The Integrated Fisheries Management Plan (IFMP) for Pacific herring fisheries in 2024/2025 has been released, outlining where and how many herring can be harvested in British Columbia (B.C.) this season. Despite widespread feedback from First Nations, coastal communities, environmental organizations, and independent scientists the department has chosen to disregard expert advice and push forward with unsustainable harvest rates, especially in the Strait of Georgia which contains nearly 40 per cent of the remaining estimated spawning stock biomass in B.C..

The Strait of Georgia is open to several types of herring fisheries, at different times of the year. The Food and Bait and Special Use fisheries typically target herring in the fall and winter before the fish spawn, capturing both resident and migratory populations of herring as they migrate to the coast. These fisheries target herring to use as bait in other fisheries, source aquariums with feed, convert herring into fish meal or fish oil for livestock, aquaculture feed, pet food and fertilizer, and for human consumption. The roe fishery, which is the largest, typically opens in early spring and harvests herring for its eggs before they spawn. These fisheries often operate under a transferable quota system, allowing fishers to trade quotas between fisheries.

The quotas for the 2024/2025 fishing season are as follows:

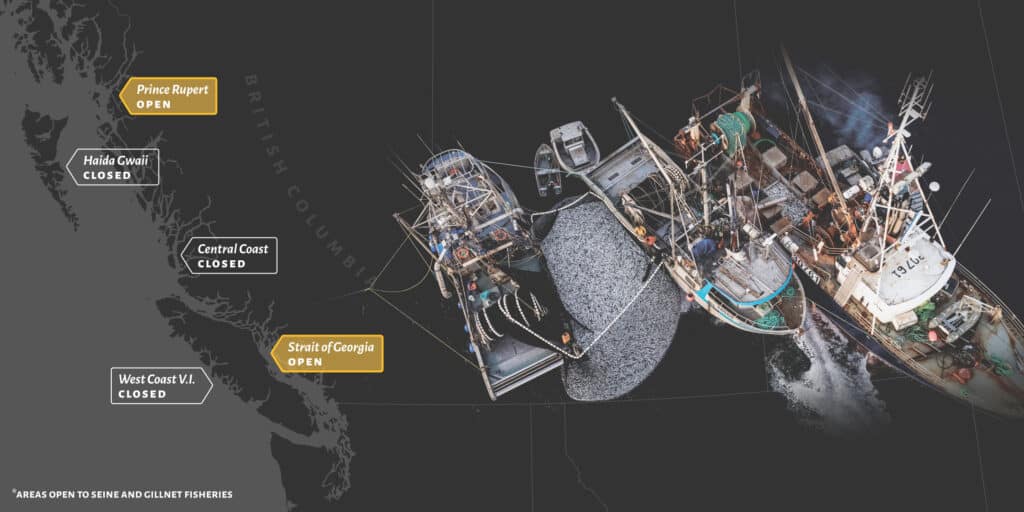

STRAIT OF GEORGIA (SOG):

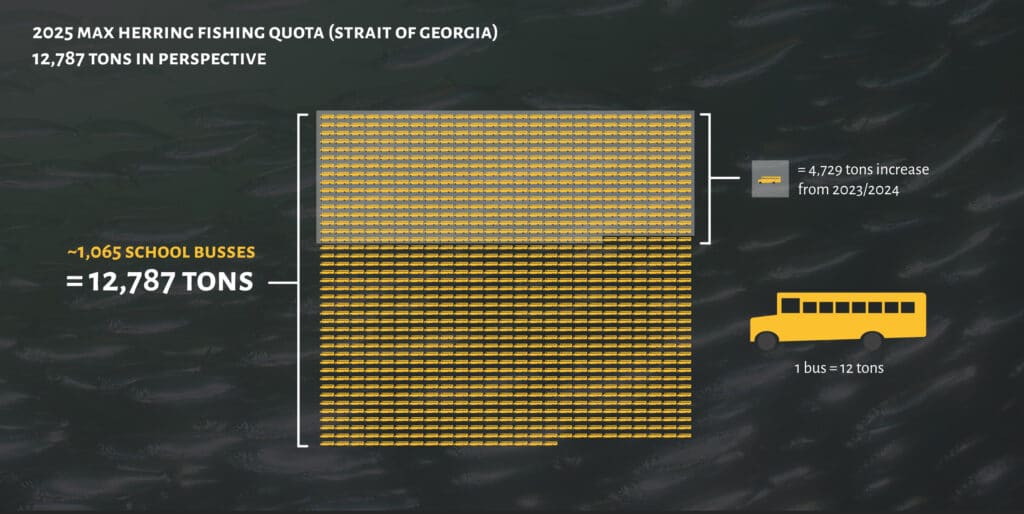

The SOG will be open for Roe (and Food and Bait, Special Use) fisheries, at a 14% harvest rate to a maximum of 12,787 tons.

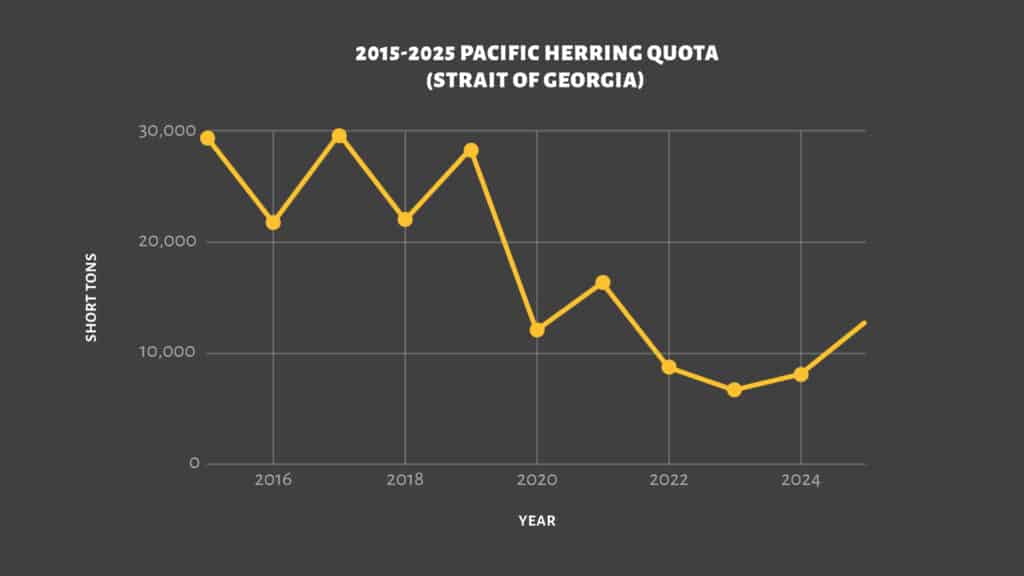

In a significant step backwards, DFO has increased the total allowable catch (TAC) in the Strait of Georgia (SOG) by 4,729 tons from the 2023/2024 fishing season. Herring fishing in the Strait of Georgia has continued uninterrupted since the brief moratorium of the late 1960s.

WEST COAST VANCOUVER ISLAND:

Closed to commercial gillnet and seine harvest. Open to Food Social Ceremonial (FSC), treaty domestic harvest, and commercial Spawn on Kelp opportunities to First Nations.

The west coast of Vancouver Island (WCVI) has not hosted a commercial herring fishery since 2005 after a sharp decline in herring biomass. Although WCVI herring has shown growth and signs of recovery in recent years, Nuu-chah-nulth leaders have continued to express deep concern about the species’ long-term health. As an admirable precautionary measure, First Nations leaders have decided to prohibit commercial gillnet and seine catch within their territories in 2025. However, for the first time in several years, Ha’oom is planning a commercial spawn-on-kelp fishery, revitalizing this economically and culturally significant fishery for the west coast.

CENTRAL COAST:

The central coast will open for a 4.7% harvest rate to a maximum of 900 tons for commercial Spawn on Kelp (SOK) and remain closed to all other commercial herring fishing. This is a 0.7% increase from last year’s 4% harvest rate.

In 2008, the gillnet and seine roe fishery on the central coast was closed. Today, traditional spawn-on-kelp is the only commercial fishery permitted in the region.

PRINCE RUPERT DISTRICT (PRD):

The Prince Rupert District (PRD) will open to a 5% harvest rate for FSC, Spawn on Kelp, and Roe herring to a maximum of 2,624 tons. Total allowable catch for PRD has increased this year by 353 tons.

This district stock has experienced short-term closures and reopenings in recent years as stocks have fluctuated. However, upon re-opening several First Nations have taken to the water to protest, and interfere in gillnet and seine fishing activities within their territories in opposition of the fishery.

HAIDA GWAII:

Closed to commercial harvest.

Commercial herring roe harvests in Haida Gwaii were closed in the early 2000s due to weak stocks. Despite a long-term moratorium, Haida Gwaii herring have not recovered and remain in a low-spawning, low-biomass state. In 2015, the Haida Nation sought and was granted an injunction preventing the Minister of Fisheries and Oceans from opening the commercial herring fishery in spite of struggling stocks.

Herring Management Plan Ignores Public Input

When this latest herring management plan was open for public feedback in the fall of 2024, WSÁNEĆ hereditary chiefs issued a declaration calling for an immediate moratorium on all commercial herring fisheries in the Salish Sea, uniting for the first time in 40 years. The declaration criticises Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO’s) unsustainable quotas and lack of meaningful consultation, and emphasises the ecological importance of herring, which sustain Chinook salmon, Southern Resident killer whales, and other marine species critical to the WSÁNEĆ way of life.

In November, Pacific Wild also made a public call to action, uniting with ten other environmental non-governmental organizations to submit a joint letter founded by science calling for a moratorium on commercial herring fishing in the Strait of Georgia in alignment with the calls of WSÁNEĆ hereditary chiefs. We had hoped the federal government would incorporate this meaningful feedback into its management decisions. Instead, DFO upheld its “talk and fish” approach, ignoring critical recommendations from multiple stakeholders and rightsholders once again.

We are deeply disappointed that DFO has once again chosen to prioritise the needs industry over British Columbians and continues to manage Pacific herring without meaningful understanding or consideration of the role of herring in the ecosystem.

How did we get here

Commercial fisheries began harvesting herring in the late 1800s, primarily to produce fertilizer and fish oil. By the 1960s, decades of intense overfishing had caused herring populations to collapse coastwide. Following a brief closure, commercial fishing resumed in the 1970s with the introduction of the roe fishery, which remains the dominant fishery today. Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO) frequently claims that herring spawning biomass, particularly in the Strait of Georgia, is approaching, or is at, historical highs. However, this assessment is based on an incomplete historical context. The baseline for “healthy stocks” used by DFO relies on population estimates from the 1950s—a period just a decade before the catastrophic collapse of herring stocks coast wide. By then, herring populations had already been severely depleted (up to 99% for all forage fish species, according to one recent study) after 60 years of industrial-scale exploitation.

Today, herring no longer spawn at many of their historical spawning sites along the coast, and where spawning does occur, it is often in much smaller numbers. Even in the Strait of Georgia, considered the last major stronghold for herring on the coast, there is a troubling trend of shrinking spawning areas over time and space. This contraction, both in geographic range and spawn duration over time, raises significant concerns about the long-term health of herring populations.

Since the roe fishery began, additional closures have been enacted as stocks became too depleted to sustain harvests, followed by reopenings whenever DFO determined stocks could handle renewed fishing pressure. Herring harvests in Haida Gwaii were halted in the early 2000s, yet the stocks have not recovered. Shortly afterward, the west coast and central coast stocks were also closed to gillnet and seine roe fisheries. The Prince Rupert District stock has experienced short-term closures and reopenings in recent years, while harvesting in the Strait of Georgia has continued uninterrupted since the brief moratorium of the late 1960s.

Herring management: what is not being considered

Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO) manages Pacific herring using a single-species approach to stock assessment, which focuses narrowly on the impact of fishing on herring populations without adequately considering their broader ecological role. This method treats herring as an isolated resource rather than as a foundational species integral to the health of marine ecosystems. By disregarding herring’s critical role as a food source for a wide range of predators, including salmon, seabirds, and marine mammals, DFO’s approach ignores the cascading effects that overfishing can have on the entire ecosystem.

One glaring oversight in DFO’s management strategy is its failure to account for the return of humpback whales to the Salish Sea and the impact of climate change on herring populations. Humpback whales, which have seen a significant resurgence in recent years, are major predators of herring, but their growing numbers are not reflected in DFO’s stock management. Similarly, the increasing frequency of marine heatwaves and other climate-driven changes may be intensifying natural mortality of herring. By neglecting these factors, DFO underestimates the total pressure on herring populations, potentially leading to overharvesting and ecosystem imbalance.

The dangers of ignoring the interconnected impacts of climate change and predation are evident in the collapse of Atlantic herring stocks in Canada. Decades of single-species management, combined with climate-driven changes in prey availability and habitat conditions, have pushed Atlantic herring populations to critically low levels that ultimately lead to a moratorium on herring fishing in the Gulf of St. Lawrence in 2022. This cautionary tale highlights the risks of failing to take a holistic, ecosystem-based approach to fisheries management. The Atlantic herring collapse has left ecosystems destabilized and fisheries economically depressed, demonstrating the urgent need for a different path forward.

Furthermore, DFO’s management of herring in the Strait of Georgia as a single homogenous stock fails to account for growing independent scientific evidence pointing to the existence of genetically unique sub-stocks of resident and migratory herring. Treating these distinct populations as a single unit ignores critical differences in their life cycles, habitats, and vulnerabilities, leading to a one-size-fits-all approach to harvest quotas and stock assessments. This lack of distinction risks disproportionately depleting resident herring, which remain in the Strait year-round and are particularly vital to the local ecosystem as a consistent food source for predators like Chinook salmon, which in turn feed the critically endangered Southern Resident killer whale population. By not addressing these genetic and behavioral distinctions, DFO undermines the resilience of herring populations and the broader ecosystem, leaving these foundational fish more susceptible to overfishing and environmental changes. Proper management must recognize and protect the unique sub-stocks to ensure the long-term sustainability of herring in the Strait of Georgia.

If DFO continues to manage Pacific herring without considering their pivotal ecological role and the broader environmental context, the Salish Sea may face similar consequences to what occurred with Atlantic herring. An ecosystem-based approach, which factors in climate impacts, predation by recovering species like humpback whales, and the cascading effects of herring decline, is essential to ensure the sustainability of not only herring stocks but also the species and communities that depend on them. Without this shift, the continued prioritisation of short-term industry gains over long-term ecological health risks the collapse of yet another critical species in Canada’s waters.

Canada has begun taking the preliminary steps toward implementing an Ecosystem Approach to Fisheries Management (EAFM), aiming to consider the interconnectedness of species, habitats, and environmental factors in fisheries decisions. However, EAFM is in its infancy and fully adopting this framework is likely years, if not decades away. In the meantime, DFO continues its “talk and fish” approach, managing herring with outdated single-species stock assessment strategies that only address a fraction of the picture.

Herring, as a critical foundational species threatened by climate change and intensifying predation, cannot afford to wait for these gradual changes. To prevent further decline, herring must be managed with an ecosystem-based lens now. As a precautionary measure, a temporary moratorium should be implemented to protect herring populations and let them recover to near-historic levels while there are still favorable climate conditions to do so. The risk of continuing on the current path is simply too great.