In a recent performance audit, the Office of the Auditor General of Canada (OAG) uncovered that Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO) is doing a shockingly ineffective job at monitoring Canada’s commercial fishing industry. In the absence of proper monitoring, the audit points out that DFO can not ensure that the fishing industry is sustainable and as a result, our fish stocks may already be overexploited.

This affects all of us. As a country with the longest coastline in the world, Canada has a legacy of historic overfishing. To date, DFO boasts decades-long failure to implement measures to restore the abundance of severely depleted stocks. In 2023, there are no healthy forage fish populations in either Atlantic or Pacific regions and many populations of Pacific salmon are famously failing to thrive. Despite growing urgency and commitments from DFO to act, fisheries management in Canada continues to be plagued by persistent mismanagement, overfishing, and a failure to rebuild depleted populations.

As of 2022, there were 156 federally managed key commercial marine fish stocks on Canada’s east and west coasts and in the Arctic. None were being assessed to the full extent of Fisheries and Oceans Canada’s Fishery Monitoring Policy to determine whether the level of monitoring was adequate.

Report 9, p. iv

The data and information collected by fisheries monitoring efforts is used to inform management decisions, support scientific assessments of fish stock health, and help set seasonal quotas to ensure the long-term sustainable use of fish populations through proper resource allocation. In the absence of this data DFO is blindly making fisheries management decisions and issuing quotas in the dark. Auditors concluded that the fish catch information from at-sea and dockside monitoring programs are often not dependable sources of data and do not form a solid basis that DFO can rely on for decision making. However, DFO continues to make decisions about targets and quotas with significantly inadequate data at the expense of fish stocks, marine ecosystems, and Canadians.

To date, at-sea monitoring is often simply not done, or when it is done the target coverage (intended percent of fishing time DFO requires a given fishery to be observed) is not met. The target coverage can vary substantially from as little as 2.5% to 100% in commercial fisheries. Observer coverage is only required for some types of fishing licences in Canada. Of the 101 fish stocks subject to at-sea observation, the audit uncovered significant problems with at-sea observation coverage for 75 of them.

The Office of the Auditor General of Canada serves Parliament by providing it with objective, fact-based information and expert advice on government programs and activities, gathered through audits.

Office of the Auditor General of Canada

Performance audits are part of ensuring that the public service is acting ethically and effectively and that the government is accountable to Parliament and Canadians. By law, DFO has to give data to the OAG for review; however, even auditors have found it extremely challenging to obtain data from the department or, worse, the data requested simply does not exist (D. Normand, personal communication, November 28, 2023).

DFO was last audited by the OAG in 2016. This previous audit found that key information needed to manage Canada’s fish stocks sustainably was missing. The 2016 audit found that DFO was failing to:

- carry out all of the scientific surveys it had planned, and

- have adequate controls to ensure that it gathered reliable and up-to-date data from third-party fisheries observers.

As a result of their inability to collect adequate data, the audit concluded that DFO was unable to assign all its major stocks into their appropriate classification: healthy, cautious, or critical.

Seven years later, DFO has yet to deliver on most of the corrective measures that it committed to in its responses to the recommendations from the 2016 audit. DFO’s “talk and fish” approach to conservation and fisheries management leaves Canada’s fish stocks vulnerable to collapse, as demonstrated by the tragic collapse of the Atlantic northwest cod fishery in the 1990s. The 2023 audit focuses on the ability of DFO to monitor marine fisheries catch. An additional audit assessing the department’s ability to carry out scientific surveys is expected in the near future (D. Normand, personal communication, November 28, 2023).

The department did not fully deliver on its 2016 commitment to modernize its fisheries information management systems by 2020, including creating an integrated system for all regions.

Report 9, p. iv

As of 2022, there were 156 federally managed key commercial marine fish stocks in Canadian waters. The OAG’s 2023 audit concluded that none of Canada’s federally managed key commercial marine fish stocks are being assessed to the full extent of DFO’s Fishery Monitoring Policy to determine whether the level of monitoring is adequate for Canada’s commercial stocks.

Proper monitoring within the commercial fishing industry is essential. DFO uses a variety of monitoring tools including:

- fishing logbooks (paper or electronic records kept by harvesters of their fishing activities),

- electronic devices (including cameras on board vessels).

- at-sea observers and

- dockside observers (hired by independent third-party companies, who verify catch data and also provide the department with information on biological characteristics)

The department still did not ensure that catch data collected by third-party observers was dependable and timely.

Report 9, p. iv

In the case of the at-sea and dockside observer programs, the OAG’s 2023 audit uncovered alarming failures in data collection and quality. Not only was DFO not able to provide the data necessary to support its own monitoring requirements, the data that they did supply to the audit showed that 80% of the time at-sea and 60% of the time dockside, coverage targets were not met or the department could not provide evidence that targets were met (in cases they reported that it had met coverage targets).

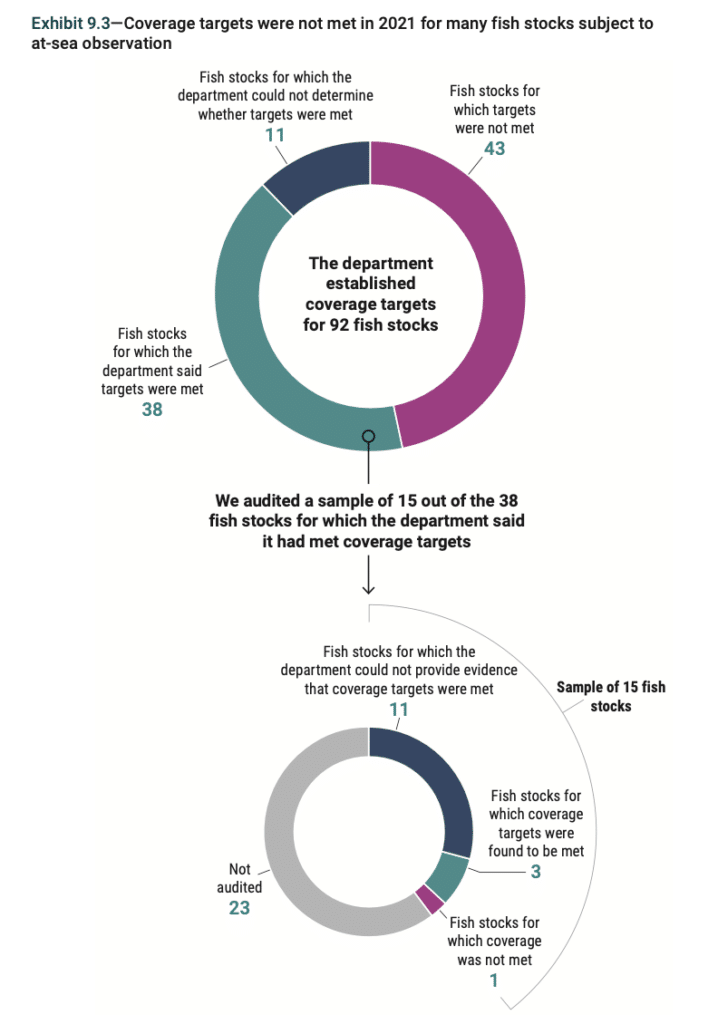

(Exhibit 9.3)

Coverage targets were not met by at-sea observers for many fish stocks. Of 92 stocks, DFO claimed to meet their coverage targets for only 38 stocks (41%). The OAG audited a sample of 15 stocks within the 38 that DFO claimed to meet coverage targets. Of the audited stocks, only 3 out of 15 (20%) actually met coverage targets. 80% of the time DFO claimed to meet coverage targets, they could not provide the data to prove that claim, or failed to meet coverage targets all together.

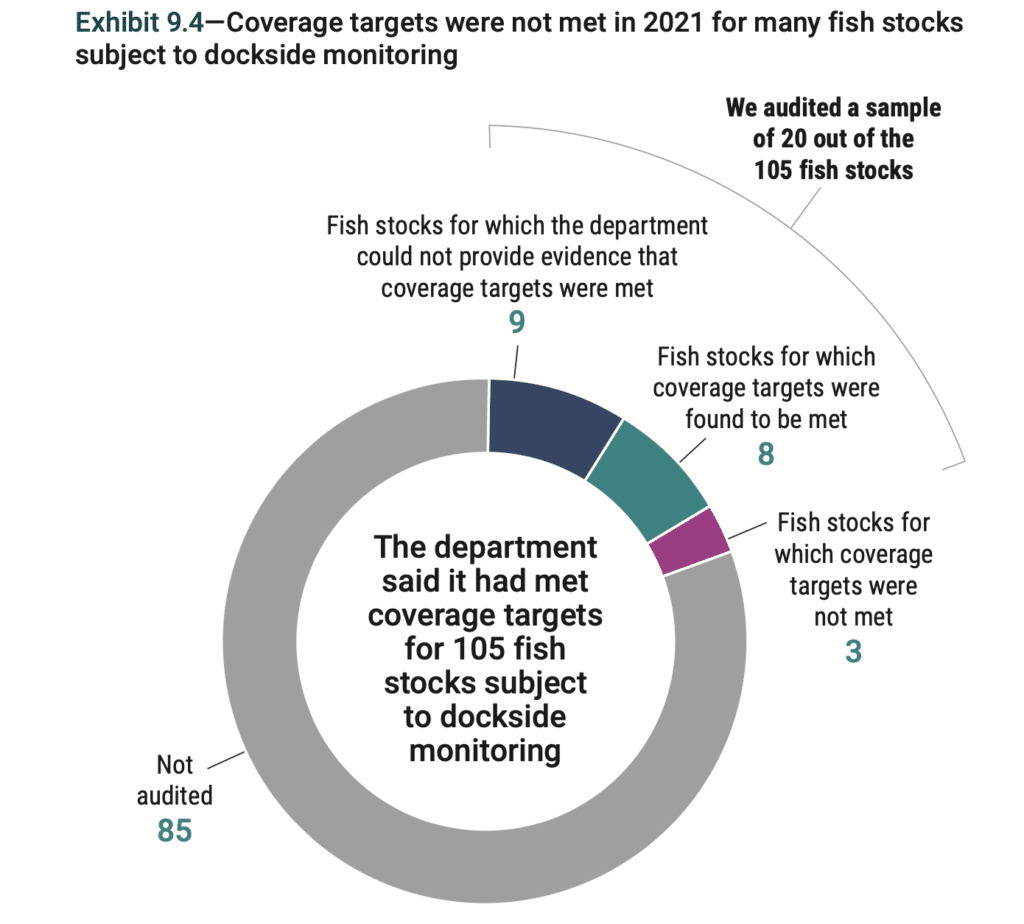

(Exhibit 9.4)

Coverage targets were not met by dockside observers for many fish stocks. DFO claimed to meet coverage targets for 105 stocks subject to dockside monitoring. The OAG audited 20 of the stocks and found that only 8 actually met coverage targets. 60% of the time DFO claimed to meet coverage targets for dockside monitoring, they could not provide the data to prove that claim, or failed to meet coverage targets all together when auditors checked the claim.

In Deep Trouble: Fisheries Failure Case Study

The findings of the 2023 report by the OAG is disappointing; however, they are unsurprising. Taking a closer look at the Pacific groundfish fishery (mid-water and bottom trawl) provides one case study of why the OAG came up with such dismal results in their audit of commercial fisheries in Canada.

The Pacific groundfish trawl fishery is subject to 100% catch monitoring coverage. Prior to 2020, trawl vessels were required to have one independent at-sea observer on board to monitor and verify catch. In lieu of Covid-19, at-sea observers were replaced by electronic monitoring through the use of cameras. Both observers and electronic monitoring services are outsourced to private third-party companies, like Archipelago. During the review process, it is standard to review only 10% of the footage captured by electronic monitoring. Footage is then typically scrubbed from Archipelago’s system after 1 month for the groundfish trawl fishery (personal communication, Archipelago, December 13, 2023). Though monitoring the harvest of a public resource (fish), this video footage is generally considered proprietary and cannot be accessed by the public.

Our team reviewed an enforcement report for the Groundfish Trawl Advisory Committee (GTAC) covering the start of the 2022/23 fishing season until November 7, 2022. We were shocked at the number and gravity of violations documented. Over the 2022/23 fishing season, enforcement patrols were only in the field for two two-week long patrols and two aerial missions with the Fisheries Aerial Surveillance Enforcement (FASE) program. These patrols were forced to do part of the operation from the dock rather than at-sea during active fishing due to weather. There were 34 active vessels fishing during the four-week window, but only 12 (less than half of the total ships) were inspected.

In regards to monitoring, the violations documented in the report read as follows:

- One vessel completed an entire trip without a camera working;

- There were two incidents of dirty cameras;

- There were two vessels that were fishing the west coast with only two cameras when they required three;

- Only eight of 34 active vessels submitted fish slips for the season;

- In May 2022, a trawl vessel master was fined for not completing fish slips for four years;

- 28 occurrence reports that observers have been unable to perform hold checks as vessels have left the dock;

What are fish slips?

Harvesters use fish slips to record and report information about fishing catch and effort. We need this information to assess fish stocks and manage fisheries. Fishers are required to submit this information to DFO under federal regulations, as well as some species licence conditions.

What is a hold check?

Hold checks are typically performed by observers for factory freezer trawlers to monitor the amount of frozen fish product on board. Hold checks can be conducted by counting individual boxes or the hold capacity can be determined through volumetric calculations.

For a fishery that is subject to 100% catch monitoring and boasts being recognized globally for their fisheries practices, these findings are abysmal.

Other, non-monitoring related infractions documented in the report include:

- Five occurrence reports of vessels fishing in a closed area (one vessel in USA waters, one vessel in the Swiftsure closure, two vessels in the Hecate Strait Glass Sponge Reef MPA, and two vessels outside the trawl footprint);

- 55 occurrence reports for vessels discarding rockfish;

- Of twelve trawl vessels inspected, seven vessels had crew members without fisher registration cards (FRC);

- 343 occurrences of prohibited species landed;

- One vessel completed two trips without a valid 2022_2023 trawl license;

- Two reports of feeding marine mammals;

- Two vessels completed trips without measuring grids (used to determine if fish are large enough to retain) while others are not measuring grids properly;

- Four occurrence reports for processing fish at sea, which is not allowed;

- 265 occurrence reports for undersized sablefish and lingcod landed;

- and vessel masters are not reporting marine mammal and shark encounters in their logbooks.

The report also contained a strong reminder of the new section created in the Fisheries Act in 2019 prohibiting shark finning.

In commercial fisheries, like the groundfish trawl fishery, fishing activity occurs far offshore. Out of sight and out of mind of the public, and more often than not, out of the eye of enforcement it is hard to know exactly what is occuring aboard these trawl vessels. Honest, accurate and effective monitoring is the only way to track what is happening offshore. This is not being done. And that spells #DeepTrouble for B.C.’s commercial fish stocks.

Thank you to the representatives from the Office of the Auditor General and Archipelago who took the time to speak with our team for the purpose of this article.