Early in the Spring, as the herring begin their spawning season, Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO) attempts to capture the pulse of life beneath the waves. They send planes overhead to document the length of spawn, and afterwards divers into the water, to assess the number of eggs laid and their likelihood of survival. Each year, as herring decline, so do these monitoring efforts. While this data is by no means the definitive way to know how well herring populations are faring, it is a useful tool to compare with previous years, in spite of only painting a small part of the picture.

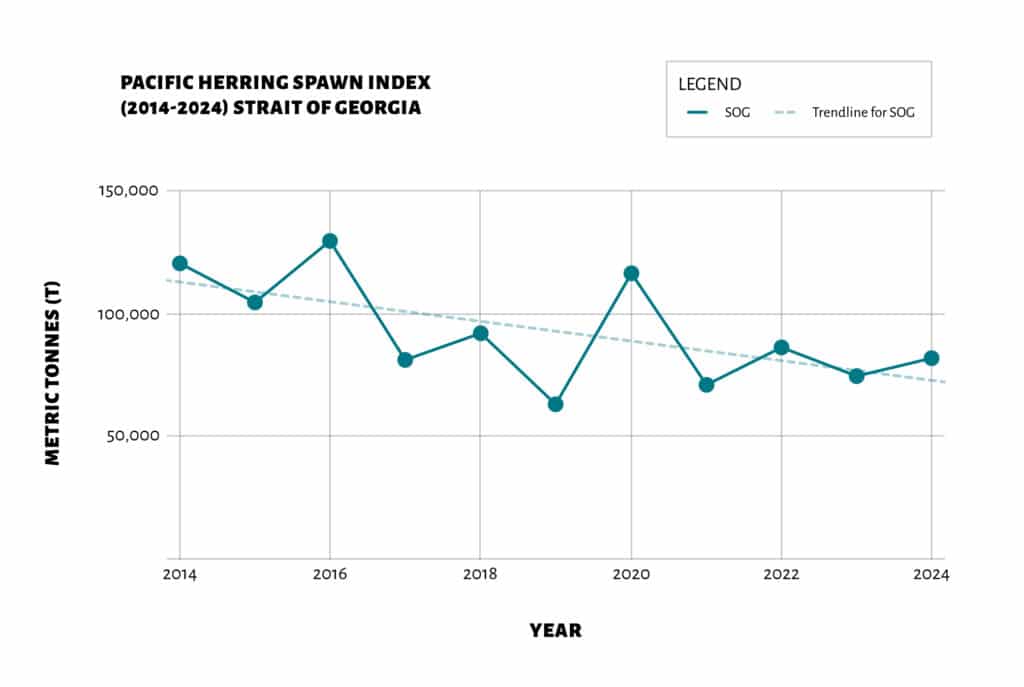

The preliminary data summary from the 2024 herring spawn surveys was released in late July for the Strait of Georgia (SOG), the last stronghold for Pacific herring on the B.C. coast. This area of the Salish Sea is where one of the last remaining herring net-fisheries still takes place in B.C.. While the spawn index – the minimum observed spawning biomass determined from egg counts – in the SOG is marginally higher in 2024 than in 2023, it still falls below the average spawn index of the last decade, a stark reminder of the challenges these vital fish face.

The report included crucial observations contributed by representatives of First Nations communities. QualicumFirst Nations noted that it “seemed like the fish were looking for optimal places to spawn”, that these observations could be a result of a “lack of substrate (e.g., seaweed) to spawn on” (Cleary & Grinnell, 2024, pg. 4). A poignant observation noted that the spawn was “about half of what was observed last year, taking into consideration the narrow spawns and short duration spawns” (Cleary & Grinnell, 2024, pg. 4). The noted reduction by First Nations is not just a statistic; it represents a deepening struggle for survival.

Across the Strait, away from the main spawning areas around Vancouver Island, the Tla’amin Nation were unable to gather any herring or roe from their traditional territory this year despite multiple efforts. This absence strikes at the heart of their cultural and subsistence practices, underscoring the profound impacts of these environmental changes.

Only Part of the Story: What the Spawn Index Doesn’t Tell Us

The spawn index tells only part of the story. The survival of herring eggs and juveniles is intricately tied to ocean conditions, particularly ocean temperature and storm activity. Average annual sea surface temperatures along the coast of B.C. have increased between 0.6 to 1.4⁰C within the last hundred years, with some areas like the Strait of Georgia warming by up to 2.2⁰C per century. For the herring, these warmer waters can present a dire challenge. Research shows that elevated temperatures, especially chronic ones, are devastating for the survival of young herring, pushing them closer to the brink.

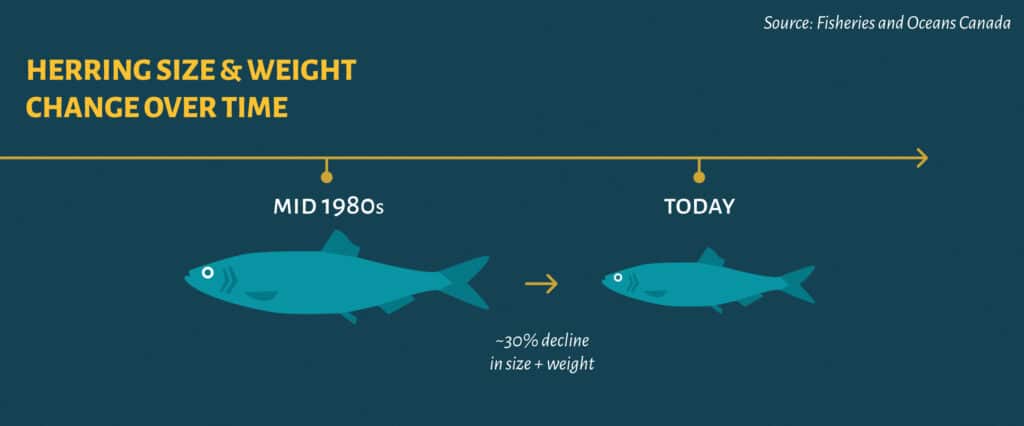

Since the mid-1980s, there have been periods of alarming declines not just in the abundance of herring but also in the length and weight of Pacific herring across all coastal areas of British Columbia (B.C.), with these trends re-emerging in recent years. Individual fish are not growing to the same size that they used to in the past. These reductions in growth, or ‘size-at-age,’ are a consequence of many factors, including decades of intense industrial fishing, climate change and degraded marine ecosystems and are exacerbating herrings’ ability to recover. Age and size at maturation is linked to population productivity, as larger fish typically produce more offspring, and conversely smaller, younger fish have fewer offspring. Therefore as the average herring age and size decreases, the future population biomass is also at risk of decreasing.

The plight of the herring is a stark reminder of our interconnectedness with nature. As these fish struggle to find a foothold in changing seas, so too do the communities that depend on them. Protecting herring means more than conserving a species; it means safeguarding a way of life, a cultural heritage, and an essential piece of B.C.’s food web and economy.

The Strait of Georgia (SOG) in the Salish Sea is one of the last sanctuaries for Pacific herring on the B.C. coast. In 2024, this vital area hosted around 42% of the estimated spawning biomass for all of B.C. Yet, herring spawn in the SOG has been disappearing in a south-to-north pattern and is missing entirely from large swaths of their traditional spawning grounds. Concerningly, the drivers of this trend remain unidentified and unmanaged by DFO in fisheries management plans.

As these spawning grounds shrink and spawning periods shorten, we are losing the behavioral and genetic diversity that is essential to the resilience of the herring population. This is not just the decline of a species; it is the erosion of an ecosystem’s ability to withstand the mounting threats of climate change.

While we cannot immediately halt the complex and far-reaching mechanisms of climate change, we can mitigate its impacts through decisive conservation efforts. One powerful strategy is the implementation of fisheries closures, which can help prevent the loss of critical species like Pacific herring. By temporarily restricting commercial net-fishing activities in critical habitats like the SOG, we can give herring populations the chance to recover and thrive while there remains favorable enough ocean conditions to do so. This preserves biodiversity and strengthens the resilience of ecosystems against the relentless pressures of climate change.

Herring are worth more in the water

On the Atlantic coast of Canada, where herring populations have critically declined, a moratorium has been in place for two years. Unfortunately, fisheries biologists report that the conditions that allow the fish to be able to rebuild are not there, and they do not expect this to change in the near future. This dire situation underscores the urgent need for comprehensive and sustainable fisheries management strategies that prioritise long-term ecological health over short-term economic gain. A recent cost-benefit analysis case study in the Southwest Nova Scotia/ Bay of Fundy area by Oceans North reveals that a rebuilt fishery could be worth as much as 492 million for both the fishery and ecosystem in 10 years. These findings highlight the critical importance of protecting these vital species, not only for the balance of the marine ecosystem but also for the broader economic and environmental benefits they provide.

“Rebuilding forage fish populations can not only lead to stronger fisheries in the future, but also support the health of the ecosystem. Our analysis showed that this has significant economic benefits which can and should be considered by decision-makers.”

Katie Schleit, Oceans North's Fisheries Director

Acting now to protect these herring is essential for the long-term survival of not only the ecosystem but also the fishery that so many communities depend on. Join us in urging Fisheries and Oceans Canada to mandate a managed pause on the commercial gillnet and seine roe fisheries in the 2025 fishing season. We need to take proactive measures, guided by the precautionary principle, to safeguard our precious marine environment.

#ProtectPacificHerring