Table of Contents

culture

#1

Herring are culturally vital to coastal cultures, and have been for thousands of years

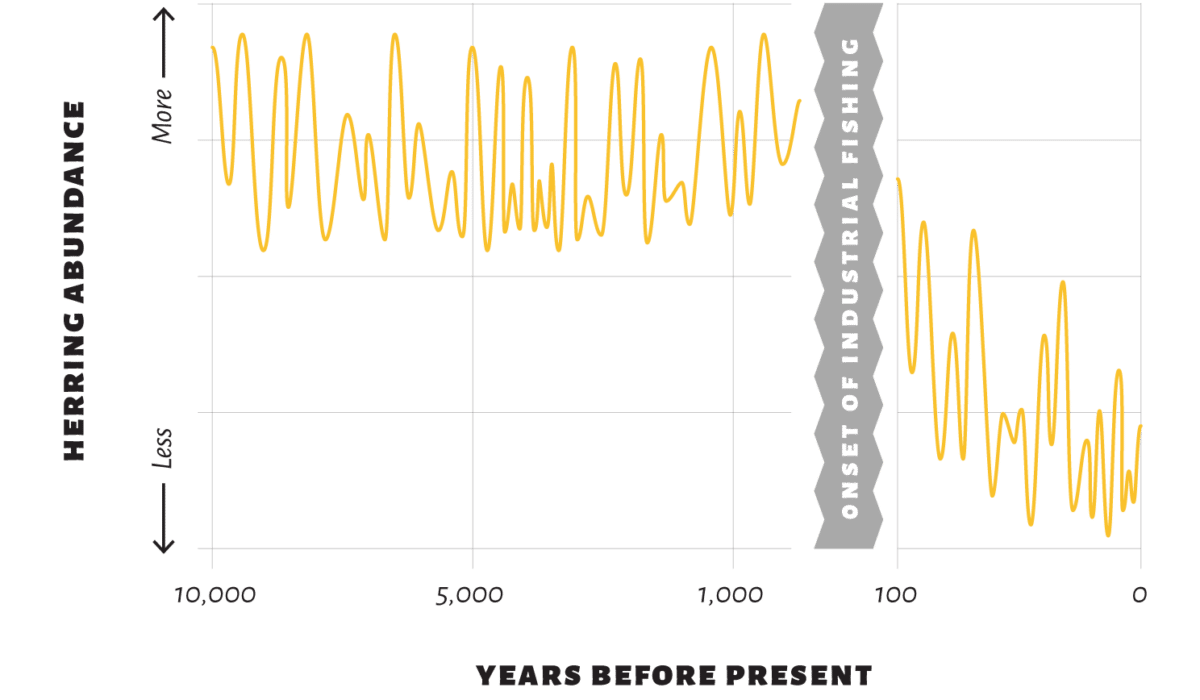

First Nations fished Pacific herring sustainably for thousands of years before industrial fishing. Archaeological records dating up to 10,700 years ago show that herring were much more abundant and widespread than they are today. In 171 archaeological sites stretching from Puget Sound into southeastern Alaska, herring bones made up almost half of all fish bones, on average, and were found at 99% of sites. Additionally, herring was the most numerous fish found in 56% of archeological sites indicating that In some parts of the B.C. coast, herring may have been a more important food source than Pacific salmon at some points of the year. Now only a handful of Nations are able to fish for herring within their territory in the Strait of Georgia.

Source: McKechnie et al. 2014.

ecology

#2

Herring feed the coast

Herring play a key role in the coastal ecosystem, transferring energy throughout the food web from plankton to bigger animals, like salmon, seabirds, whales, and humans too. Herring are an important food for fish like Chinook and coho salmon, lingcod, Pacific halibut, and Pacific hake. Marine mammals also rely on herring and herring roe, such as humpback whales, gray whales, Pacific white-sided dolphins, porpoises, sea lions, and seals. Millions of seabirds, like cormorants, murres and scoters, feed on spawning adults and eggs. Surf scoters time their migration to summer nesting grounds to coincide with the herring spawning event. Bears and wolves travel to the tideline during and after the spawn to gorge themselves on herring eggs. Even plants that grow on beaches near herring spawning sites contain nutrients that come from herring. As herring become smaller and less common over time, there is less food to go around. A complete collapse of herring populations would cause ecosystem-wide changes.

ecology

#3

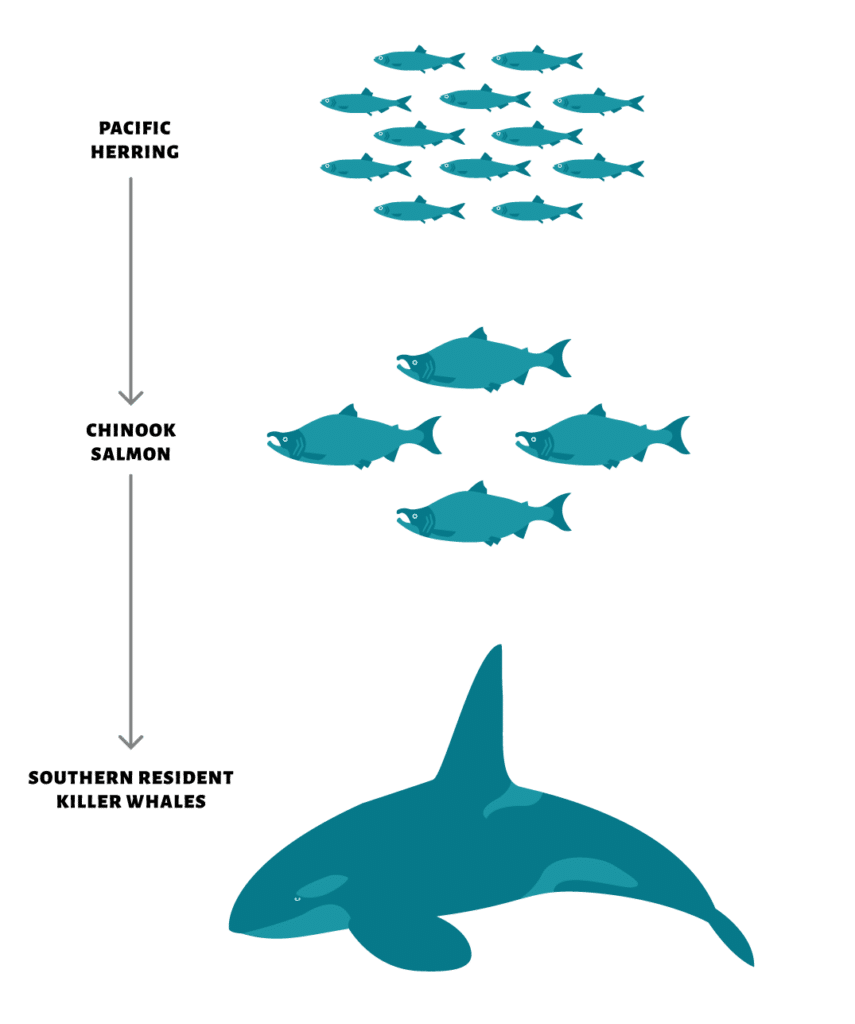

Herring are essential food for many endangered species

The role of herring in the coastal ecosystem and food web is unparalleled. Their abundance and seasonal reproduction provides foraging opportunities for hundreds of ecologically, economically and culturally important species. The survival of threatened and endangered species, like Chinook salmon and Southern Resident killer whales, is directly linked to herring. Healthy herring populations are critical for Chinook survival, which in turn feed resident killer whales. Research indicates that access to Pacific herring is important to the growth and survival of juvenile Chinook. Pacific herring also contribute approximately 62% to the diet of adult Chinook salmon in offshore areas, like La Pérouse Bank, which is critical habitat for Southern Resident killer whales. Chinook salmon are the primary food source for the critically endangered Southern Resident killer whales, making up to 90% of their diet in critical habitat areas during the summer months.

ecology

#4

Herring are disappearing from their historic range

Today, herring are absent from large expanses of their historic range across B.C. as populations have been fished to oblivion. In the Strait of Georgia (SOG), herring spawn has been disappearing in a generally south-to-north direction. For decades, Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO) has been managing herring in the SOG as one homogenous unit rather than separating them into distinct resident (local) and migratory populations despite years of evidence that they exist. When small local stocks are fished as part of a larger-scale quota, they are at risk of collapsing. In the SOG, many of these small local stocks were likely extirpated after the massive stock collapse in the 1960s. Today, there are increasingly smaller areas where spawning still takes place. Even the pockets within the Strait of Georgia that have seen consistently high spawning activity, are at risk of shrinking and growing fewer and farther between. The drivers of the disappearing spawning area in the SOG remain unidentified and unmanaged by DFO. Under our current fishery management practices the genetic diversity in Pacific herring may be irrevocably reduced, thereby reducing the ability of species to adapt to future environmental conditions and climate change.

Strait of Georgia Surface Spawn 1960’s-2020’s

ecology

#5

The commercial net and seine fishery catches herring right before spawning

Each spring, schools of herring flood into the bays and inlets of the Salish Sea to spawn. Each female herring lays thousands of sticky eggs on kelp and eelgrass growing in shallow water. Male herring release milt into the water, which fertilizes the eggs and turns the waters along the coast milky white. Unlike Pacific salmon, herring don’t die after spawning. Herring return to the same place to spawn, year after year. On average, this annual cycle occurs five to seven times in their lifetime, but some herring may spawn up to nine times in their lives. Young herring spend a few years in the Salish Sea, where they are food for salmon, Pacific cod, lingcod, and rockfish species. When they become mature at three- or four-years-old, young herring join the migration to offshore feeding grounds. The commercial seine and net fishery catches herring right before spawning, interrupting the production of billions of fertilized eggs, year after year.

ecology

#6

Young herring rely on older herring for knowledge

Just as salmon return to their natal streams to spawn, herring typically return to the same spawning area in which they were born. But unlike salmon, many generations of herring spawn together. Older fish hold important hereditary knowledge, like where to spawn, and they pass this knowledge down to younger fish. This social learning transmits migratory knowledge between generations. Because the herring fishery catches the largest fish, which are the oldest, it removes important knowledge from the population. Some experts say this loss of knowledge explains why herring no longer spawn in many old spawning locations—they have forgotten where to go.

Economy

#7

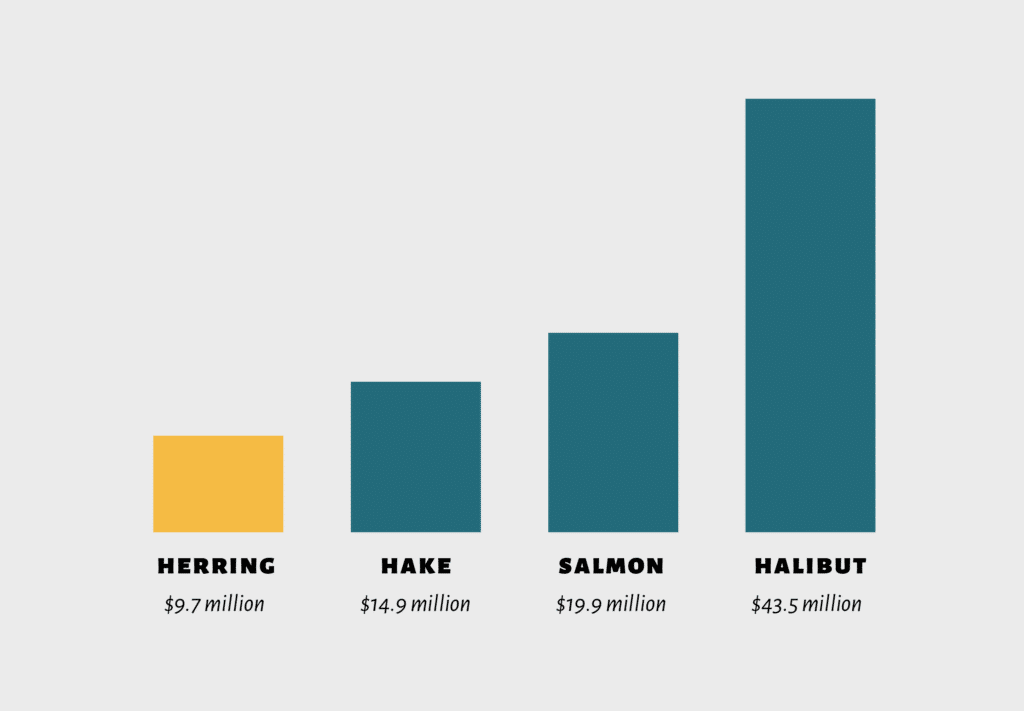

Herring are worth more in the water

Herring contribute more to B.C.’s economy by feeding other species than by being caught and processed. Many of the fish species that eat herring support lucrative commercial and sport fisheries. In 2021, B.C. commercial fisheries for salmon, halibut, and hake were worth around $19.9 million, $43.5 million, and $14.9 million in landed value, respectively. In the same year, the sum landed value of the commercial herring fisheries (spawn on kelp, herring roe, and food and bait) was just under $9.7 million, making up only around 2% of the total value of commercial fishery in B.C.. Marine-based tourism such as recreational fishing and whale watching generate more than $5 billion to B.C.’s economy each year. The whale and salmon populations that rely on herring, like Chinook salmon, humpbacks and killer whales, draw hundreds of thousands of tourists to B.C. annually. Herring are most valuable to B.C. as the foundation of the coastal ecosystem. Better management of herring populations is an investment in B.C.’s economic future.

Economy

#8

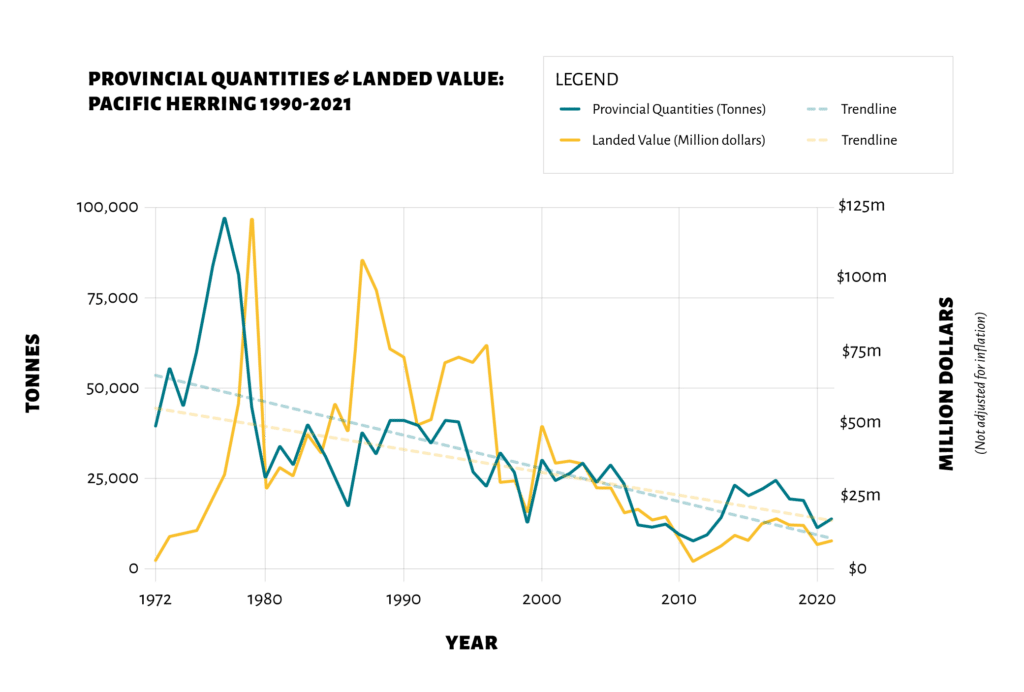

The herring fishery is in decline

The herring fishery is worth a fraction of what it was in the past — both the landed, wholesale value and exports of herring is on a downward trajectory. For example, in 1990, the average landed value of Pacific herring per kilogram was around $1.78, far greater than the average of around $0.71 per kilogram in 2021. As the overall value of the fishery declines, each boat typically must fish multiple licences to make enough money to offset the costs of fishing. Furthermore, a large amount of income from the fishery goes to large corporations like Canfisco rather than independent fishers and fishing families. We are currently managing herring to economic and biological decimation. With herring worth so much more in the water, it makes little sense to risk the collapse of the Strait of Georgia population for a fading fishery.

Source: Morley. 2016. Testimony to the Standing Committee on Fisheries and Oceans, Canadian Parliament.

Source: Fisheries and Oceans Canada. 1990-2021.

Management

#9

DFO is using the wrong population baseline

The B.C. commercial herring fishery began in 1876 and caught huge quantities of herring in the first half of the 20th century. By 1910, government officials noted that herring were less common in areas where they had been abundant. In 1962, the B.C. catch peaked at 237,600 tons, nearly three times the entire spawning biomass of herring in the Strait of Georgia today (estimated at 80,882 tons in 2024). In 1967, populations collapsed coastwide after decades of commercial fishing. The current management system for herring is based on an incomplete picture of B.C. herring populations, because it uses population estimates from the 1950’s as their baseline for healthy stocks, even though these populations were already depleted by 60 years of industrial fishing at that time. New research indicates that forage fish populations, including herring, decreased by as much as 99% since European colonization. Using 1951 data as a population baseline is misleading. It conceals the declines caused by the early fishery and limits the scope of recovery for B.C. herring populations.

Management

#10

The majority of herring populations have crashed

The Strait of Georgia (SOG) is home to the last large herring population in B.C.. For over two decades, herring fisheries off Haida Gwaii, the Central Coast, and the West Coast of Vancouver Island have been closed many times under DFO management, because the populations were too small to support a fishery. Despite years of little fishing, these populations have been slow to show signs of meaningful recovery. The Prince Rupert herring fishery has also been closed in recent years. Today, fishing is open but there are limited commercial opportunities in the region. The factors that affect herring populations are complex. Ocean conditions, food availability, predators, and fishing can all contribute to low herring numbers. However, DFO management has not modeled herring populations accurately as well. In 2018, a DFO review found that management models were overpredicting herring in the SOG for years. As a result, DFO’s internal team recommended a reduction of harvest rate from 20 to 10 per cent as the most effective way to mitigate stock assessment errors. We cannot risk the herring population in the SOG for a fishery that is known for unreliable models which have already contributed to collapse of the majority of populations in B.C..

Management

#11

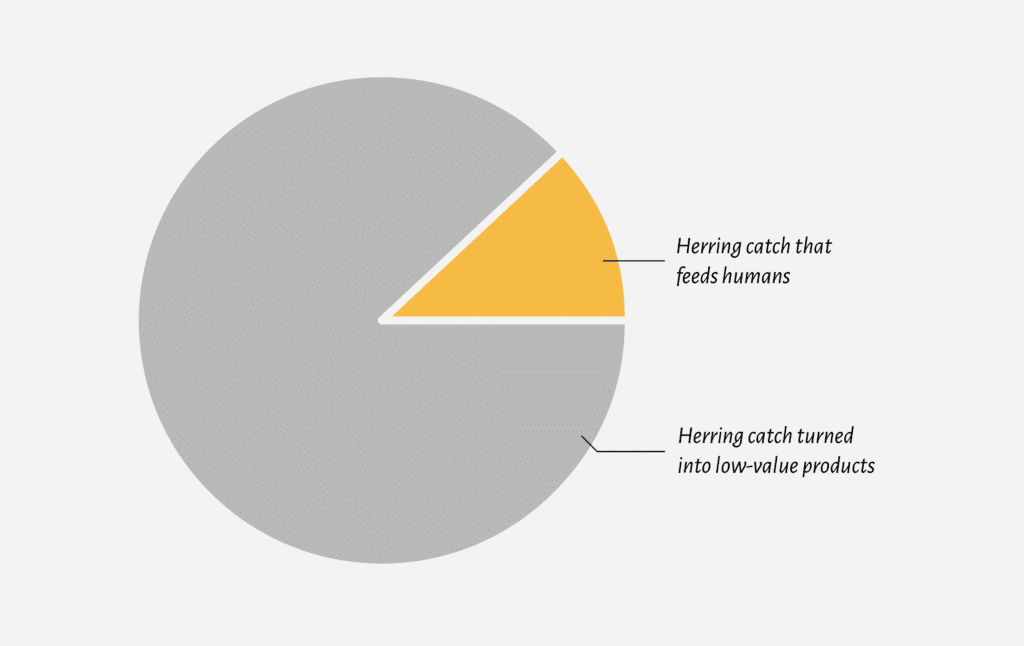

Only 12% of the catch feeds humans —in Japan

In the roe fishery, adult herring are captured just before spawning, and the eggs (roe) are removed from the female fish. After processing to remove the roe from female herring, the carcasses of male and female herring are largely sold to reduction companies. The roe, which is only 12% of the catch on average, is mostly sold in Japan as a luxury food. The remaining 88% of the catch, the carcasses from the male and female herring, are ground up and turned into low-value products like pet food, fertilizer and aquaculture feed for farmed salmon in B.C.’s open-net pen operations along the coast.

Source: Victoria Postlethwaite, DFO Regional Herring Officer. December 12, 2018 (personal communication by email)

Source: Cashion, T. 2019.

Management

#12

Pacific herring already face many other unmanaged industrial threats

Pacific herring face largely unmanaged threats and pressures from other industries in B.C. such as bycatch by trawlers, toxic exposure from ship breaking, and displacement by open-net salmon farms. In 2022, nearly 500 tons of Pacific herring was caught as bycatch by commercial groundfish trawlers in B.C. As status-quo fisheries monitoring programs are often ineffective, the bycatch may be much higher in reality. Ship breaking in Baynes Sound is leaching heavy metals into the environment, exposing spawning adults and juvenile herring to heavy metal toxicity. At its highest, the discharge of copper, lead, zinc and cadmium at a shipbreaking worksite was 3990%, 1240%, 3720% and 23.5% higher than the safe threshold dictated by the B.C. Water Quality Guidelines, respectively. In forage fish, heavy metal toxicity can cause acute die offs or reduced growth, reduced reproduction, and irregular larval (early life) development at chronic low level exposures. According to Traditional Ecological Knowledge, open-net salmon farms displace herring from traditional spawning grounds. In addition, herring are often caught and killed as bycatch within open-net pens from interactions with delousing equipment or as prey to farmed salmon.

Management

#13

The Food and Bait fishery adds further pressure on herring populations

In addition to pressure from the commercial roe fishery, herring are also captured in the Food and Bait and Special Use fishery in the Strait of Georgia. The Food and Bait fishery typically catches herring between November and January, prior to the roe herring season. Herring caught in Food and Bait fisheries in the Strait of Georgia are largely shipped to Australia, where most are fed to tuna in ocean ranches. Alternatively herring are used to feed captive animals in aquaria. DFO states that the Food and Bait fishery focuses on migratory stocks; however, there is sufficient evidence to suggest that many regions are home to both local and migratory populations of herring that are harvested as a homogenous unit. This crucial information has remained under-researched and unmentioned in management plans despite the acknowledgement of the existence of local, non-migratory herring populations as early as 1934. Independent research indicates the potential conservation risks of ignoring sub-stock level dynamics in Pacific herring. When small local stocks are fished as part of a larger-scale quota, they may collapse. In B.C., many of these small local stocks have already been extirpated after the massive stock collapse in the 1960s, and now many coastal communities which historically had spawning activity, no longer do.

Management

#14

Fisheries closures are an actionable item under our control

Changes in natural mortality are an important driver of population dynamics of Pacific herring. In recent years, mortality pressures (such as the effects of climate change and natural predation) for herring has been increasing exponentially. In the Salish Sea, projections indicate higher air and water temperatures as global climate change progresses. As sea surface temperatures rise, juvenile herring in early life stages are likely to be profoundly affected as temperature affects metabolism. As a single stressor, elevated temperature has been shown to generate greater embryo heart rates and mortality, lower hatching success, and shorter larval lengths. Increased temperatures can also result in the development of abnormalities in the pectoral fins and spinal cords. These abnormalities likely affect the growth and survival of later life stages through diminished swimming performance, leading to greater mortality from an inability to capture prey or avoid predators. In a time of unprecedented natural threats threatening the recovery of Pacific herring, fisheries closures are a controlled, actionable item DFO can take to mitigate known threats.

What can you do?

The most effective way to help Pacific herring is to write to your local representatives and federal Fisheries Minister, Diane Lebouthillier, telling them that you support an immediate moratorium and movement towards an ecosystem-based approach to management of the herring fishery. This would allow populations to come back to historic levels. It’s time for Fisheries and Oceans Canada to protect this #BIGLittleFish for generations to come.