheries and Oceans Canada (2024). Groundfish Data Unit. Stock Assessment and Research Division, Fisheries and Oceans Canada. Data provided on May 2, 2024 and August 19, 2024.

#2

An Undignified End to Irreplaceable Species: 200-Year-Old Fish Reduced to Pet Food & Fertilizer

Fish twice as old as your grandmother, are being ground up and fed to your cat. Some of the species harvested by the groundfish trawl fishery, such as rougheye rockfish and spiny dogfish (mud sharks), are some of the oldest or slowest reproducing species found on the planet. Rougheye rockfish can live to be over 200 years old. There are individual rougheye swimming in the ocean today who were born before cars were invented. With females taking decades to reach sexual maturity, rougheye rockfish are particularly susceptible to population collapse, and there is no recovery from extinction. Mud shark females do not mature until an average age of 35 and pups are retained in utero for 18 to 24 months, one of the longest known gestation periods for any vertebrate, before being born in small litters.

These incredible species are often harvested for low-value products like pet food, fishmeal, garden fertilizer and industrial lubricants. Groundfish trawlers have either harvested or discarded approximately 1.3-1.4 million individual mud sharks in the last decade alone.4,5

*Calculated using an average weight of 4kg/mud shark

4 Fisheries and Oceans Canada (2024). Groundfish Data Unit. Stock Assessment and Research Division, Fisheries and Oceans Canada. Data provided on August 19, 2024.

5 Fisheries and Oceans Canada (2024). Groundfish Data Unit. Stock Assessment and Research Division, Fisheries and Oceans Canada. Data provided on August 1, 2024.

#3

Deforestation in the Depths: Scraping the Sea Floor

By dragging large weighted nets along the seafloor, bottom trawling is often likened to clear cutting the ocean floor. Bottom trawling causes extensive damage to sea floor habitats, including coral reefs, sponges, seamounts, and other deep-sea benthic ecosystems. While it takes some shallow-water ecosystems several years to recover from bottom trawling damage, deep-water ecosystems, such as seamounts and their long-lived or fragile species, may be irreparably damaged.

Glass sponge reefs are incredibly important to biodiversity and the health of the ocean. They provide habitat for over 120 marine species, creating areas that are three times more biodiverse than surrounding areas. They also “clean” the ocean around them, processing large amounts of carbon and nitrogen, harnessing excess silica and filtering more than 800 times their body volume of water every hour.

Some glass sponge reefs on B.C.’s coast have been aged at 9,000 years old, making them approximately as old as the domestication of cats and the cultivation of wheat and barley. Unfortunately, scientists estimate that by the time the reefs were discovered in 1987, fishing activities like bottom trawling had already destroyed half of them. Some reefs bear the black scars of the “tracks” left behind by bottom trawl gear right over the glass sponge reefs.

Although the annual bottom trawling footprint in B.C. has been reduced in recent years, research shows that 97 per cent of the area along the west coast of Vancouver Island in the depth range of 150 to 1,200 metres has been contacted by bottom-trawl gear in the past.

#4

Acid Oceans and Carbonated Skies: Coughing up more Carbon than Global Aviation

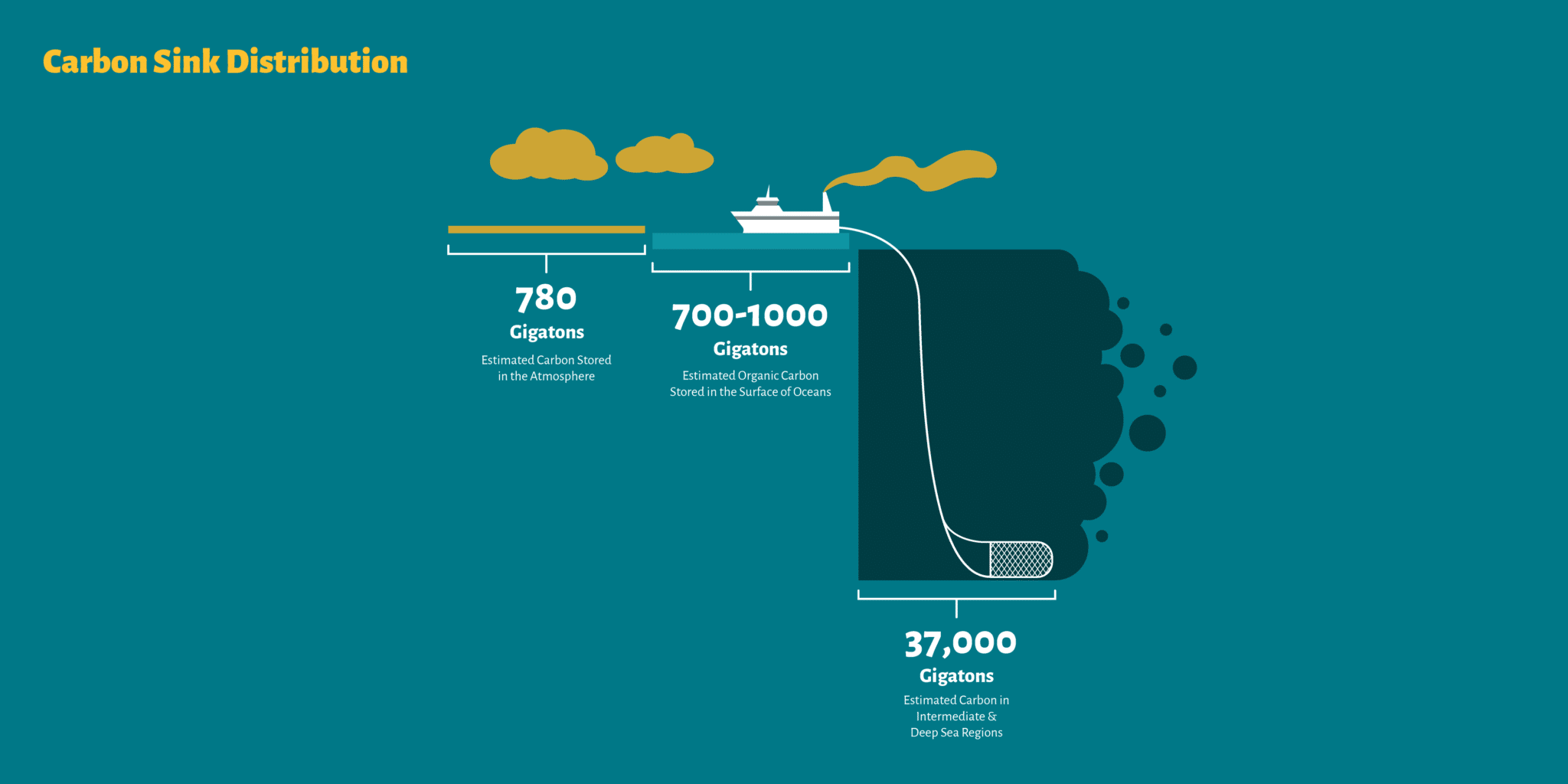

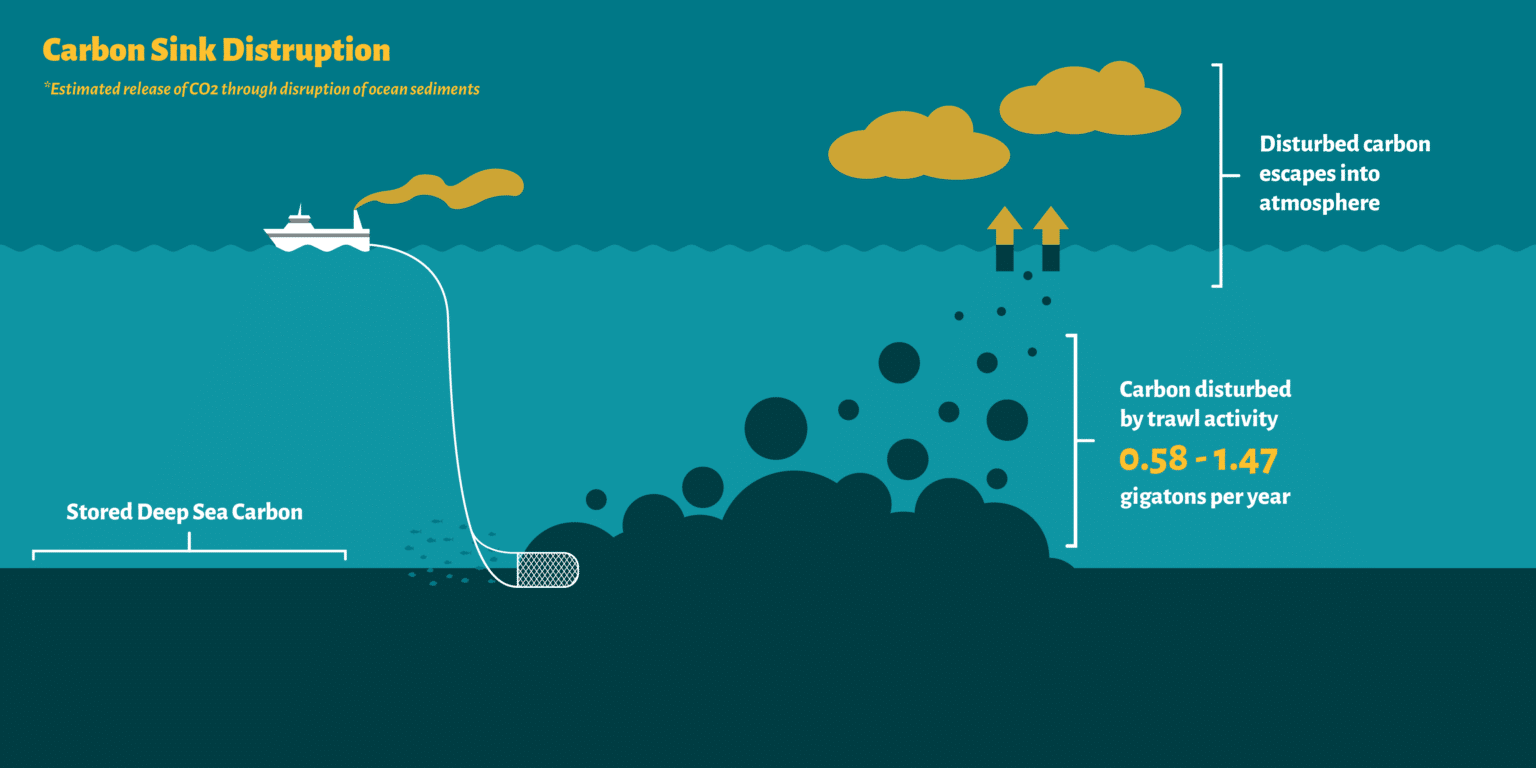

Those fish sticks in your freezer are a climate disaster. Bottom trawling releases as much, or more carbon than the entire aviation industry. The ocean is one of the earth’s largest carbon sinks, storing between 700 and 1000 gigatons of organic carbon with over 37,000 gigatons in intermediate and deep sea regions. For comparison, the atmosphere only holds an estimated 780 gigatons of carbon dioxide (CO2). By disturbing marine sediments, bottom trawling exacerbates the climate crisis by emitting a significant amount of CO2, releasing an estimated 0.58 to 1.47 gigatons each year purely through the disruption of ocean sediments. One gigaton is approximately the weight of 1 billion Volkswagen Beetle cars.

While research indicates that over half the CO2 in the water released from the seabed by trawlers will make it to the atmosphere within nine years, the rest that stays in the water may still wreak additional havoc by contributing to ocean acidification. Ocean acidification can have harmful consequences for marine life, right down to the base of the food web impacting chemical communication, reproduction, and growth. Turning a blind eye to the climate consequences of bottom trawling does not fulfil the letter or the spirit and intent of international agreements signed by Canada to be a climate leader.

#5

Crushing Coastal Communities: Fishing Families are Being Freezed Out

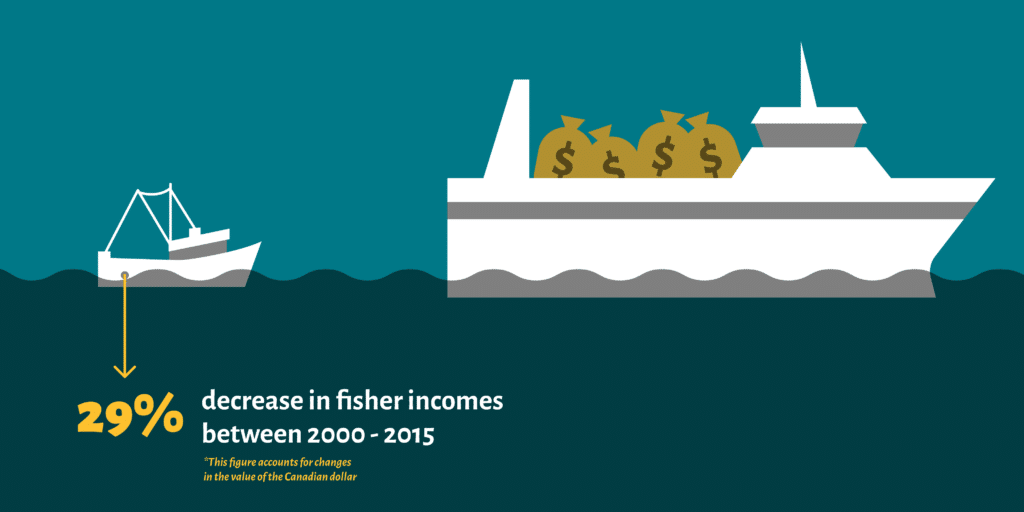

The future of sustainable fisheries is community led, informed by both western science and traditional knowledge. Community-based fisheries should be accessible to coastal communities, in particular First Nation communities. However, this is largely not the case within the groundfish trawl fishery. The trawl fishery in B.C. remains consolidated in the hands of a few wealthy individuals or corporations (including foreign owners) and the economic prospects of fishers have gotten worse. Fishers in B.C. have seen an average 29 per cent decrease in their incomes between 2000 and 2015*

*This figure accounts for changes in the value of the Canadian dollar

Currently, the price of many fishing licences are so high that independent fishers are largely excluded from owning their own licence and quotas. Instead, they are forced to rent it from absentee owners who make more money off of renting their quota than fishing themselves. This is partly because individual transfer quotas (ITQs) can be owned by individuals that are non-active fishers, non-fisher investors, vessels or enterprises, and are transferable through selling, buying, and leasing in an open market. This inequitable allocation of licences and quotas excludes fishers from receiving an adequate share in the benefits of the fishery resources they harvest.

By catching a wide range of other culturally, ecologically and economically important species as bycatch— like salmon, halibut, and herring— trawling causes economic injustice and can negatively impact the long-term sustainability of other fishing sectors, food security, and cultural identification of coastal communities. Within the last decade, over 5,000 tonnes of halibut, approximately 1,107 tonnes of Pacific herring* and at least 140,265 individual salmon (between 2008-2023) has been caught by the trawling industry and discarded as bycatch or waste as a prohibited species.6,7 The indiscriminate nature of this fishery undermines the conservation, stewardship, and enhancement measures put in place to protect these critical species, as well as insults the sacrifices made by coastal communities, First Nations, and other fishers to preserve B.C.’s remaining commercial fish stocks.

Read Dragnetting Coastal Communities to learn more.

* An additional 868 tonnes of “herrings” (Clupeidae) was also caught.

6 Fisheries and Oceans Canada (2024). Groundfish Data Unit. Stock Assessment and Research Division, Fisheries and Oceans Canada. Data provided on May 2, 2024.

7 Lagasse, C.R., Fraser, K.A., Houtman, R., Grundmann, E., Komick, N., O’Brien, M., Braithwaite, E., Cornthwaite, A. M. 2024. Review of Salmon Bycatch in the Pacific Region 2022/23 Groundfish Trawl Fishery and Preliminary Results of an Enhanced Monitoring Program. Can. Manuscr. Rep. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 3273: v + 35 p.

#6

The Perfect Scam: Stick Boats, Stashing Cash and Foreign Ownership

The high degree of concentration of ownership by foreign entities of West Coast fisheries licences and quota, along with the lack of transparency and marginal understanding of who owns or controls those licences and quota by the federal government (DFO), makes the groundfish trawl fishery attractive targets for criminals looking to launder money. One company that has been investing in groundfish, now owns 5.9 million pounds of quota. The director of this company is an overseas investor infamously caught laundering money through casinos and real estate in Vancouver.

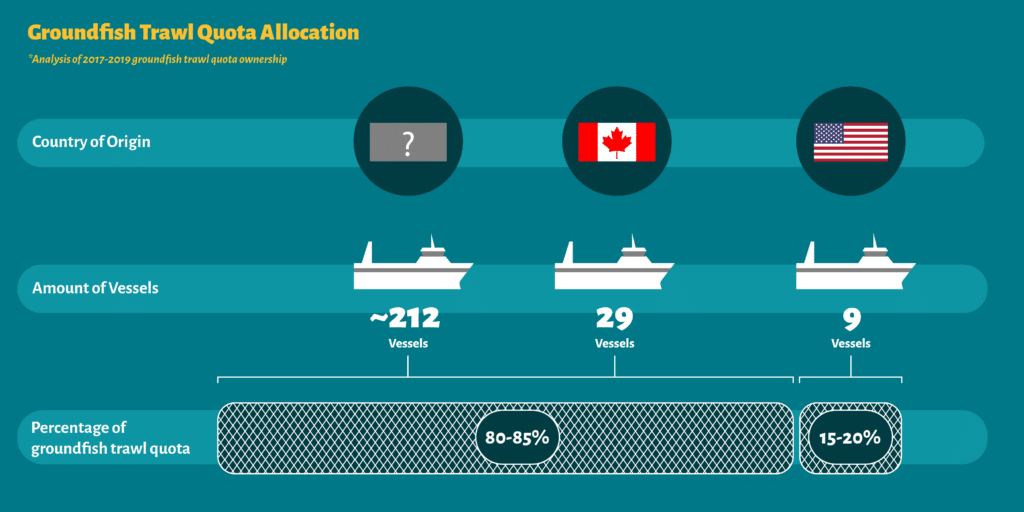

Today, the licence and quota market closely resemble a speculative stock market owned largely by non-fishers. Analysis of quota allocation indicates that only four companies own more than half of the groundfish trawl quota allocation. One of these four groups is foreign owned: an American group that controls 15-20 per cent of the total groundfish trawl quota. According to an analysis performed by DFO, the groundfish trawl fishery has the highest number of licence holders with foreign ownership of all commercial fisheries in British Columbia.

“While the analyses presented in this brief have been carefully checked, the information about beneficial ownership is difficult to verify. This is in itself a disgrace, such information should be required annually by DFO when licenses are renewed. The consequence of this is that I cannot assume responsibility for any related inaccuracy in the analysis. It is possible, however, that the corporate concentration is under-estimated (rather than over-estimated) due to the difficulty of tracing beneficial ownership.”

Dr. Villy Christensen, University of British Columbia (Christensen, V., 2023, pg. 3)

#7

East vs. West: The Concerning Divide in National Fisheries Policies

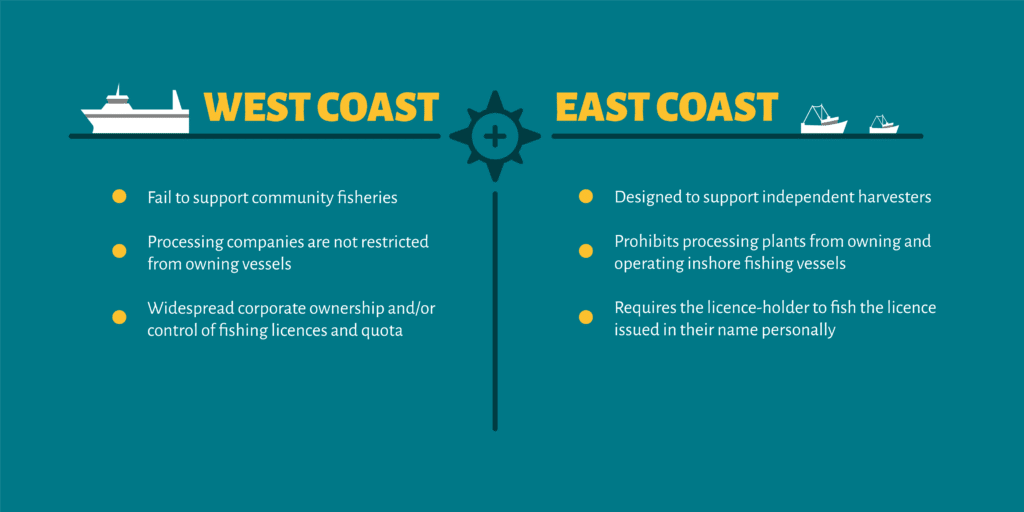

Commercial fishing policies between the east (Atlantic) and west (Pacific) coast of Canada are like night and day. Atlantic policies are designed to support independent harvesters while policies in the Pacific fail to support community fisheries, allowing large corporations dominant control.

Fisheries policy in the Atlantic prohibits processing plants from owning and operating inshore fishing vessels in an effort to protect the interests of the harvesters, particularly with respect to setting shore prices. The owner-operator policy of Atlantic fisheries requires the licence-holder to fish the licence issued in their name personally and typically limits licence holders to one licence per given species. This helps to limit individuals or corporations from owning a large concentration of one fish stock. This policy maximises employment in the fishery and ensures equitable access to the resource.

Conversely, on the Pacific coast, processing companies are not restricted from owning vessels and there is widespread corporate ownership and/or control of fishing licences and quota. Corporate control of licences grants the privilege to harvest public resources (fish stocks) to large companies, not the fishers doing the harvesting.

#8

"Total Lack of Transparency: "Trust us They Say"

Trawl vessels often fish in remote areas far out at sea, where most people don’t go. Effectively monitoring the industry, and gaining public transparency on these monitoring activities is incredibly, and unnecessarily difficult. In a recent performance audit, the Office of the Auditor General of Canada (OAG) uncovered that Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO) is doing a shockingly ineffective job at monitoring Canada’s commercial fishing industry. In the absence of proper monitoring, the audit points out that DFO can not ensure that the fishing industry is sustainable and as a result, our fish stocks may already be overexploited. Indeed, to date, DFO boasts decades-long failure to implement measures to restore the abundance of severely depleted fish stocks.

Over the 2022/23 fishing season, enforcement patrols recorded numerous violations by trawlers which revealed that some vessels were not adhering to the monitoring guidelines and fishing without working cameras, fishing with dirty cameras, fishing with an inadequate number of cameras, and failing to submit fish slips as data. As trawling occurs offshore, far from the eye of fisheries managers, the actual number and magnitude of violations is likely higher than what was observed and reported. Both observers and electronic monitoring services are outsourced to private third-party companies, like Archipelago Marine Research Ltd..

During the review process, it is standard for Archipelago to review only 10-20 percent of the footage captured by electronic monitoring unless a discrepancy is detected. Footage is then typically scrubbed from Archipelago’s system after one month for the groundfish trawl fishery (personal communication, Archipelago, December 13, 2023). However this footage, monitoring the fishing of our common ocean resources on behalf of the government of Canada and therefore its citizens, is not available to the public even through Freedom of Information requests as it is considered the property of Archipelago.

8 Fisheries and Oceans Canada (2024). Groundfish Data Unit. Stock Assessment and Research Division, Fisheries and Oceans Canada. Data provided on May 2, 2024.

#9

The Wild West on Water: Enforcement Goes Easy on Trawlers

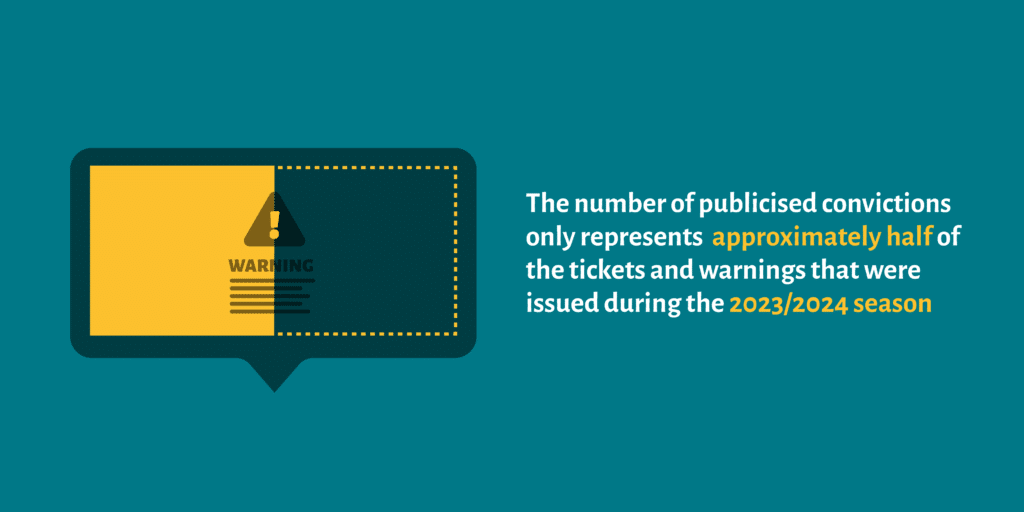

Although mechanisms to aid in the enforcement of the provisions of the Fisheries Act and other relevant regulations and policies exist, they seem to be infrequently used by DFO on the groundfish trawl industry and seem to have little, if any, effect on the deterrence of violations. DFO keeps a public record of convictions under the Fisheries Act in the Pacific region, but this list is only half as long as the list of infractions.

As of March 2024, there have been 19 convictions between October 23, 2023, and February 8, 2024. All 19 convictions have resulted in fines between $500 and $120,000. However, as per Enforcement Reports prepared for the Groundfish Trawl Advisory Committee( GTAC) in 2024⎯DFO’s internal enforcement report outlining non-compliances and Fisheries Act violations⎯the number of publicised convictions only represents approximately half of the tickets and warnings that were issued during the 2023/2024 season. Decision-making rationale on how tickets and warnings are enforced and why ticketable offences do not culminate in criminal charges contrary to the Fisheries Act is not information that is publicly available at this time.

In one case where a crew member was caught shark-finning he was required to perform 25 hours of community service and write an essay about why his behaviour was wrong. A mere slap on the wrist, as seems to be the case for a number of recorded offences, is insufficient to ensure compliance in fisheries as it fails to deter repeat offences and does not promote responsible practices. Furthermore, DFO’s mandate to balance both conservation efforts and the interests of the trawl fishery places them in a potential conflict of interest, as these goals can often be at odds.

#10

Ghost Gear: The Silent Killer

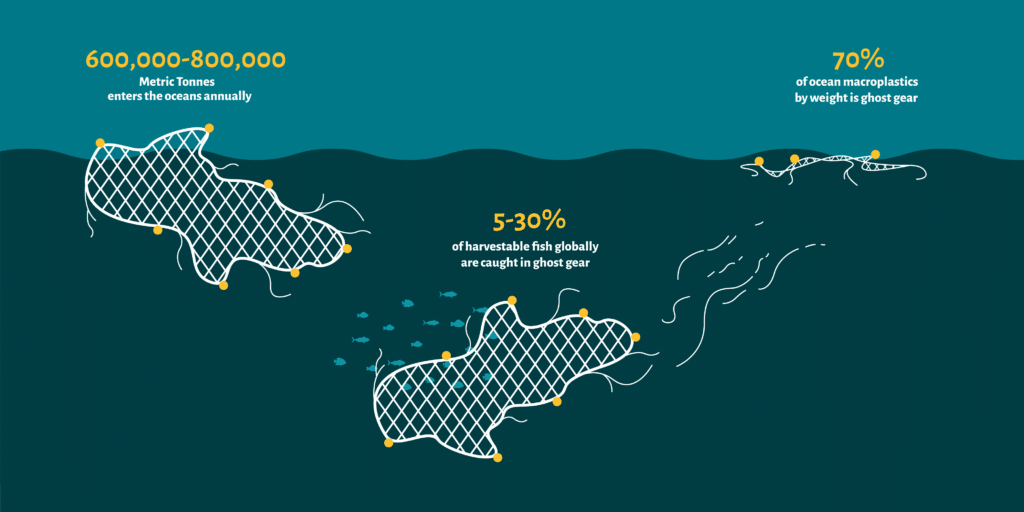

One of the most devastating environmental implications of bottom trawling is caused by ghost gear. These are fishing nets which become detached yet continue to ensnare and kill marine life long after the boats have left. Bottom trawling equipment is especially susceptible to becoming ghost gear due to the immense size and weight of the net once it is full increasing the risk that nets will catch along the bottom. This gear continues to “fish” without anyone harvesting the catch. Every year, 5-30 per cent of harvestable fish globally are caught in ghost gear, a threat to livelihoods and food security. Furthermore, these lost nets contribute to marine plastic pollution. Globally it is estimated that between 600,000-800,000 metric tonnes of ghost gear enter the oceans on an annual basis. That is equivalent to the weight of approximately 8.6 million people living in North America.* This gear will also further break down into microplastics and can have devastating effects on a wide range of marine life. Ghost gear makes up 70 per cent of ocean macro-plastics by weight

* Using the average weight of 180 lbs/person in North America.

What can you do?

Protecting our oceans starts with knowing where your seafood comes from. By being mindful of your choices, you can avoid fish caught by destructive industrial trawlers, whose practices can harm marine ecosystems, deplete fish populations, and disrupt habitats. It’s not just about what’s on your plate; checking pet food labels is important too, as many brands contain fish sourced from these large trawling operations.

Whenever possible, choose to support local, owner-operator fishers who use more sustainable fishing methods. This can help support coastal communities and keep our oceans diverse and thriving – a win-win. Each small, intentional choice helps create a stronger future for our marine life and local fishing families.