On Hornby, witnessing the precautionary principle thrown overboard.

By Ian Gill 18 Mar 2019 | TheTyee.ca

Ian Gill, a Tyee contributing editor, is a journalist, filmmaker and social entrepreneur who founded Ecotrust Canada and was its CEO in the U.S. and Australia. Follow him on Twitter at @gillwave.

When the herring finally disappear, we’ll have only ourselves to blame.

Indeed, it sometimes seems blame is about the only renewable resource we can rely upon anymore. There’s certainly been an abundance of it this herring season in the Strait of Georgia, here in the northern reaches of what’s fast becoming the Salish Sewer.

‘You are telling me what I’ve been doing my whole life is wrong.’ Docked at Hornby Island, boat captain Calvin Siider faced off with conservationists, including Ian McAllister (at right), urging closure of BC’s herring fishery. Photo: Ian Gill.

At the dock of Hornby Island’s Ford Cove, a world-weary gillnet fisherman, Calvin Siider, squared off against a conservation group advocating for the closure of the last commercial gillnet fishery on the B.C. coast.

“You are telling me what I’ve been doing my whole life is wrong,” Siider shouted. “We’re making a little bit of money out of this, and you’re trying to rip that out of our lives!”

Siider, while waiting for the signal to go fishing, was variously sitting, pacing, standing and gesticulating from the deck of his boat, Maile III, out of Sointula. A few feet away, just out of throttling distance, stood Ian McAllister, executive director of Pacific Wild.

Pacific Wild, just a day earlier, had posted a video in which McAllister said, among other things, “We really should be leaving this fish in the water … This is basis for the food supply of the entire Salish Sea, the basis of our coastal economy, and yet we’re turning this wild herring into fish farm pellets and cat food. This fishery should not ever have been allowed.”

That didn’t sit well with Siider, 44 years a fisherman. “Somebody’s been trying to shut us down our entire lives.” And now along comes McAllister, to “trespass on my life, my living.”

McAllister doesn’t give an inch. It takes some combination of balls and gall to do what he does — to sail his catamaran, Habitat, into the end game of one of the fiercest storms over resource allocation still blowing on the B.C. coast, to go toe to toe with fishermen like Siider, and bow to bow with some of the biggest boats still working our waters for smaller and smaller catches.

There is an echo here of the infamous standoffs on logging roads in Haida Gwaii, Clayoquot Sound, the Kootenays, the Stein Valley, the Skagit, pick your spot — and of the enduring faceoffs over tarsands pipelines and mines and dams and fish farms and tanker bans, among other so-called policy “choices” that we leave to the least qualified people in the world, politicians, to adjudicate, based on what they piously claim to be reliable science that supports their even more reliable need to shore up their prospects of re-election with evidence of economic growth and jobs for middle-class Canadians.

Jonathan Wilkinson, our federal fisheries minister, personifies the Trudeau-era cabinet-minister-as-dittohead. “It’s in the national interest. It’s in the national interest,” they all chant about the orca-killing Trans Mountain Pipeline Expansion project, all evidence to the contrary. In the case of the herring fishery, “We make our decisions based on science,” Minister Wilkinson says reassuringly, if credulously.

And so this year, while all that science-based management has led to the closure of commercial fisheries in four other major areas of the coast — Haida Gwaii, Prince Rupert, the central coast and the west coast of Vancouver Island — the minister took the advice of his boffins and approved the extraction of 21,493 tonnes of herring in the Strait of Georgia. By Pacific Wild’s calculation, that’s 130 million fish. As of Saturday, the seine fleet had successfully killed about half that number; over the weekend, the gillnet fleet was on target to finish the job.

The science that the minister relied upon to set this year’s catch can be foundin one of the products of the Canadian Science Advisory Secretariat, its Pre-Approved Draft: Status of Pacific Herring (Clupea pallasii) in 2018 and Forecast for 2019. For the layperson, parts of it are a little hard to fathom:

“A Bayesian framework was used to estimate time series of spawning biomass, instantaneous natural mortality, and age-2 recruitment from 1951 to 2018. Advice to managers for the major stock areas includes posterior estimates of current stock status (SB2018), spawning biomass in 2019 assuming no catch (SB2019), and stock status relative to the LRP of 0:3SB0. The Markov chain Monte Carlo sampling procedure follows the same method implemented by Cleary et al. (2018) with chain length 5 million, sampling frequency of 1,000, and burn-in of 1,000. The resulting 5,000 samples are used to calculate median posterior estimates of spawning biomass (for example) and associated 90 per cent credible intervals.”

The idea of a “Monte Carlo sampling procedure” being used to evaluate the crapshoot that is fisheries stock assessment strikes me as disconcerting, but I am assured by Victoria Postlethwaite, regional herring officer for Fisheries and Oceans Canada, that “the Strait of Georgia aggregate stock biomass is currently estimated to be in the top one third of the biomass time series since 1950. The aggregate stock has remained highly productive and has supported a 20 per cent harvest rate for a prolonged period of time.” In other words, relax, there are plenty of fish.

Even if that were true at the moment, a 20 per cent harvest rate doesn’t exactly indicate that a precautionary principle is top of mind among fisheries scientists who, in the same report, concede that “the most effective means of mitigating stock assessment errors (would be) reducing the absolute size of the catch… from 20 per cent to 10 per cent.”

Vanessa Minke-Martin, marine science and communications specialist with Pacific Wild, counters that the government’s report notes a decline in spawn index values for the past three years. There is “insufficient information to determine if the decline from 2016 to 2018 represents a decline in spawning biomass. It may require a few more spawn index observations to resolve whether a change in spawning biomass trajectory has recently occurred,” the report says.

So how trustworthy is the science, or more to the point, the decision to prosecute a fishery of any size right now when the amount of herring spawn appears to be declining? Minke-Martin would like to know: Since DFO itself concluded the safest thing to do is cap the harvest at 10 per cent, why did it authorize one twice as large? She calls that decision a scientific “non-sequitur.”

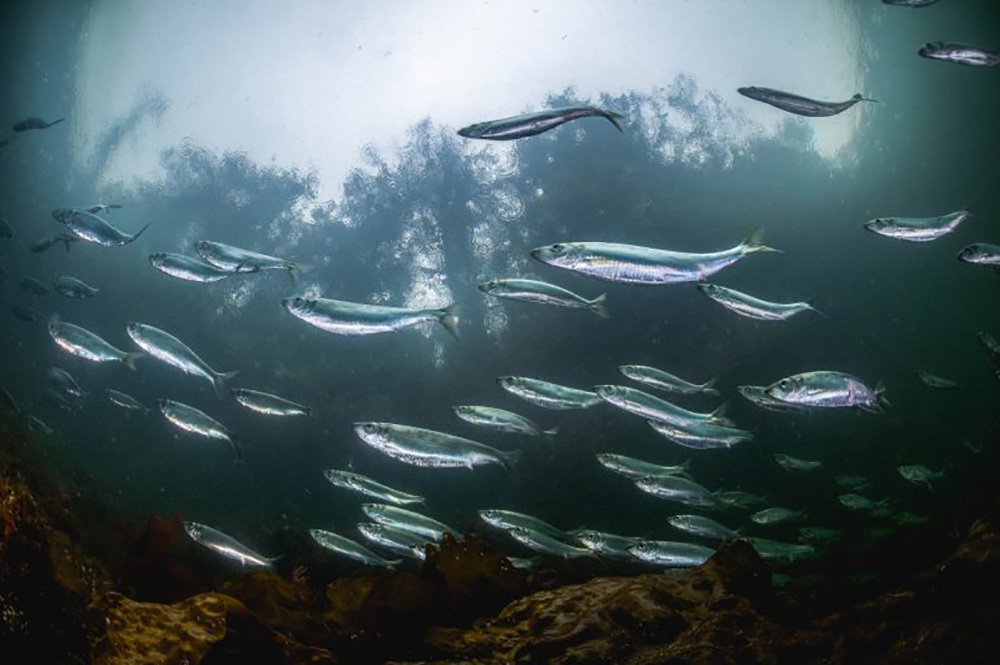

The DFO says herring stocks could this year withstand a robust harvest in the Strait of Georgia. Critics, including Stephen Hume, point out federal fisheries managers greenlighted East Coast cod catch right up until they crashed. Photo: Pacific Wild.

At some point, you have to wonder how many fisheries scientists can dance on the head of a pin. Rightly or wrongly, Ottawa thinks the fleet can take 130 million fish out of the water without making a dent in the stock’s “long-term” ability to reproduce. Locally, confidence in that decision is low.

Grant Scott, who chairs Conservancy Hornby Island, says his community first put on a herring festival two years ago as a seasonal celebration of the herring spawn. Within a year it had dawned on them that the festival might better be used to publicize how dire the prospects for herring are. This year, an online petition calling for the fishery to be closed has attracted close to 72,000 signatures and counting.

On the Ford Cove dock, Scott, too, gets into a scrap with Calvin Siider. Scott says allowing the fishery “defies any logic. I think we should be leaving these stocks to rebuild in the whole of the Strait of Georgia.” Siider shakes his head in disgust.

‘Just a matter of time’

Farther north, while the fleet is not fishing in Tla’amin Nation territory, DFO’s decision-making has the nation worried. “What we’ve done is we’ve asked [DFO] to stay out of the inside waters here,” says Tla’amin hegus [leader] Clint Williams. “I’m still not a 100 per cent believer in their science…. Their science said they could fish on the inside here and it’s just devastated the fishery here,” dating back to the mid-’80s. Williams doesn’t trust DFO to keep the fleet at bay. “It’s just a matter of time before it gets up this way.”

To the south of the fleet, another long-term resident and observer of the Salish Sea, Stephen Hume, writes, “If science is so good at predicting abundance, why are 80 per cent of herring sites now closed?

“We’ve fished stocks to collapse before, amid repeated assurances that the fisheries science shows harvests to be sustainable,” he reminds. “In the 1950s, overfishing of Japan’s herring led to a collapse. In the 1960s, the California sardine fishery collapsed. Herring fisheries in Alaska and B.C. were closed in the 1960s after overfished stocks collapsed. Overfishing destroyed herring stocks off Iceland, Norway and Russia around the same time. In 1972, the overfished Peruvian anchovy fishery collapsed. In 1992, Canada’s Atlantic cod went the way of the herring, sardines and anchovies. Cod stocks that had supported Newfoundland fisheries for 500 years suddenly fell to one percent of what it had been at its maximum biomass.”

“One common factor in these serial fisheries disasters,” Hume writes, “is that regulators were convinced harvests were sustainable — until they suddenly weren’t.”

Hume shares an anecdote about his father-in-law having used a herring rake, a kind of paddle fashioned with teeth like a comb, to catch herring that were so plentiful you could just sweep them out of the water. Even in the 1980s, when I first came to these parts, I fished with a guide — from one of those hyphenated old B.C. families, a McTaggart-Cowan, a Haig-Brown, maybe a Bell-Irving — who showed me how to jig for herring to use as bait for catching Chinook salmon. There was never a moment’s doubt there’d be herring there, or salmon. It might sound wistful, but that memory does seem of a distant time and place where our human pursuits were more in tune with what nature offered in abundance.

Now, everything seems so wildly out of balance — perhaps no more so than in the Salish Sewer.

Consider a video posted on Facebook just before the herring fishery opened, which shows a B.C. fisherman throwing a bear banger — a small explosive device used to frighten wildlife — into a raft of sea lions. The fisherman, Allan Marsden, was reportedly collecting herring samples when his boat was surrounded by sea lions. He may yet face charges for “disturbing” wildlife.

Disturbing wildlife is quite a thing at the moment. There are now “wolf-whacking” ads on Facebook if you can believe it, promoting three separate contests in our province where hunters are invited to kill predators — like wolves, coyotes, cougars or raccoons — and win a prize. The Creston Valley Rod & Gun Club’s “predator tournament” is on right now until March 24, “open to all sportsmen,” and will culminate on Sunday with a predator count, BBQ, bonfire and prizes at Kid Creek rifle range. “Must bring your harvest whole, hide or unboiled skull for proof.”

Meanwhile, back on the water, the Pacific Balance Pinniped Society has proposed to DFO that it authorized a commercial seal hunt. It blames exploding seal and sea lion populations for threatening salmon stocks, along with their being a nuisance to fishermen. There’s no data to suggest a cull would help salmon species, according to Dr. Peter Ross of the Vancouver Aquarium. “Personally and professionally, I don’t think it would make an ounce of difference,” he told the National Post.

Andrew Trites, who oversees the marine mammal research unit at the University of British Columbia, also warns that culling seals and sea lions would have consequences down the food chain, particularly for the transient killer whales that eat them. “What I see the issue being here is, for some people it’s not a question of sharing an ecosystem, it’s an issue of controlling it,” Trites said.

‘I’m trying to be able to afford a house’

As for sea lions being a pest, well that’s an easier argument to make. On the Strait of Georgia last week, seine boat fishermen in Northwest Bay, just north of Nanoose Bay, set their nets for herring and caught mostly sea lions instead. Looking up from the bay, the eastern slopes of Vancouver Island are being logged again, every hillside looking like a ski slope after the recent snow — but no, those are just more clearcuts. Along the Qualicum shore is a growing fringe of resorts and retirement homes. From the warmth of their living rooms, people can look out on herring fishermen engaged in the dangerous business of untangling sea lions from their nets, almost as good as reality television. At some point, you do wonder if the fishermen’s historically meagre haul of a dwindling resource is really worth pursuing at all.

Alistair and Kingsley Bryce think so. They are brothers, born and bred in Nanoose Bay, “lifelong fishaholics,” says Alistair, 22. They’ve been fishing since they were 12 years old. Kingsley, 24, says “we have never participated in a fishery with this kind of tension before.” Nonetheless, he and Alistair want to keep fishing. “I’m trying to be able to afford a house,” Alistair says. Just in their short time in the fishing industry, they’ve seen a downward spiral, salmon in particular, but “I don’t think herring is going to die out like some people say it is,” Alistair says. “The percentage that we’re taking out with our nets, it’s not a huge amount of the biomass.”

But they make that call based on what they’ve seen, rather than any faith in fisheries science. “In my estimation nobody’s right, including DFO,” Kingsley says. “It’s the ocean!” Or as Stephen Hume calls the Pacific, it’s “a ‘black box’ in which mysterious things happen which affect salmon, herring, tuna and other fish (and) the emperor of science turns out to wear no clothes.”

Brothers Alistair (left) and Kingsley Bryce, in their early twenties, have been fishing since they were 12. ‘The percentage that we’re taking out with our nets,’ says Alistair, ‘it’s not a huge amount of the biomass.’ Photo: Ian Gill.

Pacific Wild has produced an analysis — Top Ten Arguments against the Strait of Georgia commercial seine and gill net herring fishery — and, going to some lengths to reference its conclusions to available science, ends up citing DFO on almost every page. Whether that science can be trusted or not is hardly Pacific Wild’s responsibility; whether its interpretation of DFO science can be trusted, is. But one of the failings of our resource management system now, especially after the Harper years but even now in the Trans Mountain era, is that our agencies are so deeply distrusted because they are so deeply conflicted.

Agencies like DFO and the National Energy Board have tremendous research budgets and their conclusions are backed by authority of law, but they’ve become what environmental lawyer Eugene Kung has referred to as “captured regulators.” They can no longer be trusted to interpret their research in the public interest because of the pressure of private interests: respectively, commercial fishing and fish farm industries, and in the case of the NEB, powerful energy interests.

So it is that the NEB can study the threats to resident killer whale populations in the Strait of Georgia, conclude that the Trans Mountain Pipeline Expansion will endanger the orca population, and go ahead and approve the pipeline anyway.

So it is that DFO can approve a commercial fishery on one of the principle sources of food for Chinook salmon, which are in turn one of the principle sources of food for killer whales.

So they take herring out of the mouths of Chinook out of the mouths of orcas. And then on Friday comes the latest out of the politicians’ mouths and taxpayers’ pockets — $143 million over five years to, you guessed it, protect wild salmon.

Minister Wilkinson reiterated his belief that the pipeline won’t harm salmon. Premier John Horgan says it very much might. “The consequences of a diluted bitumen spill would be catastrophic for our marine environment that includes Chinook and salmon and southern residents.” And around we go, all about as scientific as a game of Wheel of Fortune.

Back at Ford Cove, Calvin Siider denounces McAllister. You “blatantly, scandalously spout your propaganda,” Siider says, defending his 86.4-ton allocation, which will fetch him about $800 per ton when he’s done, or about $70,000 before expenses.

One of Pacific Wild’s 10 points is that “herring fishers are making a fraction of what they made three decades ago — for the same quantity of fish. For example, in 1990, the average value per ton was $2,880, over three times more than the average of $840 per ton that fishers earned in 2017.”

Siider shakes his head. “Show me some paperwork!” Oh but there’s plenty of that, all the scientific and economic analysis you could ask for, and more. That’s never been the problem.

Later, Siider almost pleads for understanding from Grant Scott, who he’s known for 40 years. “There’s still 25 of us struggling away to raise our families,” he says softly. And then, in an unguarded moment, he allows, “It’s not coming back Grant.” And he sits down, and looks away.

Late bulletin

At 7:30 a.m. Saturday, with the seine fishers having packed up and left after netting most of their quota, DFO managers opened the gillnet fishery off Denman Island and Calvin Siider got to go fishing for his. Pacific Wild flew a drone over the fleet, filming what McAllister calls a “Wild West” assault on the fish. “Bear bangers, shot gun blasts, you could hear it from 10 kilometres away. It’s so industrial, such an insult to the fish, and no one (from government) to enforce it, even witness it.” (The video is here.)

The department issued a bulletin confirming that “DFO Resource Managers have left the grounds,” leaving the gillnet fleet to manage itself. If nothing else, it probably saves a lot of paperwork.