There are two keys steps to escapement monitoring:

- Obtaining reliable estimates of escapement from a representative set of ‘indicator’ streams.

- Using habitat models to determine the proportion of total escapement represented by the indicator streams.

However, there has been a shift in monitoring as assessments are being conducted on fewer indicator streams (DFO now focuses mostly on large river systems). In addition, varying methods are used in monitoring in B.C. spawning streams: direct DFO monitoring, non-governmental organizations, Indigenous Nations monitoring and community-based contractors (Harvey & MacDuffee 2002). Indigenous Guardians and local Creekwalkers are practical avenues for DFO to allocate funding for enhanced salmon monitoring. It is increasingly clear that there is a lack of funding allocated to properly monitor all of British Columbia’s key indicator streams. Without proper monitoring and annual stock assessments the status of wild salmon is at best a guess.

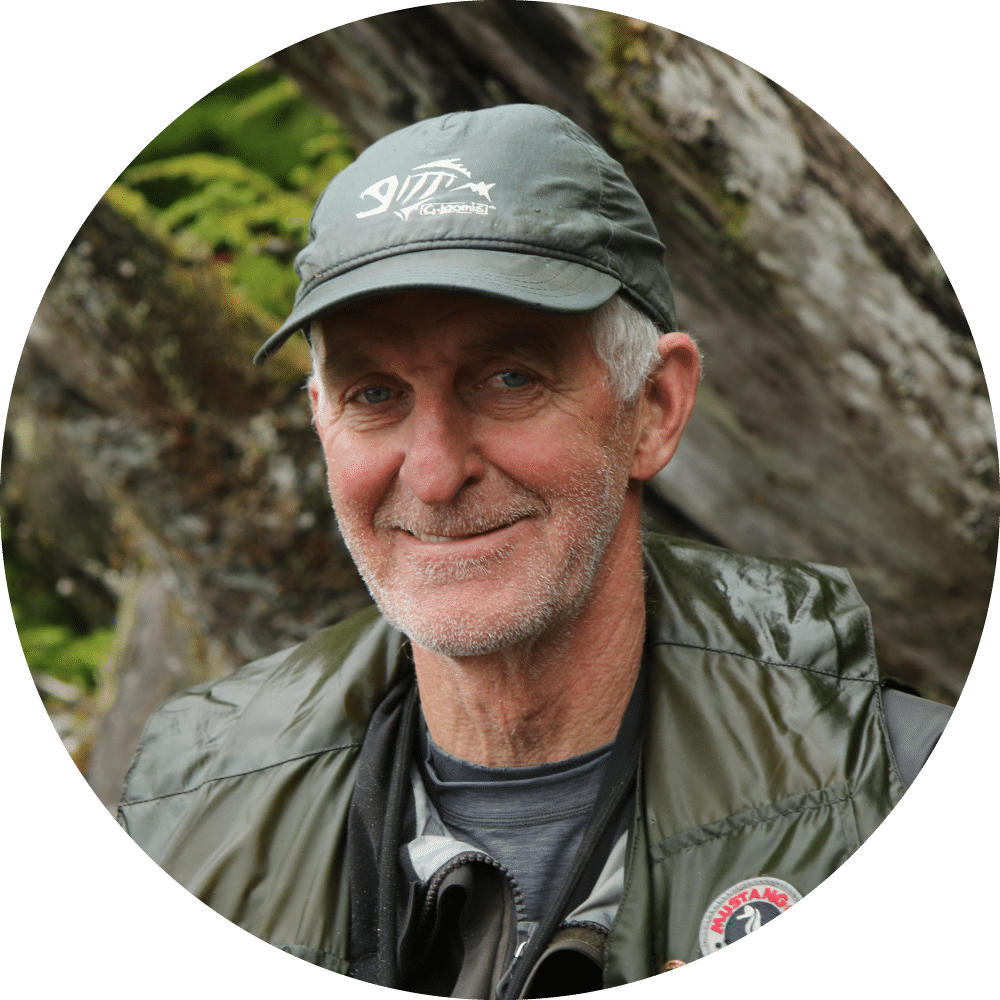

Local Charter Patrolmen

Doug Stewart’s first year as a contracted Fisheries Charter Patrolman for wild salmon began in 1977. Year after year he walked the rivers and creeks of B.C.’s Fishing Area 6, in the heart of the Great Bear Rainforest, counting salmon for the next 40 years until finally retiring in 2016. He didn’t stop until his knees could no longer carry him over fallen logs and rocky shores to the headwaters of rivers where salmon spawned. Stan Hutchings is now the last fisheries patrolman in this area, covering over 16,900 kilometres (10,000 square miles) of area including approximately 150 spawning streams. Not many years ago, most of these streams would have been counted but due to budget cuts last year Hutchings was able to walk just over 50 of those streams.

Stewart and Hutchings are known as Creekwalkers: charter patrolmen, guardians, and volunteers. They are conservation’s essential window into the Central and North Coast salmon runs, and their duties are numerous. They are responsible for recording salmon numbers, conducting stock assessments, monitoring closed areas and net fisheries, compiling biological data collection and connecting with local stakeholders. Most importantly, they provide detailed assessments of the amount of salmon that return to their natal streams. From an area perspective, these tasks seem daunting. With 575 nautical miles of spawning grounds and channels in Area 6 alone, Hutchings currently monitors over 1400 nautical miles of coastal area, 2166 nautical miles of spawning rivers, and 650 nautical miles of interior streams.

responsibilities of a charter patrolman (to name a few)

counting salmon and conducting stock assessments

closed area patrols

biological data collection

connecting with local stakeholders

Being a creekwalker is not easy. They are not Department of Fisheries and Oceans (DFO) employees, but rather contracted individuals required to provide all necessary equipment: the vessel, crew, and all technical equipment. This is a huge personal investment but is essential to being able to safely and efficiently cover as much ground as possible during the relatively short spawning season. There are currently only two North Coast charter patrolmen, leaving the Central and North Coast spawning streams severely under-monitored and under-managed. In the absence of government funding Indigenous Nation communities are increasingly undertaking salmon counts in their respective territories but it is often at the expense of other stewardship priorities and generally lacks sustained funding and support from DFO.

"There is no magic to counting salmon in streams on the coast. It takes a few years of experience to develop the skills as well as a willingness to work in the wilderness, often in inclement weather. Most people, when counting large numbers of anything, tend to count low. For salmon, it is the consistency of the count that is important. Having the same person, counting the same stream, the same way, at the same times, year after year, estimating the number of spawners allows a trend to develop."

— Stan Hutchings, Area 6 Charter Patrolmen

Guardian Watchmen Program

Indigenous Guardian programs play a critical role in land and marine stewardship for coastal First Nations. They are effectively the eyes and ears out on the lands and waters of their respective territories. Indigenous Guardians ensure that resources are sustainably managed and that land and marine resource use agreements are implemented and upheld effectively. Each Nation has a unique Guardian program to carry on its stewardship traditions, to uphold Indigenous Law and to protect land and sea. In turn, Indigenous Nations are working with the Crown governments to strengthen the role and increase authority of Indigenous Guardians.

Indigenous Nations Stewardship Programs

When discussing monitoring and conservation, Indigenous Nations are at the forefront of expertise and effort. As an example, the Kitasoo/Xai’xais Nation have been running a smolt monitoring program since 1992 in two spawning creeks. This monitoring program uses fyke nets (a type of fish trap) to monitor out-migrating Sockeye, Coho, Pink, and Chum smolts (Pacific Salmon Foundation, 2017). The Pacific Salmon Foundation partners with the Central Coast Indigenous Alliance, the Nuxalk, Kitasoo/Xai’Xais, Heiltsuk, and Wuikinuxv Indigenous Nations to identify management methods and recovery actions. This may be the most beneficial method to form strategic decisions on how to focus efforts for salmon enumeration in the future. In Area 6, the Gitga’at, Haisla, and Kitasoo/Xaixais Indigenous Nations provide Guardian support. The Gitga’at and Haisla also fund helicopter assessments that were cut from the DFO budget for Area 6.

SFU Reynolds Lab / Heiltsuk

For the last 13 years, Reynolds Lab researchers have partnered with the Heiltsuk Indigenous Nation to count salmon in 25 salmon streams in Heiltsuk Territory. Watch our video to get a glimpse into their process and learn about the importance of salmon monitoring in B.C.’s smaller streams which are often overlooked by the government.

Restoring funding to enumeration of natal streams each year should be a priority for the DFO. Without this funding we lose our only real connection to the health and status of wild salmon. For too many years, the North and Central Coast monitoring programs have suffered from budget cutbacks and the DFO has never had a weaker presence during salmon spawning season than exists today. Unbiased, sustained data collection and biological sampling is necessary for accurate long-term assessment of salmon data now and into the future. Restoring long term funding, training programs and increasing enumeration should be considered the first line of defense in the conservation of wild salmon.