Do You Caribout Wolves?

We believe caring about wolves IS caring about caribou. The ongoing destruction of critical caribou habitat is causing their decline and we don’t need to kill wolves to save caribou.

why caribout wolves?

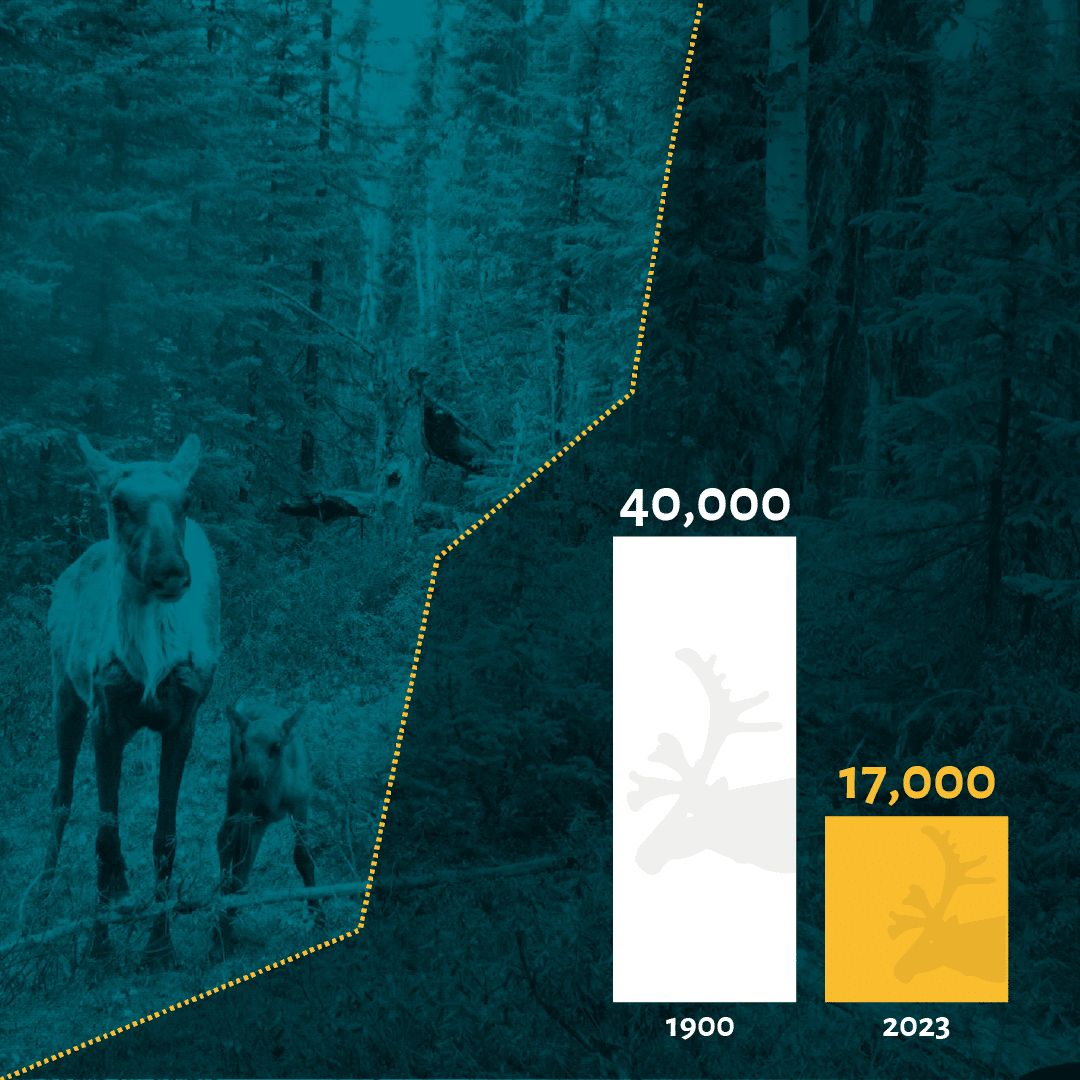

Why are we talking about caring about caribou and wolves? The British Columbia (B.C.) government linked the health of these two species eight years ago when the Province started a taxpayer-funded wolf cull to support the recovery of endangered caribou herds in B.C.. In less than a century, the British Columbia (B.C.) caribou population has declined from around 40,000 to a mere 17,000 distributed among 54 herds of woodland caribou (Rangifer tarandus caribou).[i],[ii] Several caribou herds are extirpated (locally extinct) and more are expected to follow in the coming years. The B.C. government admits that the cause of this decline is loss of habitat, however instead of halting habitat destruction, it has invested over 10.1 million dollars in a predator reduction program primarily targeting grey wolves (Canis lupus). Since the decline of caribou populations in B.C. is caused by ongoing destruction of critical habitat, killing wolves does not solve the problem of caribou decline.

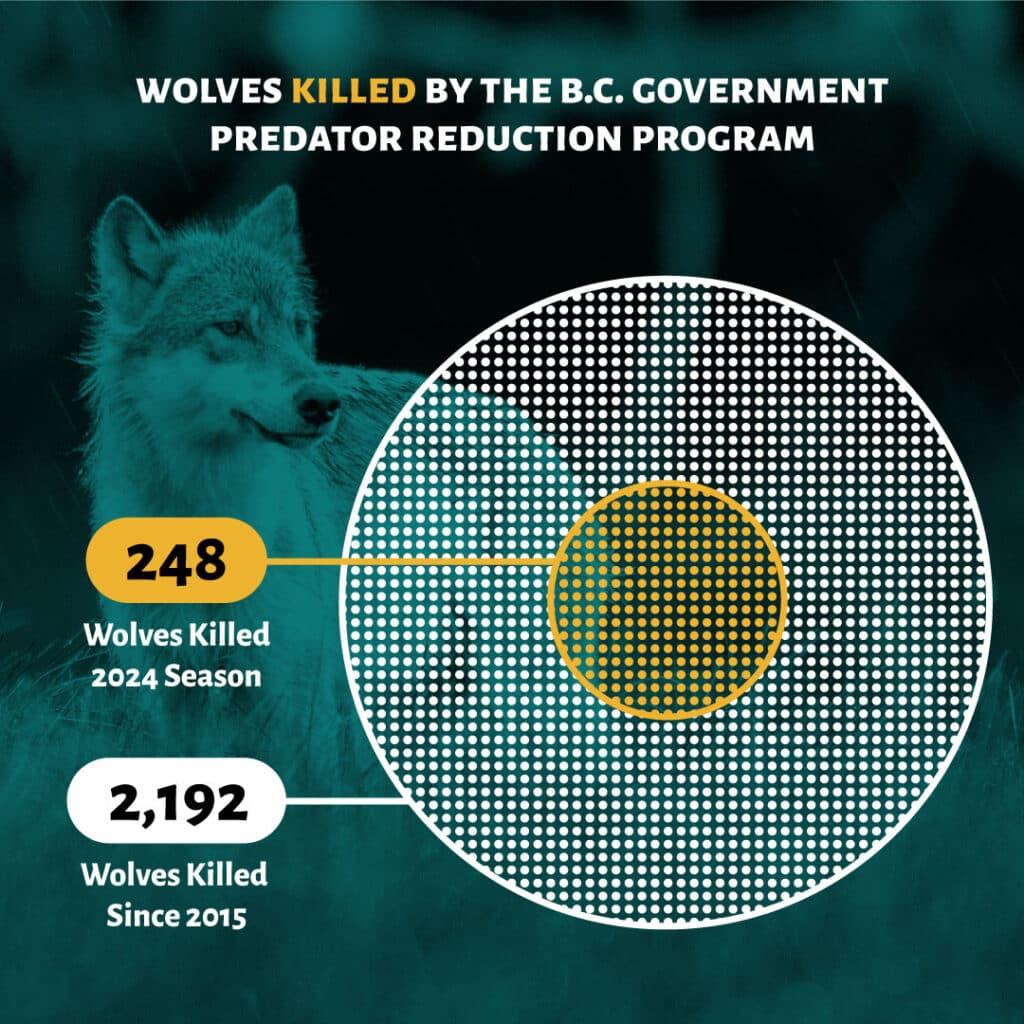

Over 2,100 wolves have been killed since the program started in 2015, along with a smaller number of other predators such as cougars and bears costing taxpayers over 10.1 million dollars to date. The vast majority of wolves have been shot from the air, making the cull not only expensive but also inhumane.[iii],[iv],[v],[vi] Wolves are mostly killed by contracted shooters via helicopter, which often follow one radio-collared ‘Judas’ wolf back to the pack, using the family structure to eradicate more of the pack. Helicopters chase the wolves from low flying heights, creating intense fear, and with little chance of escape. Wildlife experts contend that shooting a moving animal from a helicopter is not in accordance with the Canadian Council of Animal Care (CCAC) guidelines as it is error prone and causes long and painful deaths to wolves[vii]. Furthermore, evidence to support extermination by aerial shooting as a humane method is not adequately documented in the scientific literature.

Recovery means self-sustaining caribou populations. For a species to survive, they require suitable habitat. The provincial wolf cull program is unsustainable,[viii],[ix] unscientific,[x],[xi] unethical,[xii] unacceptable to British Columbians,[xiii] and simply unjust.[xiv] Scientists resoundingly assert that in conjunction with long-term restoration of critical habitat, managing animal movements in the altered landscape to reduce encounters between wolves and caribou offers a cost-effective short-term alternative to the cull.[xv] Experts in Alaska are reporting that the Mulchatna caribou herd populations continued to decline despite decades of wolf and bear killing, largely due to poor body condition from lack of food, and an increase in brucellosis tied to the lack of predation on diseased animals, allowing brucellosis to spread through the herd.[xvi] Apex predators like wolves help regulate species health and play a critical role in maintaining a functioning ecosystem. From songbirds to the shape of rivers, wolves have a profoundly important place in the food web and the landscape.

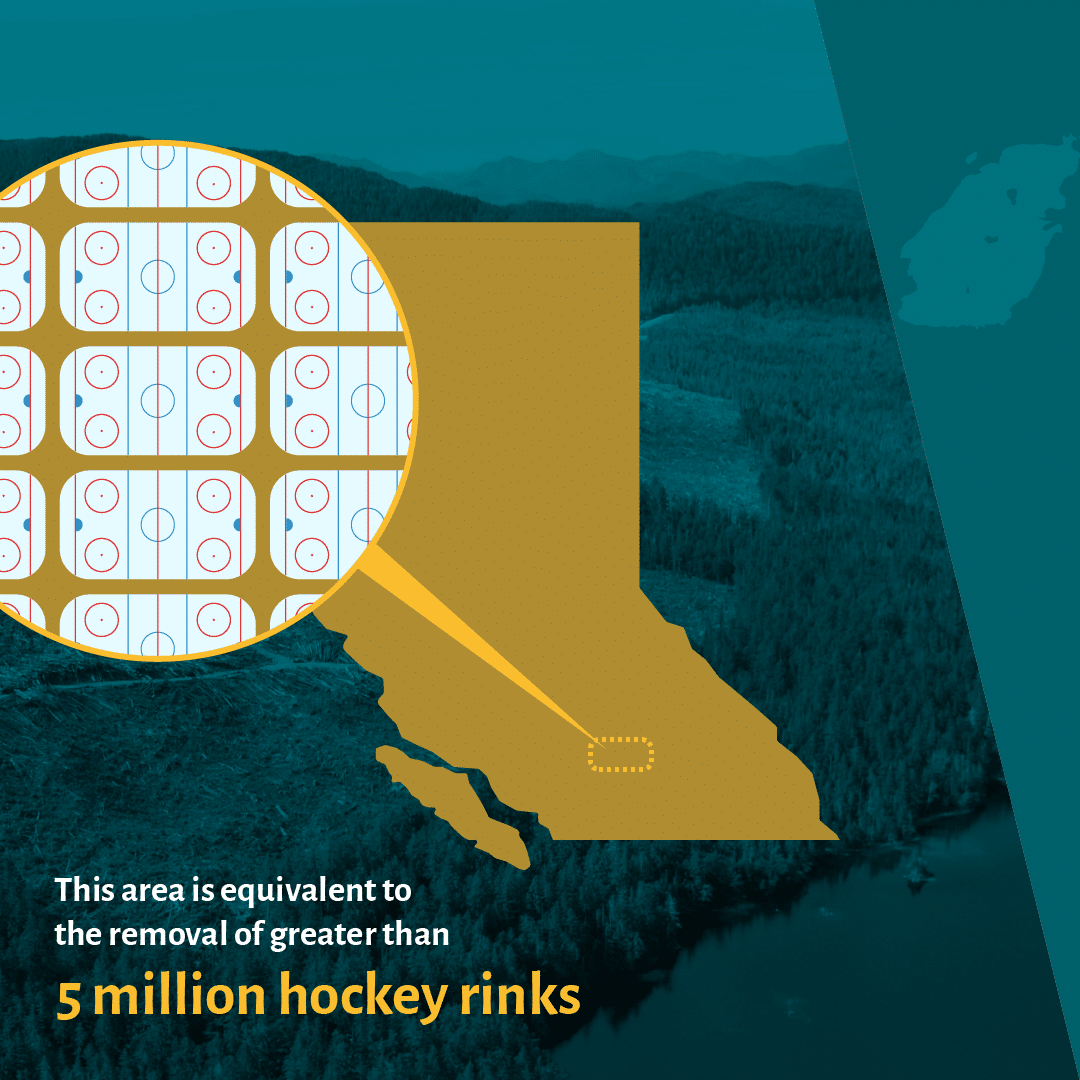

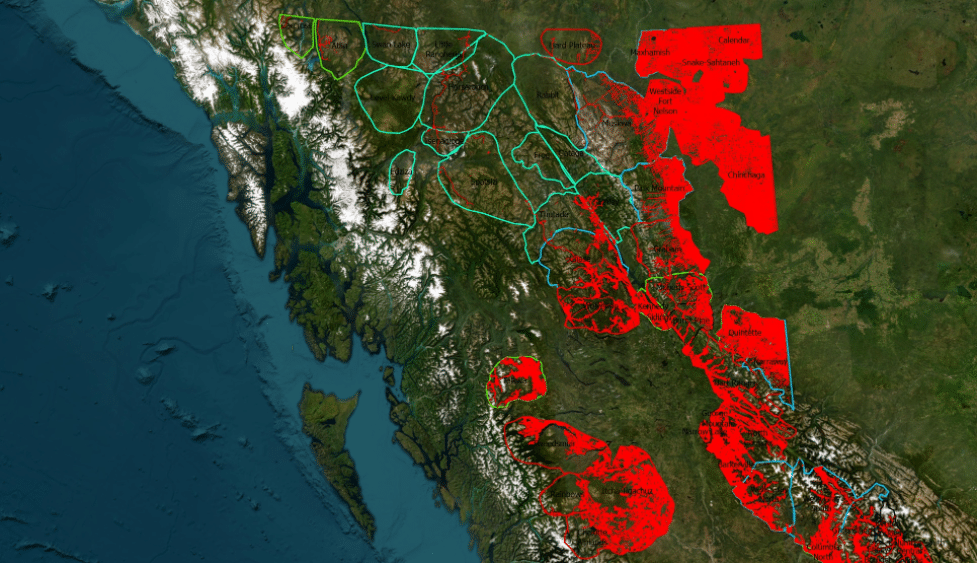

The Province continues to allow logging and fragmentation of critical habitat in endangered caribou herd areas while scapegoating wolves as the culprits of the caribou’s decline. GIS mapping analysis shows that 136,229.07 square kilometres of habitat have been lost within caribou herd ranges due to human disturbances. This is equivalent to 86 million hockey rinks or almost 47 times the footprint of the lower mainland. This habitat loss has actually steadily increased since provincial and federal governments were tasked with caribou recovery in 2003. Without protecting and restoring the old-growth forest that caribou depend on, the wolf cull is at best a “palliative measure”[xvii] for the dwindling herds, and stalls the push for true protective action. Therefore, at Pacific Wild, we believe caring about wolves IS caring about caribou.

Photo Mark Williams

WHY HABITAT?

Woodland caribou populations have undergone severe declines in B.C. since the turn of the 20th century. The Caribou recovery strategy (2014) states that “at the turn of the 20th century, the estimated number of caribou in all of BC was 30,000-40,000 (Spalding 2000). Aboriginal traditional knowledge holders stated that prior to the arrival of Europeans in north-eastern BC, caribou populations were so high that they were described to be “like bugs on the land” (Willson 2014). Historical records and more recent survey information suggest a general declining trend until about the 1940s, followed in some cases by an increase in numbers through to the 1960s, a subsequent decline in the late 1970s, an increase in the mid-late 1990s, and a decline to the present (Bergerud 1978, Stevenson & Hatler 1985, Seip & Cichowski 1996, Spalding 2000, Thomas & Gray 2002).“According to federal designations, the boreal ecotype is classified as threatened, the northern mountain ecotype as special concern, and the central and southern mountain ecotypes as endangered, with eight local population units under imminent threat.[i] The B.C. Conservation Data Centre (CDC) has identified the northern mountain ecotypes as blue listed (species of special concern), while the boreal and southern mountain ecotypes are red listed (species that are extirpated, endangered or threatened).[ii]

FORESTS ARE FOOD

The decline of caribou is one of the toughest conservation challenges in North America. In B.C., caribou are facing a crisis due to habitat destruction. Woodland caribou are food specialists; they depend on old-growth forests that provide abundant lichen as their primary food source. However, human activity has destroyed, degraded, and fragmented caribou habitat. Industrial logging, mining, oil and gas extraction, and recreational activities have rendered the land incapable of sustaining caribou populations.

Caribou face overwhelming health stressors as a result of severe nutritional inadequacies and disease stemming from habitat loss.[iii] As caribou are unable to meet dietary requirements for protein and energy, they exhibit suppressed maternal body fat as well as calf production and growth.[iv] These widespread health issues make caribou in B.C. susceptible to disease, parasites, and predation.[v,[vi],[vii] Starvation resulting from the destruction of old-growth forests has had a devastating impact on the reproduction, growth, and survival of caribou populations.

HABITAT LOSS COMPOUNDS PREDATION

When old-growth forests are cleared, they are replaced by early seral forests, which consist of more open, early‐successional vegetation and shrubs. This type of open habitat is favoured by moose, elk, and deer, which move into historically caribou habitats as these landscapes are changed by humans. Moose, elk, and deer are the primary prey of wolves, which follow their preferred prey into the altered landscape through linear features such as logging roads, seismic lines, and snow-packed trails. Although primary prey species don’t directly compete with caribou, their abundance creates a secondary pressure on the species by supporting higher wolf populations, which increases wolf-caribou encounters and predation. The interaction is ecologically termed “apparent competition.”[viii] Wolves don’t normally seek out caribou, but an exposed caribou will suffice as a meal when they are searching for their primary prey. Simply put, caribou become the wolves’ by-catch. Humans are the ultimate cause of these changes in predator-prey dynamics.[ix]

Wildlife researchers aim to understand the dominant mechanism by which wolf-caribou co-occurrence is facilitated. In addition to the apparent competition hypothesis leading to wolf-caribou spatial overlap, some research shows greater support for the direct effects of linear features on caribou-wolf, co-occurrence (and thereby predation) [x],[xi] DeMars and Boutin’s 2018 study demonstrated that networks of linear feature extending throughout areas of bog habitat increased predator selection for bogs, a habitat type typically favoured by boreal caribou for refugia. The use of these linear features by female caribou increased mortality of new-born calves.[xii] Female caribou with calves did avoid the use of linear features and areas with a high density of linear features, presumably due to predation risk, however the study found that most caribou were unable to completely avoid exposure to linear features.[xiii] The findings illustrate how linear features diminish prey refugia.

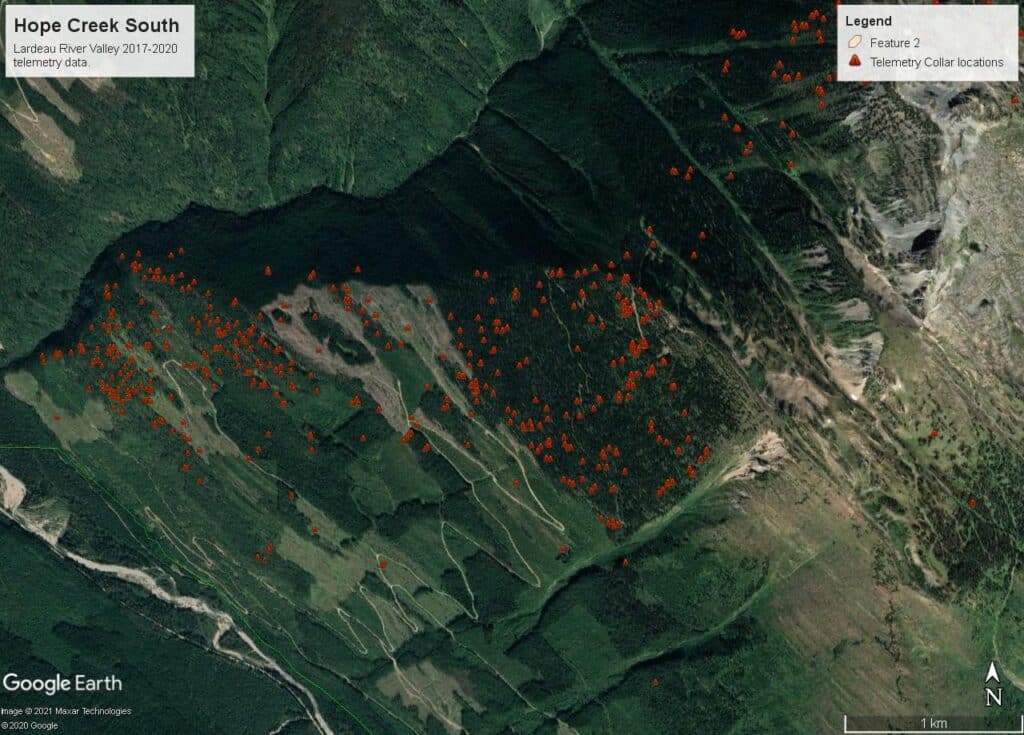

Telemetry mapping by the Valhalla Wilderness Society illustrates that radio-collared caribou by Hope Creek in the Central Selkirk herd range prefer mature and old-growth forests rather than clearcuts and young forest (see image below). Logging access roads allow predators to trap caribou in the remnant patches of mature forest, greatly enhancing the success of predators such as wolves while severely diminishing the chances for caribou to escape.

Scientists refer to the human-mediated predation of caribou by wolves as a proximate cause of decline, or a top-down pressure. However, experts are in agreement that the bottom-up forces associated with habitat loss represent the ultimate cause of decline and herd extinction. Human disturbance means caribou have nothing to eat and nowhere to hide. In addition, the cumulative effects from all forms of industrial development,[xiv] forest fires, the mountain pine beetle, and climate change all increase pressure on woodland caribou.[xv]

Image: “Caribou have nowhere to hide.” This telemetry map shows the distribution of radio-collared caribou by Hope Creek in the Central Selkirk herd range. The red telemetry markers of collared caribou in this satellite image from Google Earth shows that caribou prefer mature and old-growth forests rather than clearcuts and young forest. See how the red markers are denser in the darker green (older forest) and very scarce in the grey-brown (recently clearcut) areas. Note how all the logging access roads allow predators to trap caribou in the remnant patches of mature forest. This type of habitat destruction greatly enhances the success of predators such as wolves while severely diminishing the chances for prey animals to escape. Image and analysis courtesy of the Valhalla Wilderness Society.

short term solutions: mitigating predation

Apparent competition and the direct effects of linear features are likely both contributing to increased wolf-caribou overlap in many cases. Regardless of the dominant mechanism leading to caribou-wolf co-occurrence, which may vary by herd range, the altered landscape and access facilitated through linear features lead to the decline of caribou populations. A growing subset of scientific literature is dedicated to solutions that block linear features and restore previous landscapes.[xvi],[xvii],[xviii],[xix],[xx],[xxi]

Functional restoration involves deactivating linear features such as forest service roads and seismic lines to render them impassable. Felling trees across seismic gas line corridors, and creating swales and debris piles are techniques that have been assessed to slow travel by predators on human-created features on the landscape. It also has the effect of naturally moving wolves’ preferred prey species (moose, elk, deer) away from caribou herds. Refugia for caribou becomes more isolated and secure, and spatial overlap more characteristic of pre-disturbance. Experiments in functional habitat restoration have shown that by deploying obstacles to disrupt ease of movement on human developments, wolf-caribou encounters were reduced by 85%.[xxii] Functional habitat restoration offers short-term results while long-term ecological restoration progresses.

Scientists refer to the human-mediated predation by wolves as a proximate cause of decline, or a ‘top-down’ pressure. However, experts are in agreement that the ‘bottom-up’ forces associated with habitat loss represent the ultimate cause of decline and herd extinction. Regardless, human disturbance means caribou have nothing to eat and nowhere to hide. In addition to the cumulative effects from all forms of industrial development, further cumulative impacts from forest fires, mountain pine beetle, and climate change all add up to exert mounting pressures on woodland caribou.

Scapegoating Wolves is a “Palliative Measure” Distracting from Habitat Destruction

The B.C. government has yet to adequately address habitat loss. Instead, it has aimed to intensively reduce the population of wolves through aerial gunning and the use of “Judas wolves,” a controversial practice by which individual wolves are collared with GPS trackers to lead contracted aerial shooters back to their packs. However, there is a lack of reliable science to indicate that the reduction of wolves is having a meaningful impact on caribou recovery.[xxiv],[xxv],[xxvi] Habitat loss has only intensified since the cull began, despite caribou being listed as an at-risk species under federal legislation and provincial commitments to protect critical caribou habitat.[xxvii],[xxviii],[xxix],[xxx]

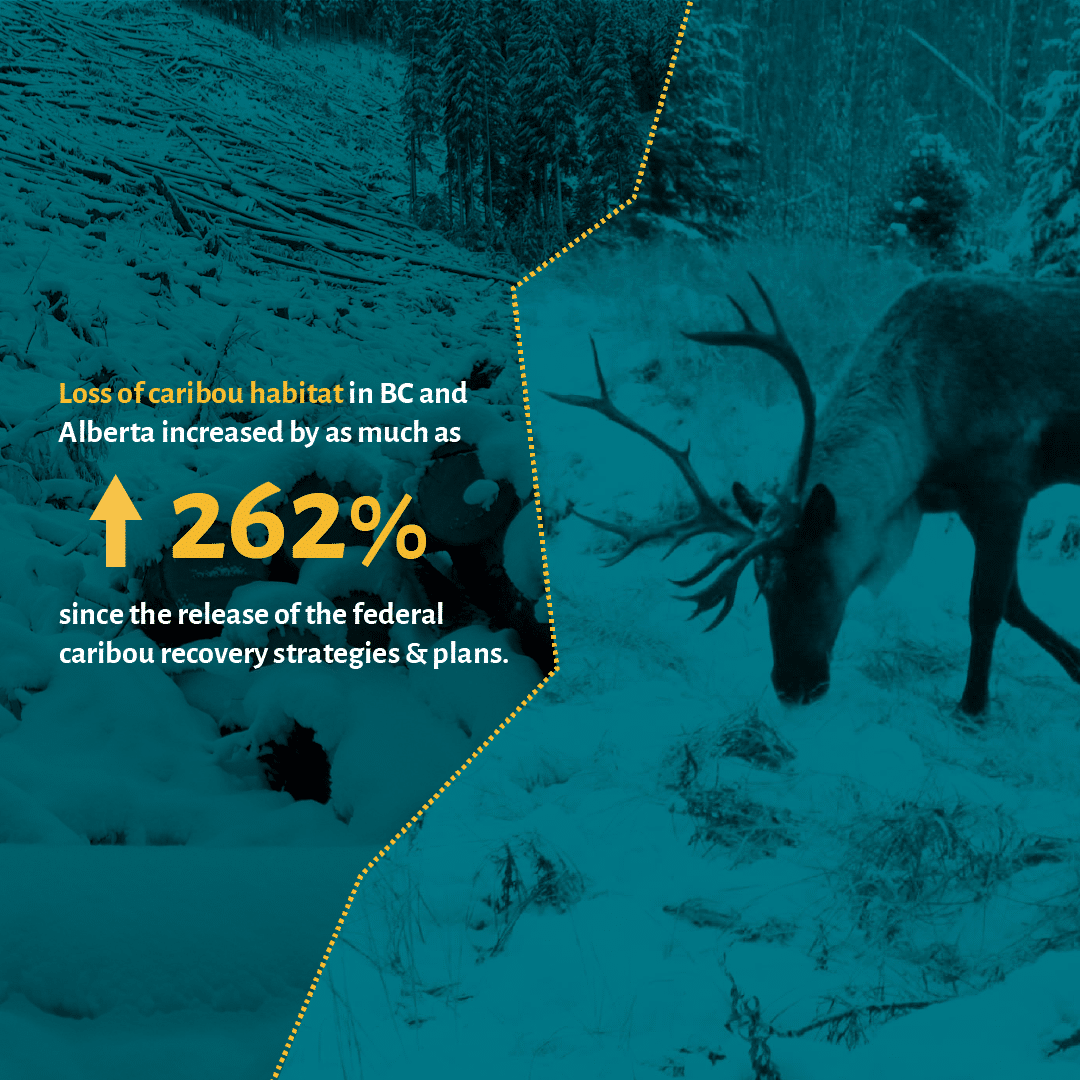

Federal recovery strategies and management plans for woodland caribou released in 2012 and 2014 specify that undisturbed habitats are necessary to achieve self-sustaining populations. Under the 2002 Canadian Species at Risk Act (SARA), which mandates the protection and recovery of endangered or threatened species and their habitats, the development of action plans is mandatory to specify the approach for achieving critical habitat conservation and recovery objectives over time.

A 2021 study conducted by multiple researchers including lead scientists from Environment and Climate Change Canada evaluated the effectiveness of environmental policy through an analysis of forest cover. Their report demonstrated that the rate of habitat loss is accelerating despite federal policy instruments. Notably, the study showed that loss of caribou habitat in B.C. and Alberta had increased by 262% in the six to seven years after the release of the federal recovery strategies and management plans.[xxxi] The researchers concluded that federal policy commitments do not necessarily translate to implementation of commitments, in part due to the lack of species-at-risk legislation outside of federal lands.

In general, Canada has been ineffective in recovering caribou habitat and herds due to gaps between listing, recovery planning, and the execution of conservation and restoration. Mariana Nagy‐Reis, the lead author of the study, drew the following conclusions:

“Our findings support the idea that short-term recovery actions such as predator reductions and translocations will likely just delay caribou extinction in the absence of well-considered habitat management.”

“Predator reductions are a palliative measure as caribou populations are prone to returning to decline soon after such actions cease. Further, it is likely that effective predator management would become increasingly difficult, or impossible, as landscape alteration increases.”

“Our study suggests that unless human-related habitat alterations are adequately addressed, the recovery of most woodland caribou populations seems unlikely.” [xxxii],[xxxiii]

Scientists resoundingly assert that the cumulative impacts to the land must be addressed to achieve self-sustaining caribou populations. Long-term commitments, including reduction in habitat degradation and restoration, are imperative.

Visualising Caribou Decline and Habitat Destruction

The following graphs, videos, info graphics and maps illuminate the extent of increasing habitat destruction overtime in critical caribou habitat.

These timelapse videos use data layers from a larger GIS map (explorable below) to show the changing landscape of caribou herds between 1950 and 2022 across British Columbia, and also a case study of the George Mountain and Narrow Creek caribou herds in particular between 1984 and 2022.

Timelapse: Caribou Habitat Destruction in BC 1950-2022

Timelapse: Case Study of Narrow Lake & George Mountain Herds

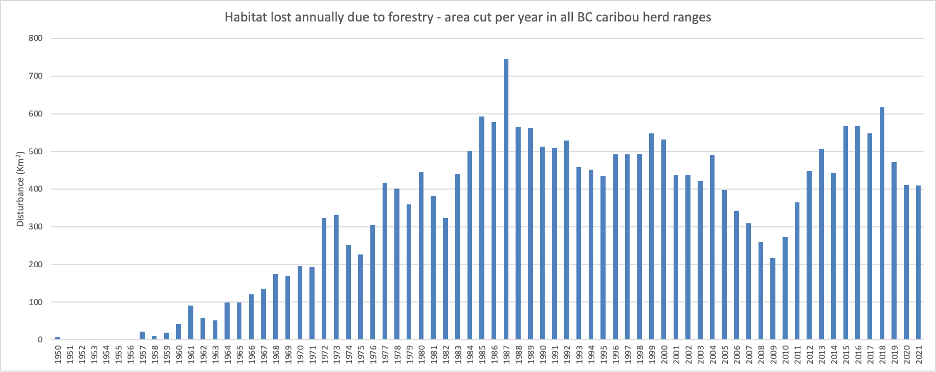

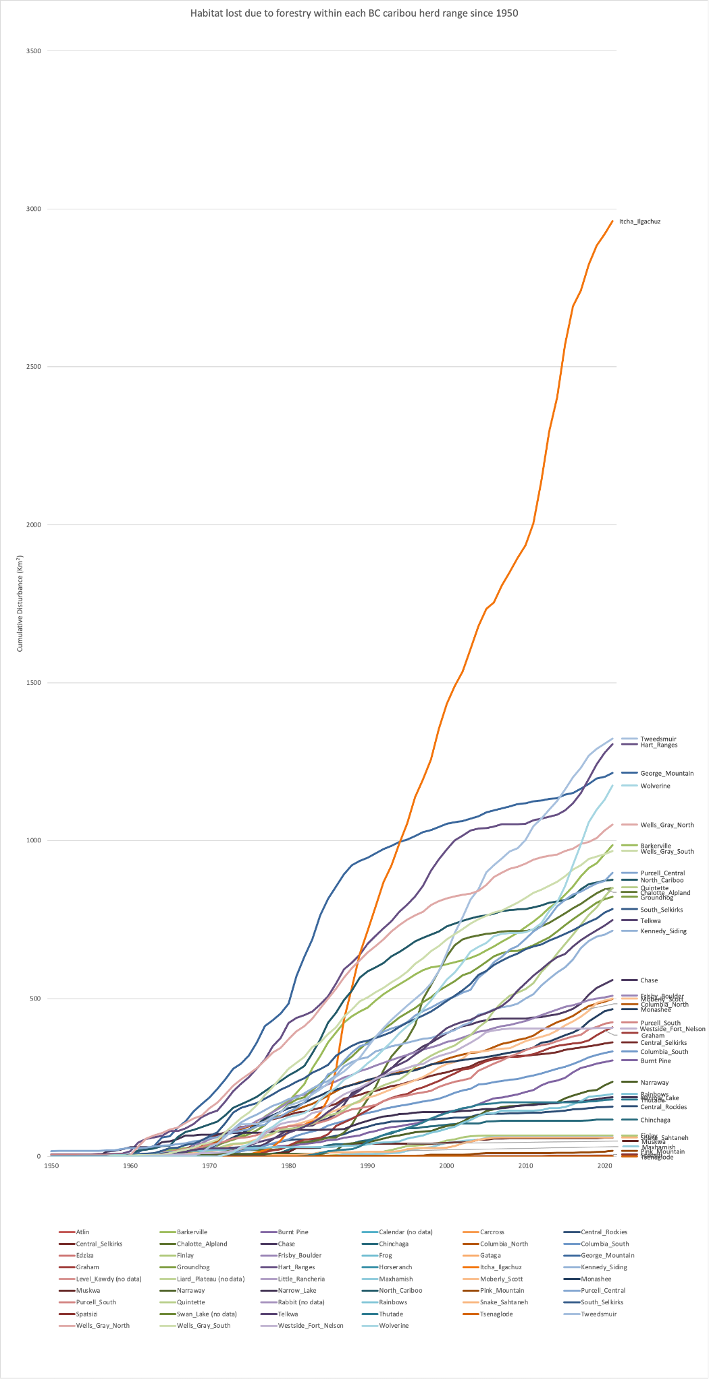

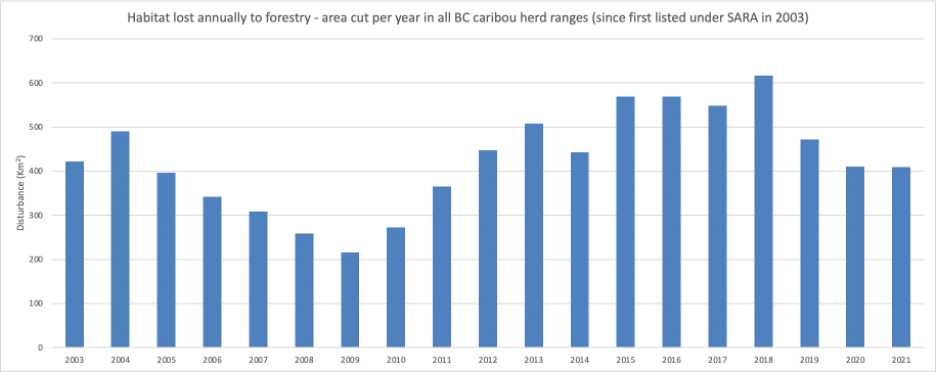

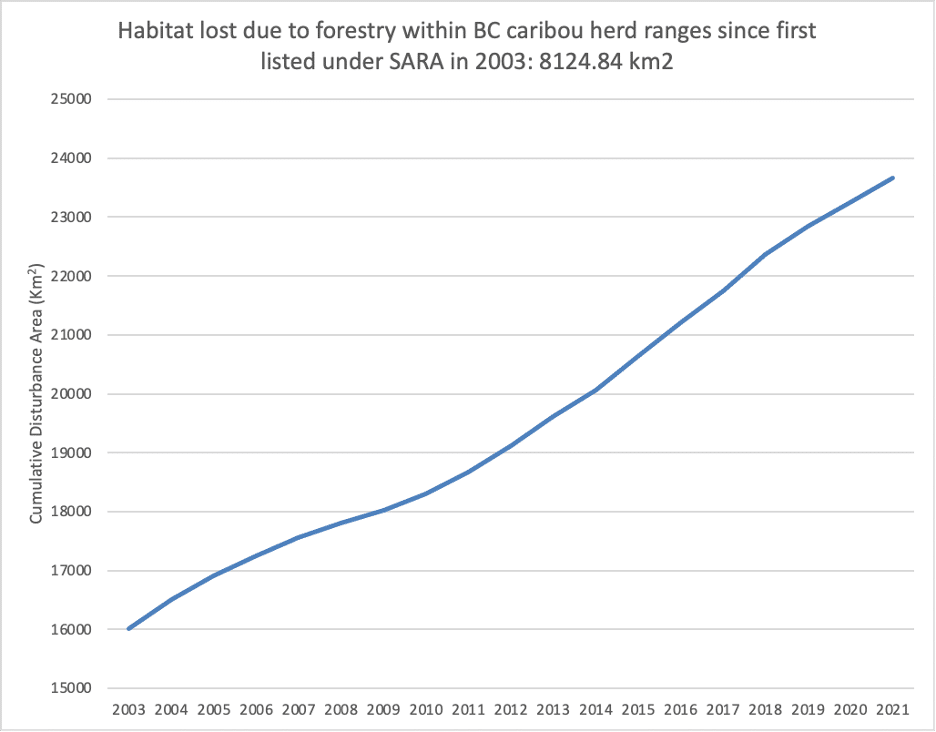

Caribou Habitat Loss Due to Forestry in B.C. Over Time

Images: Pacific Wild conducted comparative spatial analysis on habitat disturbance using compiled government data on the distribution of caribou herds, grey wolves, and extractive resource practices from 1900–2022. Our researchers downloaded publicly-available forest practice datasets from B.C.’s spatial data portal and plotted them against distribution and abundance data for caribou herds illustrated in B.C.’s wildlife management plan report. By comparing the distribution of caribou herds and the annual forest cut block dataset, we can clearly see patterns of habitat extraction from caribou herd territories accelerating despite caribou being listed as an at-risk species.

Interactive Map: Explore Caribou Herd Ranges and Disturbance by Extractive Industries

Explore this interactive map to see how caribou populations, habitat disturbance, and estimated wolf densities overlap.

Forest Cuts in Hockey Rinks

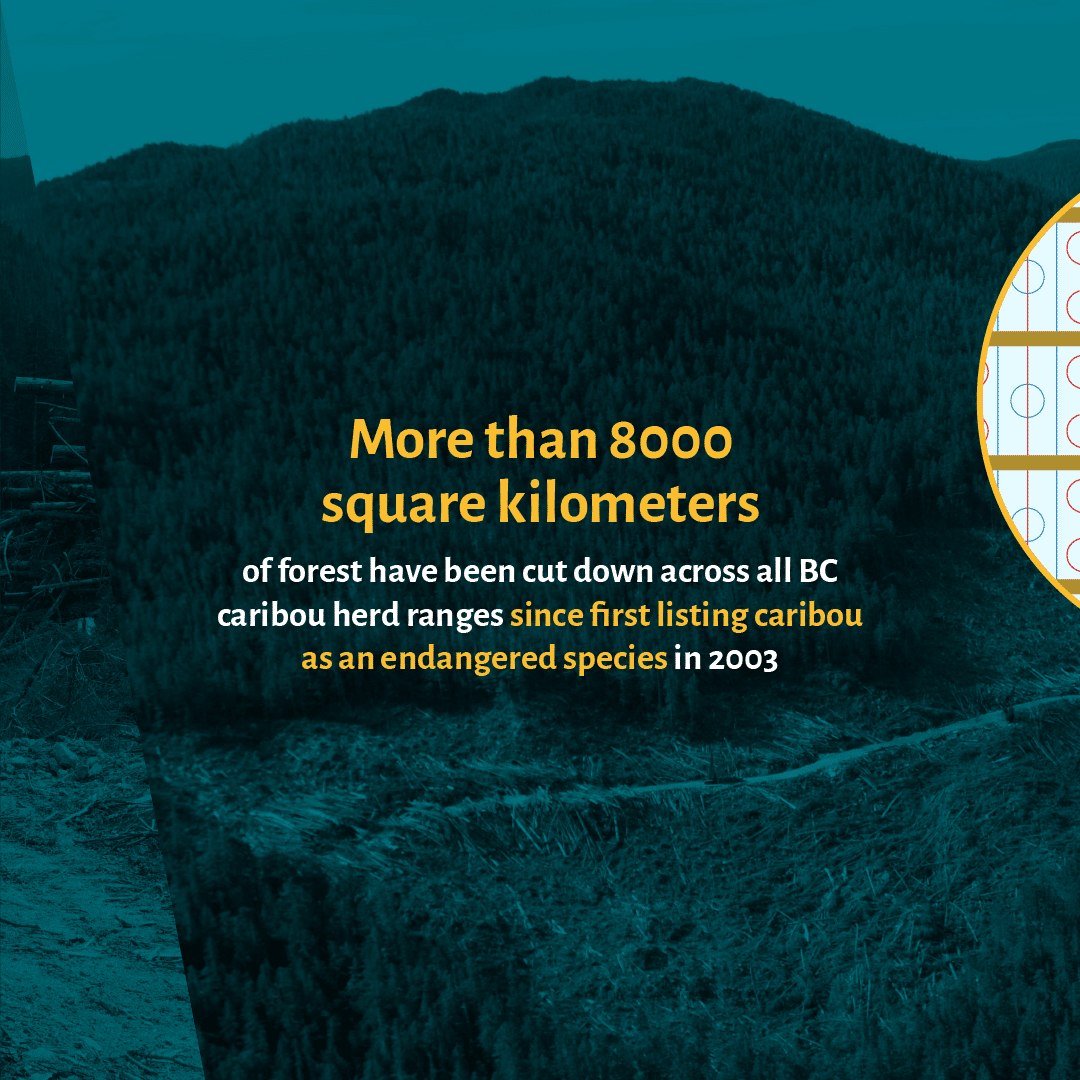

How many hockey rinks of habitat within caribou herd ranges have been cut for forestry alone? The NHL’s official ice hockey rink measures 85 by 200 feet (25.91 by 60.96 metres) for a total area of 17,000 square feet or 0.0015793517 square kilometres. Over 23,718.58 square kilometres of habitat has been destroyed by forest practices alone.

15,593.74 square kilometres of forest were lost before the caribou were first listed under SARA in 2003. A further 8124.84 square kilometres, or one third of the total disturbance of forest, have been cut down across all B.C. caribou herd ranges since that year. In total more than 5 million ( 5,144,415 ) hockey rinks of forest have been removed since 2003 alone. That is equivalent to 2.8, almost three times the footprint of the lower mainland from Lions bay to Langley (2,878.93 km2).

The charts below show that cumulative habitat loss (from forestry alone) has increased steadily since the caribou were listed as a species-at-risk. We would like to see this curve plateau indicating minimal new forest cut disturbance. Since the current wolf cull program began in 2015, habitat destruction in the form of logging alone has not been adequately addressed.

Forestry Data Limitations:

In total, at least 23,718.58 square kilometres of habitat have been lost within B.C. caribou herd ranges due to forest practices alone. However, as this total is only based on available data, it is likely a significant underestimate. For most herds, annual cut data is available after 1950, but data on some herds is only available for the past few years. Five herds don’t have any data at all. Moreover, the data only covers disturbances from forestry practices. It does not include disturbances from new linear features nor the oil and gas development that is responsible for much of the impact on caribou habitat in north-western B.C.. Finally, the disturbance area quantified does not include a buffer of 500 metres as specified by Environment Canada’s recovery strategies[i],[ii] and consistent with current research[iii]. Taken together, data availability, forestry disturbance focus only and nonapplication of a justified 500 metre buffer mean that this estimate does not account for a significant proportion of disturbance and is therefore a bare minimum of the total area disturbed.

The full impact: comprehensive habitat loss

In order to present a comprehensive picture of disturbance, we carried out further geospatial analysis of total disturbance within B.C. caribou herd ranges. This analysis calculated the total area of disturbance from combined impacts of forestry, mining and oil, roads, and urbanisation using open data from Open Government (Government of Canada)[iv] and British Columbia Human Disturbance Data Explorer[v]. In addition, a disturbance buffer of 500 metres was applied to account for the zone of influence (caribou avoidance). The 500 metre buffer is defined as part of disturbed habitat within Canada’s recovery strategies.[vi],[vii] Note, however, that usage of this buffer width was adopted and implemented as a ‘minimum approximation’.[viii] Indirect habitat loss due to caribou avoidance of human infrastructure was found to be significantly greater in a study focusing on northern mountain caribou; ranging from one to nine kilometres depending on season and development type (e.g., roads, towns, mines, or cabins).[ix]

Based on the analysis, the total disturbance within caribou herd ranges is 5.74 times that of forestry alone! Specifically, 136,229.07 square kilometres of habitat has been lost within caribou herd ranges due to human disturbances.

How many hockey rinks of habitat within caribou herd ranges have been lost to human disturbances? Over 136,229.07 square kilometres of habitat has been impacted by humans . This is equivalent to 86,256,324 hockey rinks (compared to 15,017,924 for forestry alone), almost 47 times the footprint of the lower mainland metro Vancouver area.v

86 million hockey rinks of habitat loss

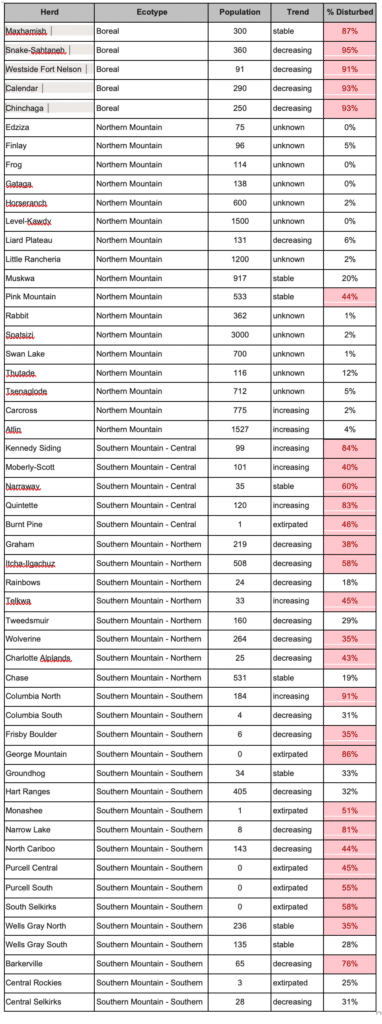

Habitat Disturbance by Herd: Exceeds the Recovery Threshold

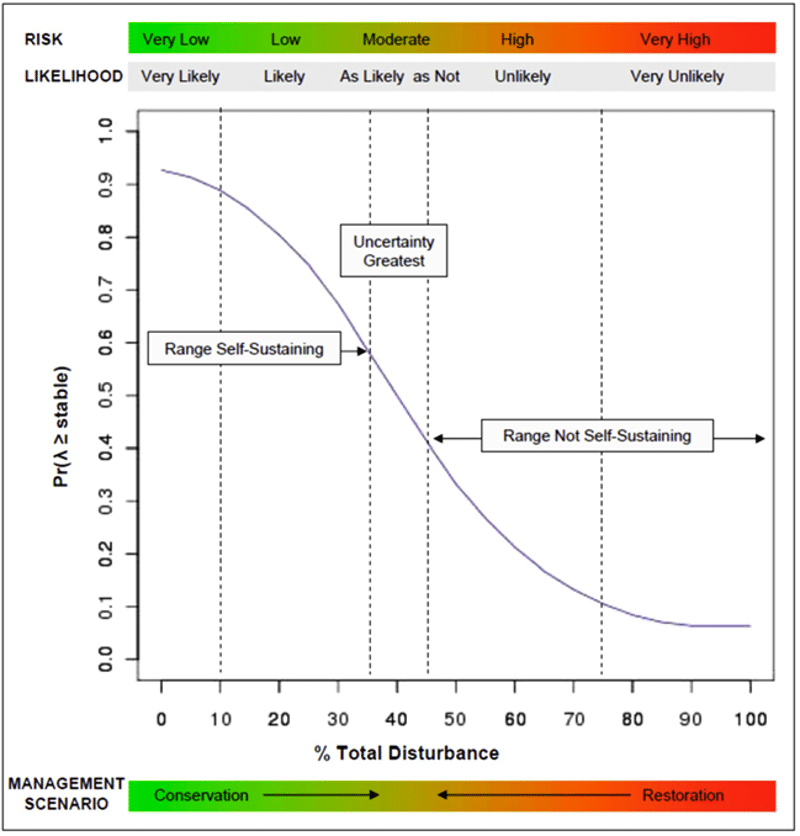

Habitat disturbance exceeds the range-scale federal recovery threshold in 27 out of 52 (52%) caribou ranges in B.C (see table below). The disturbance threshold set out in the National Recovery Strategy for Woodland Caribou, Boreal Population[x] was identified as “65% undisturbed habitat in a range as the disturbance management threshold, which provides a measurable probability (60%) for a local population to be self-sustaining. This management threshold is considered a minimum threshold because at 65% undisturbed habitat there remains a significant risk (40%) that a local population will not be self-sustaining.” One study suggests the boreal 65% undisturbed habitat threshold may be a reasonable proxy but some herds may be more vulnerable due to cumulative pressures like fire and climate change.[xii] Therefore, achieving higher than the minimum requirement is essential to improving caribou resilience to climate change.

While the recovery strategy for the Southern Mountain Population [xii] adopted the 65% threshold for identifying specific types of critical habitat for the Northern and Central Groups of the Southern Mountain ecotype, no comparable threshold has been developed specifically for the Southern Mountain or Northern Mountain ecotypes, as with the Boreal ecotype. However, with data from our geospatial analysis, we are able to compare disturbance levels in all herds to the boreal threshold of 65% undisturbed habitat (equivalent to 35% disturbed).

All boreal herds are under severe threat, as indicated by the disturbance levels ranging between 87-95%, well above the threshold of 35% disturbance indicating the likelihood of those populations being self-sustaining as ‘very unlikely’ (see figure below). The majority of Southern Mountain herds also exceed 35% disturbance within their ranges and are unlikely (and in some cases very unlikely) to be self-sustaining.

Caption note: There are differences from our data in the literature. This may be due to differing map outlines/shape-files for area of herd range boundaries or methods of calculating total disturbance.

Caption: Management threshold for disturbance. “The probability of observing stable or positive growth (λ ≥ stable) of boreal caribou local populations over a 20-year period at varying levels of total range disturbance (fires ≤ 40 years + anthropogenic disturbances buffered by 500 m). Certainty of outcome, ecological risk, and management scenarios are illustrated along a continuum of conditions.” Adopted from Environment Canada (2011)[xiii]

Our analysis on habitat loss and disturbance percentages within ranges clearly shows why caribou herds are declining across B.C. Habitat destruction leads to caribou declines as caribou need habitat to survive and maintain self-sustaining populations. Even if caribou populations were to increase as a result of temporarily reduced predation pressure from wolf culls (pressure that arises from altered habitat), where would they live without their habitat? Caribou population growth would then be falsely inflated and not supported or sustained by healthy habitat requirements. Habitat loss (diminished quality or quantity) means that the carrying capacity of species occupying the ecosystem are lowered, so that populations decline often to extinction. Since caribou were first listed under SARA in 2003, seven herds of Southern Mountain Caribou have become extirpated (locally extinct): Central Rockies, George Mountain, Monashee, Purcell Central, Purcell South, South Selkirks, and Burnt Pine. Habitat protection and restoration, especially evidence-based shorter-term solutions like disrupting linear features[xiv],[xv], are a necessity for caribou survival.

WHO PAYS?

Taxpayer dollars fund the wolf cull

Lethal wolf control is touted as a short-term recovery action by the B.C. government, which acknowledges that habitat is a key issue for protecting the herds. Proponents of the government predator control program have stated that the wolf cull will need to be maintained until habitat is restored.[i],[ii] Meanwhile, resource extraction continues in herd areas and restoration efforts are critically underfunded.

At the quarterly caribou recovery stakeholder meeting in January 2023, estimated that it would take 40 years for forests to ‘recover’, assuming no further habitat is removed.[iii] Estimates in the scientific literature are more conservative and indicate that lichens, an essential food for caribou, can take 60-90 years to regenerate post-disturbance.[iv] Some estimates are greater than 100 years.[v]

Eight years into the cull, it is clear that intensive wolf reduction has become a long-term endeavour with short-term results which masks continued and significantly increasing habitat removal and fragmentation, and will lead to the demise of additional caribou herds.

How much is it costing taxpayers?

The wolf cull program has cost British Columbians over 10 million of dollars to date. To assess the efficacy of the program and help taxpayers understand how their money is being used, the government should release detailed reporting on the allocation of public funds for the wolf cull. However, based on various reports and piecemeal information provided by the provincial government,[vi],[vii],[viii],[ix] the total cost since 2015 is estimated at $10.1 million.

Wolves are paying for these policies with their lives

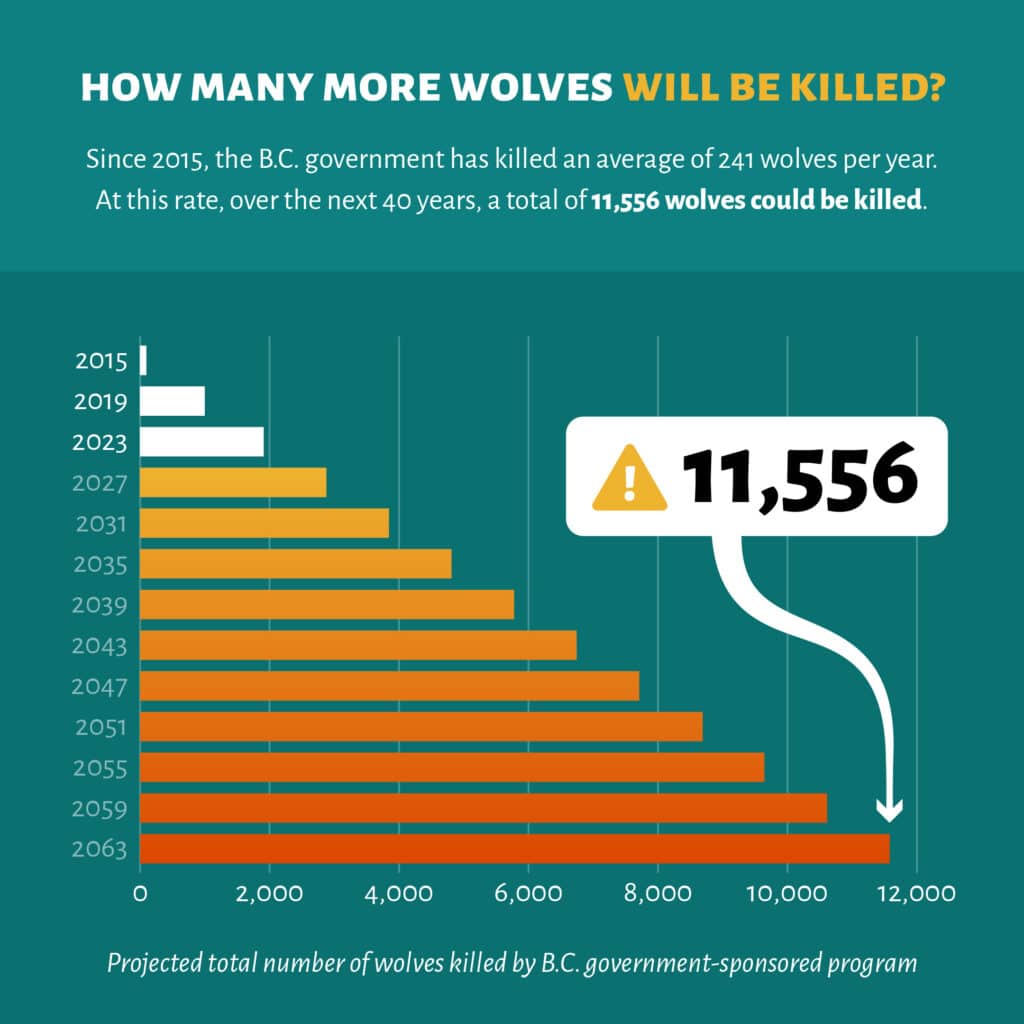

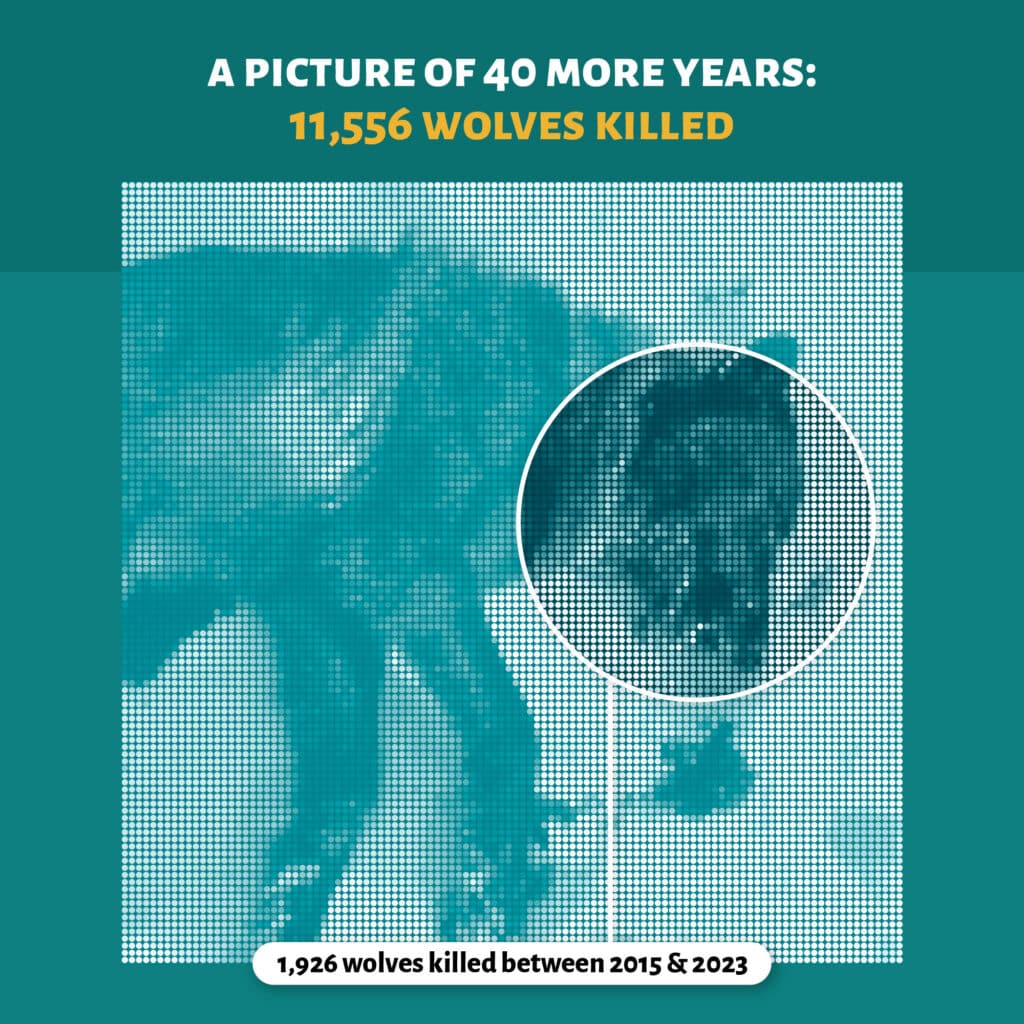

Records indicate that 2,192 wolves have been killed since the aerial culling program (shooting wolves from helicopters) began in 2015. Hunters funded by the B.C. government kill an average of 243 wolves each year. If the wolf cull were to continue for the 40 years that the B.C. government estimates are needed to restore caribou habitat, then approximately 11,556 wolves would be killed by 2063. The long-term impact on predator-prey relationships by a cull program of this magnitude and persistence will cause unintended ecological consequences[x],[xi],[xii] and still not address the root cause of caribou extirpation. This figure assumes that no further habitat is altered. With resource extraction steadily increasing, the number of wolves on the landscape will likely increase as well, making an effective cull exceedingly difficult.

HOW MANY MORE WOLVES WILL BE KILLED?

Current Total and Projections

Since 2015, the cull has cost an average of $1,130,554 per year. Assuming that it continues for another 40 years, and accounting for 3.5% annually-compounded interest, B.C. taxpayers will have spent $101,120,723 on wolf killing by 2063. The opportunity cost of continuing the wolf cull for another 40 years is over 100 million dollars.

WHO'S IN CHARGE?

In 2002, federal species-at-risk legislation was enacted, known as the Canadian Species at Risk Act (SARA)[i]. This legislation mandates the protection and recovery of extirpated, endangered or threatened species and their habitats. Boreal caribou are listed under SARA as threatened, central and southern mountain ecotypes are listed as endangered.

Under SARA, the federal government is responsible for identifying critical habitat and for the preparation of recovery strategies, action plans, and progress reports for listed SARA species.[ii] However, SARA only applies automatically to federal lands, aquatic species, and migratory birds. B.C. is comprised of just 1% federal crown land,[iii] and so only a very small fraction of wildlife is protected under SARA.

Even though woodland caribou are federally designated as threatened and endangered, there are no specific legal protections for the species on provincial lands in B.C..[iv],[v] Management of listed Canadian species with habitat across provincial lands (like caribou), and wildlife management in general, is under the jurisdiction of the Province.

No provincially dedicated species-at-risk legislation

So then, what legislation does B.C. have to protect woodland caribou? Unlike most provinces, B.C. does not have provincially-dedicated species-at-risk legislation, representing a major void in any provincially-led policy to protect imperilled species. The provincial government undertakes planning and reporting through the provincial Caribou Recovery Program,[vi] but the only legislative tools available to land managers in B.C. to support habitat conservation and caribou recovery are some combinations of the Land Act, Wildlife Act, the Forest and Range Practices Act, the Oil and Gas Activities Act, and the Environmental Protection and Management Regulation for petroleum and natural gas activities.[vi],[vii] All of these pieces of legislation are intended for some other purpose (such as development or hunting) and none constitutes a stand-alone law with the intent of protecting endangered species.

The most pertinent provincial law, the Wildlife Act, is outdated and does not offer species-at-risk protection measures for caribou and their habitat. Only four species were designated under the Wildlife Act in 1980 (three endangered, one threatened): the Vancouver Island marmot, the sea otter, the American white pelican, and the burrowing owl. No animals have been added to the Act since, even though the British Columbia Conservation Data Centre has identified 1909 candidate species-at-risk.[ix],[x] There is no single piece of legislation specifically designed to protect caribou and critical habitat.[xi] Without provincially-dedicated species-at-risk legislation, threatened and endangered species stand little chance when facing off with resource industries.

Tools for federal intervention

In cases where provinces are not adequately meeting mandated goals and timelines, the federal government can intervene. Under Section 80 of SARA, the Canadian Minister of Environment can recommend an emergency order to halt any activities, regardless of location, that cause further harm or degradation of habitat. In fact, the Minister is obligated to intervene if they are “of the opinion that the species faces imminent threats to its survival or recovery.”[xii] However, Cabinet makes the final call to issue an order.

Emergency order recommended under SARA

In 2018, the Minister of the Environment decided that southern mountain caribou were facing imminent threats to recovery and recommended an emergency order to provide protection. In March 2021, the Government of Canada released a decision acknowledging the imminent threats to the caribou, but declining the recommended emergency order.[xiii] The federal government outlined an approach to protect the caribou, which included:

- Federal funding

- Interim moratorium on new resource development enacted by the Province in parts of east-central British Columbia

- Intergovernmental Partnership Agreement for the Conservation of the Central Group of the Southern Mountain Caribou (February 2020)

- Canada–British Columbia Conservation Agreement for Southern Mountain Caribou in British Columbia (February 2020)

The final decision concluded that “The Minister will be closely monitoring the implementation of each of the measures described in this Statement. In appropriate circumstances, the Minister could make a new recommendation for an emergency order to provide for the protection of southern mountain caribou.” [xiv]

An emergency protection order has only been issued on two occasions: for the sage grouse and for the chorus frog.[xv],[xvi] Emergency orders are discretionary and decision-makers consider socio-economic implications.[xvii],[xviii] In the event an emergency protection order is advanced, the federal government is intervening in provincial decisions over resource development. In the case of the caribou, the Cabinet’s rationale for rejecting the emergency order alluded to respect for provincial jurisdiction.

Habitat degradation continues despite imminent threats

In the years since the federal government declined the emergency order, more critical habitat has been lost. In 2022, Adriana DiSilvestro reported that provincially-subsidised oil and gas activity occurred in critical habitat from 2019 to 2021, despite legal protections.[xix] Her research showed that the provincial wolf cull actually works to sustain the status quo of resource extraction since it satisfies intentions to take conservation action without addressing the root cause. The Province continues to choose industrial activities such as oil and gas wells, pipelines, clearcut logging, and mining over the protection and restoration of caribou habitat.

First Nations’ management and protection of caribou and wolf populations

In 2022, the Union of B.C. Indian Chiefs (UBCIC) passed Resolution 2022-09 calling for First Nations’ management and protection of caribou and wolf populations by territories.[xx] First Nations uphold the right to make decisions regarding land and wildlife management. Since the Province has repeatedly failed to restore habitat, remove linear features, and reduce development, the only option for many First Nations is to move forward with their own Caribou Recovery Plans. Resolution 2022-09 calls for a stop to unilateral state decisions on wolf culling and caribou recovery. While some First Nations are supportive of predator removal, UBCIC Resolution 2022-09 demonstrates that this support is not universal.

International Commitments spell positive steps for caribou

Canada has engaged in international commitments to halt biodiversity loss[xxi] and protect 25% of land by 2025 and 30% of land by 2030.[xxii] The Province agreed to meet these goals in December 2022.[xxiii] While the B.C. government’s past commitments to protecting critical caribou habitat have not materialised, there is hope. A first-of-it’s-kind $1 billion Tripartite Framework Agreement on Nature Conservation was signed by British Columbia (B.C.), the Canadian federal government, and Indigenous leaders in November 2023, with the goal of preserving biodiversity, protecting species and ecosystems at risk, and fighting climate change. This deal includes up to $500 million from both the federal and B.C. governments over eight years to meet conservation goals and protect 30% of land and water by 2030.

$50 million of this funding will also be allocated to protect old growth forest across B.C., and it comes on the heels of another major funding announcement: the $300-million Conservation Financing Mechanism to protect old growth and create protected areas in B.C.. The province is providing $150-million, which is being matched by the B.C. Parks Foundation for Indigenous-led stewardship and protection for important ecological areas with valuable old growth.

These are encouraging steps towards addressing the 14 recommendations of the Old Growth Strategic Review, and towards the protection of endangered species. However, no amount of funding will protect a forest once it has already been logged, and in October the province confirmed with the Penticton Herald that old growth logging has increased since 2020.

Immediate Concrete Action is Necessary to Protect Caribou

Scientific literature demonstrates that despite federal regulation and provincial commitments, we are still losing critical habitat at a significant rate. Conservation biologists and legal experts have called for effective species-at-risk legislation in B.C. and provided recommendations for success.[xxiv],[xxv] We have already lost thousands of caribou. Entire herds have been wiped out forever. At the fundamental level, the Province has not even ceased harmful activities within caribou habitat, let alone undertaken meaningful restorative actions. The Province continues to favour economics by permitting logging and other industrial projects in caribou habitat.[xxvi],[xxvii],[xxviii],[xxix] This is a dire situation that requires immediate federal intervention under SARA.

This resources list counters the Province’s claim that the wolf cull is science-backed and outlines the dire need to protect the woodland caribou’s critical habitat. It also shows that despite the B.C. government’s scapegoating of the grey wolf, the cull is unscientific, unsustainable, unethical, unacceptable, and unjust.

Chapter topics within the resources list include threats to caribou, Indigenous conservation, current wolf management, insufficient protection of caribou habitat, inadequate scientific evidence for the effectiveness of wolf control, unintended consequences of predator removal, preferred non-lethal methods, ethics research, and public disapproval. The document contains over 50 reference summaries from research articles, books, and government documents. It will be updated on a regular basis.

TAKE ACTION

Tell the federal government to step in to enact emergency habitat protection measures to save B.C. caribou before it’s too late.

Send a message to your MLA in B.C.

Tell your MLA you want an Endangered Species Act for British Columbia, and that habitat protection should be the number one action taken to protect caribou.

Speak up for wolves

Ask the federal government to stop issuing permits to shoot wolves from helicopters:

GET INVOLVED LOCALLY

Local conservation organizations

Land Use Planning Committees

Community Forest Boards

Speak Out Publicly

Image Jonah Keim, field researcher and project lead for functional habitat restoration in northeastern B.C.