The management of Pacific Salmon has proven to be a daunting task for fisheries managers in British Columbia. The very foundation of salmon stewardship requires the annual monitoring of thousands of watersheds in coastal B.C. in order to assess the health and abundance of spawning salmon. Still today, this task is undertaken through the hard work of creekwalkers, charter patrol contractors and Indigenous guardians who physically count spawning salmon in their natal streams. All other points of their life cycle, from tiny alevins to multi-year ocean migtration remains largely unknown and undocumented. A study conducted by Price et al. (2007) evaluated the efficacy of current management regimes, specifically by Fisheries and Oceans Canada.

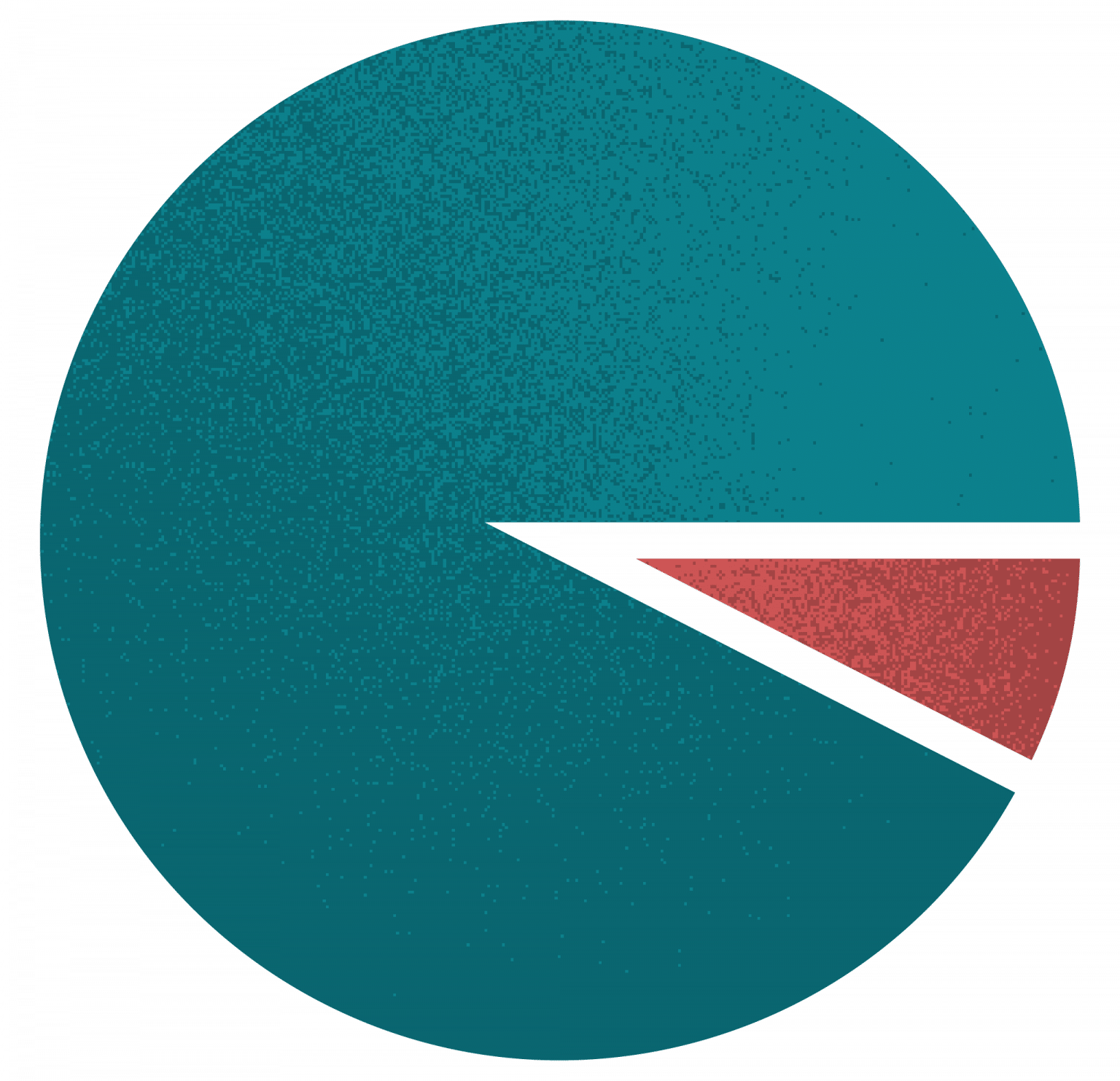

Currently there are 215 out of the 2,592 spawning streams that are monitored in the central and north coast regions. It was determined that only 4% of those monitored streams met target escapement levels.

For the process of monitoring, streams are organized into Conservation Units (CU) and indicator streams. All surveyed spawning streams in the Central Coast have been classified as indicator and non-indicator streams. Indicator streams are streams that have been identified by DFO, in consultation with the Pacific Salmon Foundation, as providing more reliable indices of abundance (see English et al. 2006 for details). These indicator streams tend to be more intensively surveyed using methodologies that are trusted and provide relatively accurate estimates of annual abundance. Indicator streams are also assumed to be representative of returns to other streams within proximity. Non-indicator streams within the Conservation Unit may also be surveyed each year. Non-indicator streams typically have less consistent survey coverage, variable methods applied, lack of survey funding and/or may simply be difficult to survey (e.g. poor water clarity, remote location). A Conservation Unit (CU) may comprise more than one spawning population, and the monitoring coverage of spawning populations has varied greatly over time. Moreover, only very rarely are all the salmon spawning populations that comprise a CU actually counted in a given year (English et al. 2016). There are a total of 3174 spawning streams in British Columbia, with 781 designated as indicator streams for monitoring (English et al. 2006).

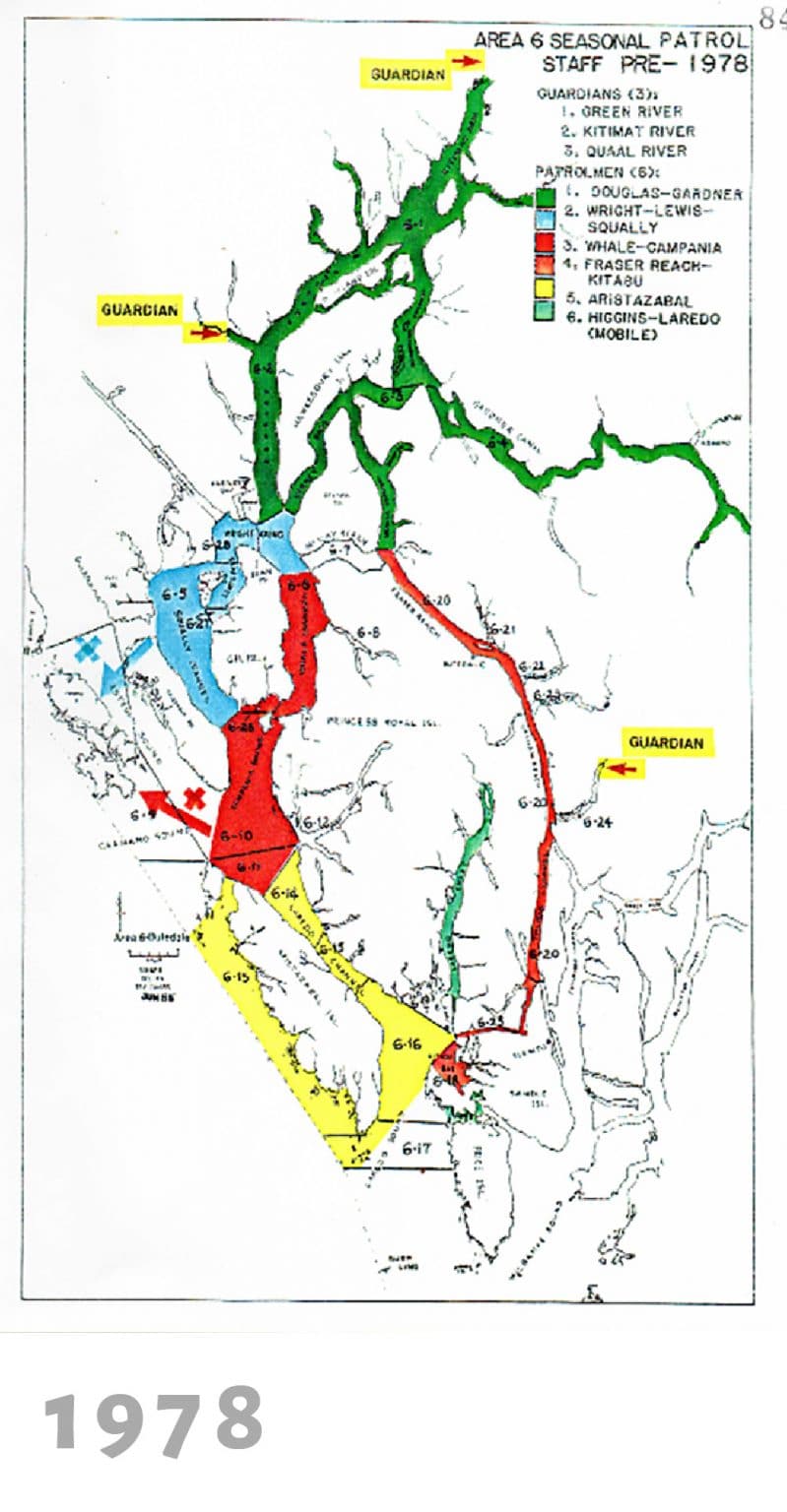

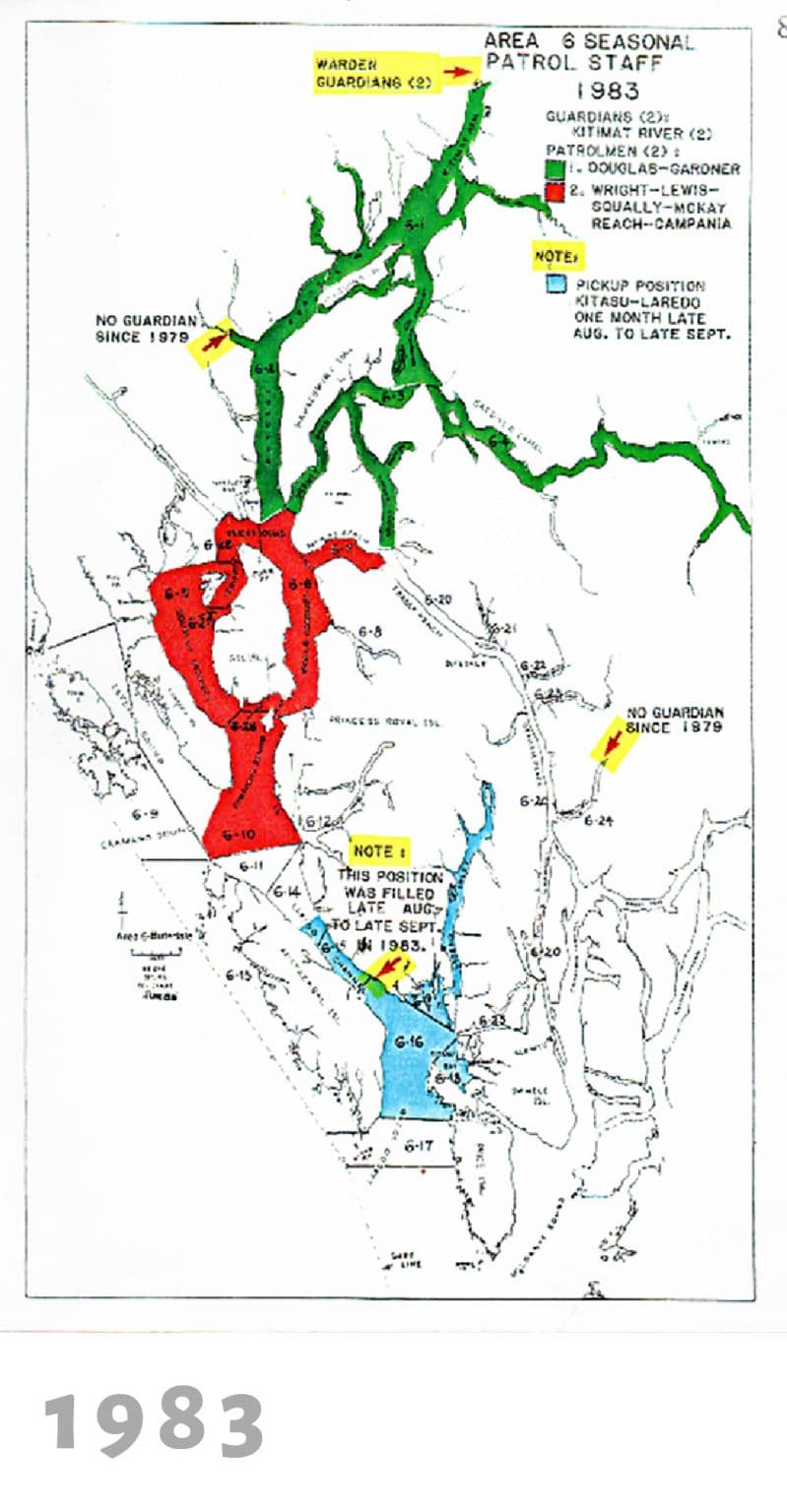

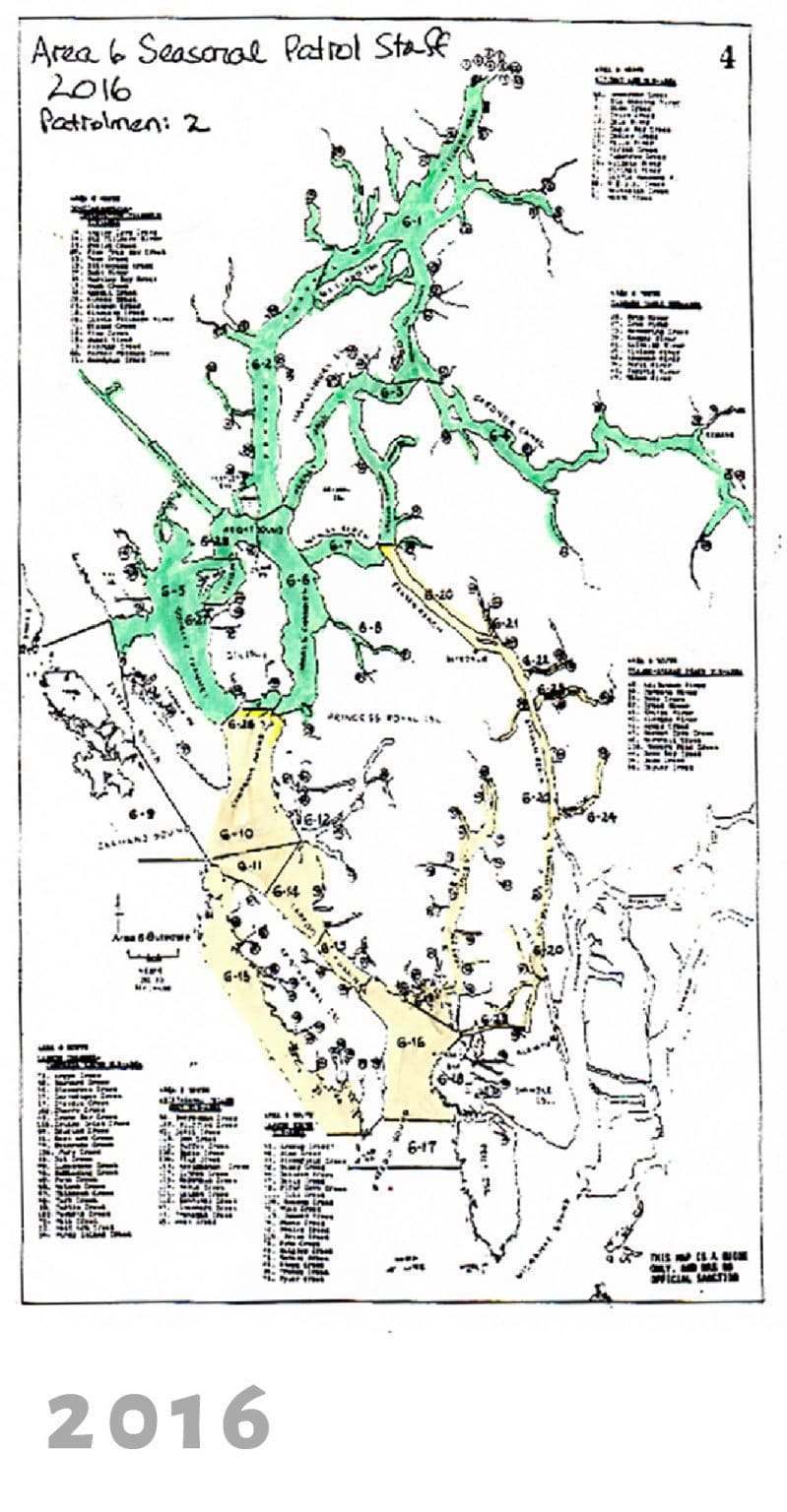

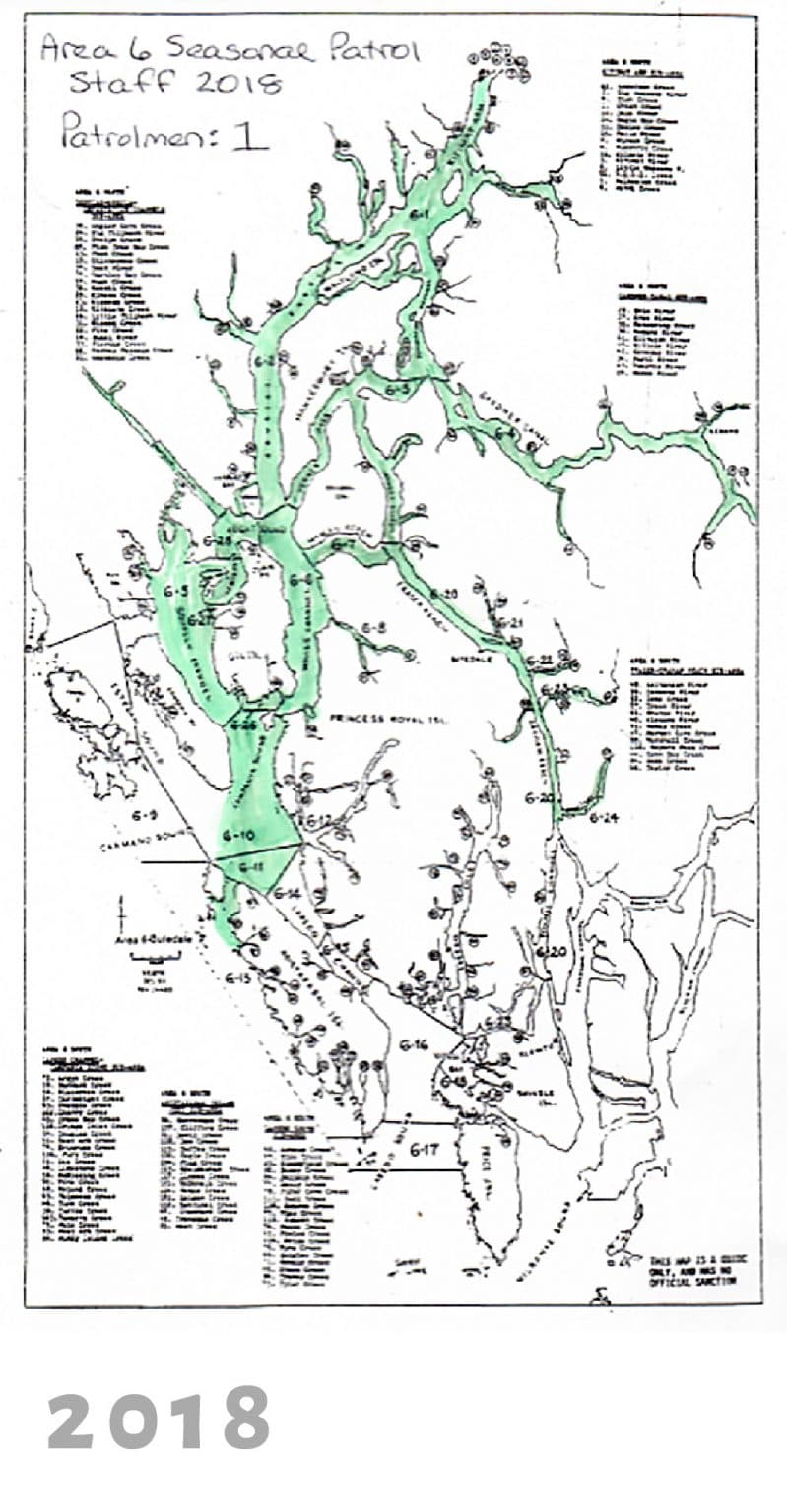

These maps show where salmon have been monitored by Charter Patrolman in Area 6 between 1978 and 2018. Today, only one Charter Patrolman remains due to cuts made by DFO.

Currently, Fisheries Officers only have the funding for the deployment of one boat patrol for the region stretching from Port Hardy to Alaska. There are presently only two Charter Patrolmen that have existing contracts on the North Coast, and while they share between them over 100 years of combined experience counting salmon, they represent just a fraction of former government investment in monitoring and enforcement. Creekwalkers know, through years of irreplaceable field experience how to access each river, when to count each run, where in the river the salmon will spawn, and how to count each specific species of salmon. This critical documentation allows fisheries managers to understand long-term trends in salmon abundance and decline. Unfortunately, the number of spawning streams that are monitored by DFO continues to decrease. Additionally, there is evidence indicating that the streams selected for monitoring are larger runs that continue to have the ability to support salmon, while the smaller, decreasing and extinct runs have been left unobserved.

In the last 15 years, DFO funding for salmon escapement programs has been cut by over 60% (English et al, 2016; MacDuffee & Harvey, 2002). Salmon are counted in less than half of the streams in the North Coast. Over the last 80 years, most escapement data in the North Coast has come from Fisheries Officers and Charter Patrol programs, whereas funds from DFO to support knowledge of salmon escapement have been consistently reduced.

Works Cited

- English, K.K., Mochizuki, T., and Robichaud, D. 2011. Review of north and central coast salmon indicator streams and estimating escapement, catch and run size for each salmon Conservation Unit. Prepared by LGL Limited Environmental Research Associates for Pacific Salmon Foundation, Sidney, BC.

- Harvey, B., and M. MacDuffee — editors. 2002. Ghost Runs: The future of wild salmon on the north and central coasts of British Columbia. Raincoast Conservation Society. Victoria, BC.

- Price, M. H., Darimont, C. T., Temple, N. F., & Macduffee, S. M. (2008). Ghost runs: Management and status assessment of Pacific salmon (Oncorhynchus spp.) returning to British Columbia’s central and north coasts. Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences, 65(12), 2712-2718. doi:10.1139/f08-174