Pacific Salmon Overview

Pacific salmon are anadromous, beginning their lives in freshwater (streams, rivers and lakes), then spending the majority of their lives in the ocean, before returning to their natal streams to spawn and die (PSF, 2017). This specialized behaviour and their ability to adapt to their changing environments has allowed salmon to maintain high genetic diversity. While it is not entirely understood how salmon manage to navigate thousands of kilometres back to their native streams, it is speculated that pheromones or geomagnetism play a part. This incredible feat allows them to travel upwards of 50 kilometres per day during their spawning migration.

Salmon are interdependent with other species within their ecosystems, interacting with other species of fish, feeding on zooplankton, and providing food for seabirds, bears, wolves, pinnipeds and whales. They are a vital part of the food chain, on which 127 species directly and indirectly rely. Salmon carry nutrients from their spawning streams to the oceans, and vice versa, fertilizing much of the Great Bear Rainforest. Due to their integral role in their ecosystems, salmon are labelled as a biosensor and are a brilliant indicator of general ecosystem health.

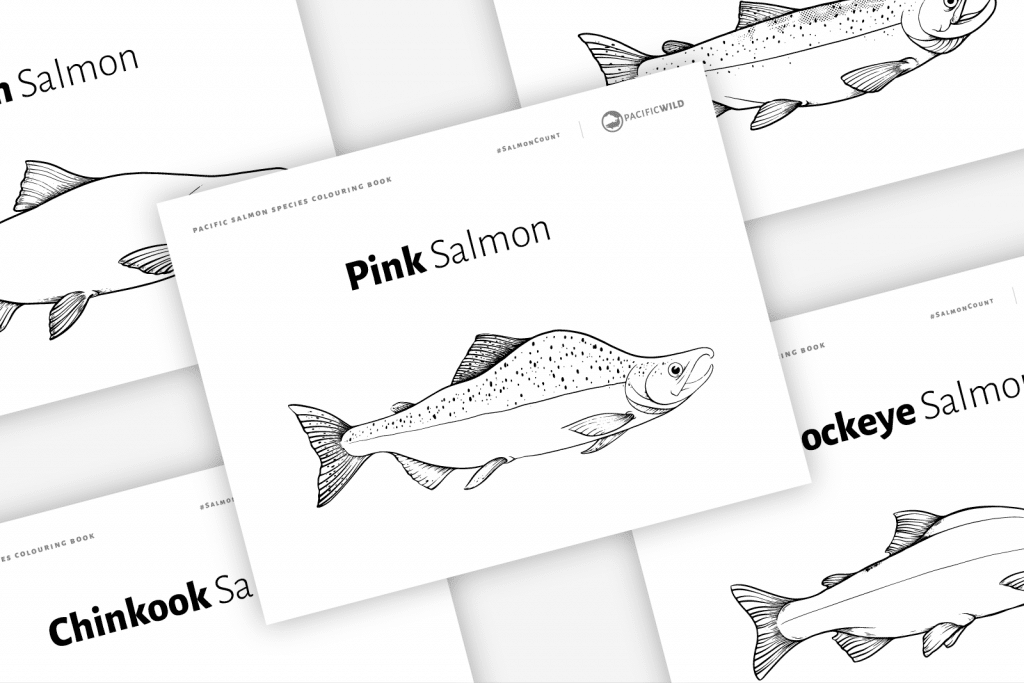

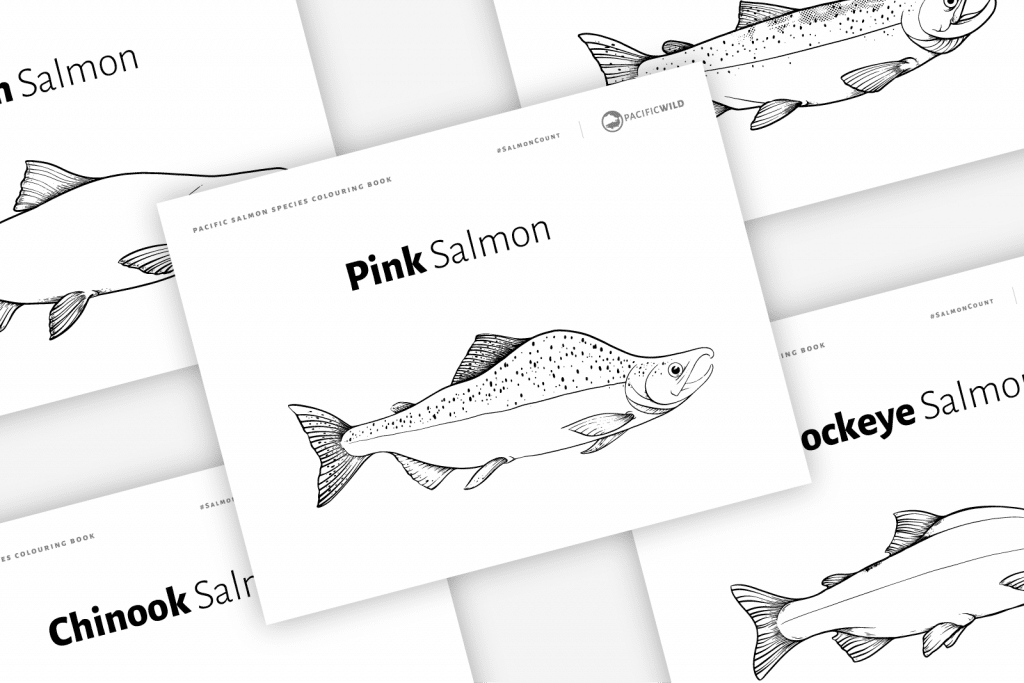

In British Columbia, there are over 9000 different populations (species and stream combinations) of salmon. There are five major salmon species making up the populations of the salmon fishery of B.C.: Pink (Oncorhynchus gorbuscha), Sockeye (Oncorhynchus nerka), Chum (Oncorhynchus keta), Chinook (Oncorhynchus tshawytscha), and Coho (Oncorhynchus kisutch). Each species, while equally essential to B.C. ecosystems, are very distinct in their migration patterns and spawning (Pacific Salmon Foundation).

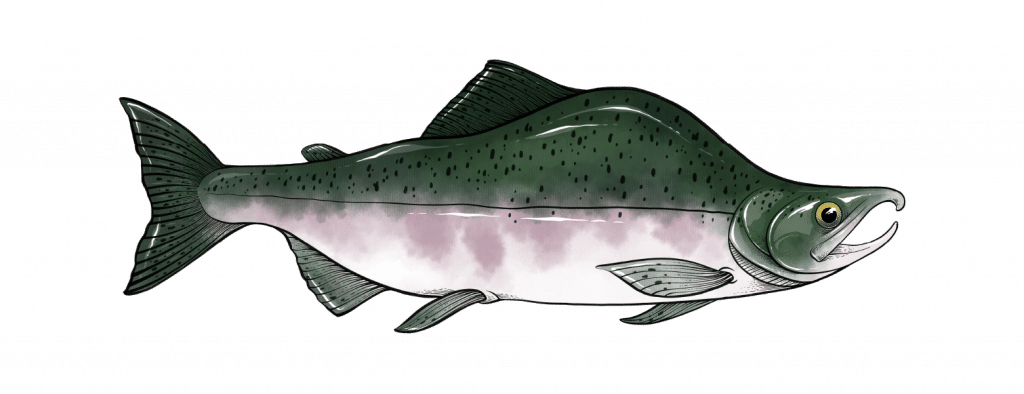

pink salmon

A.K.A. “Humpie” / Oncorhynchus gorbuscha

Pink salmon have silver-like skin with small scales and large black oval spots on their back and tail. Their nickname “Humpie” comes from the humped back they develop when spawning. They prefer shallow, calm rivers and creeks because they can’t jump as high as larger salmon species. Pinks have two distinct biennial populations: on the central coast of BC they return every odd year, whereas on the south coast they return every even year.

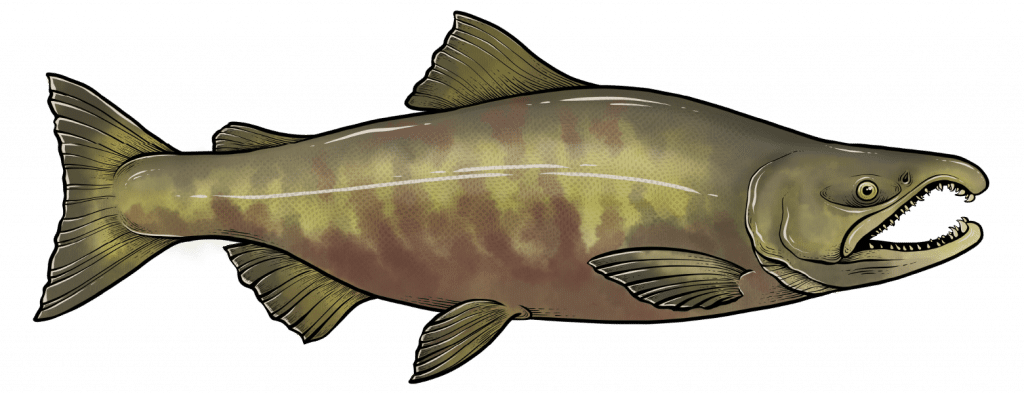

chum salmon

A.K.A. “Dog Salmon” / Oncorhynchus keta

Chum salmon are recognizable by their unique tiger stripe patterns and canine teeth they develop during spawning season. Chum are the last of the five Pacific salmon species to return to the creeks and rivers to spawn. They prefer shallow, calm waters as they are hindered easily by obstacles. Plankton, shrimp, krill, squid, and aquatic insects are amongst their favourite foods. Their low-oil flesh makes them ideal for cold-smoking, a common practice of coastal Indigenous Nations.

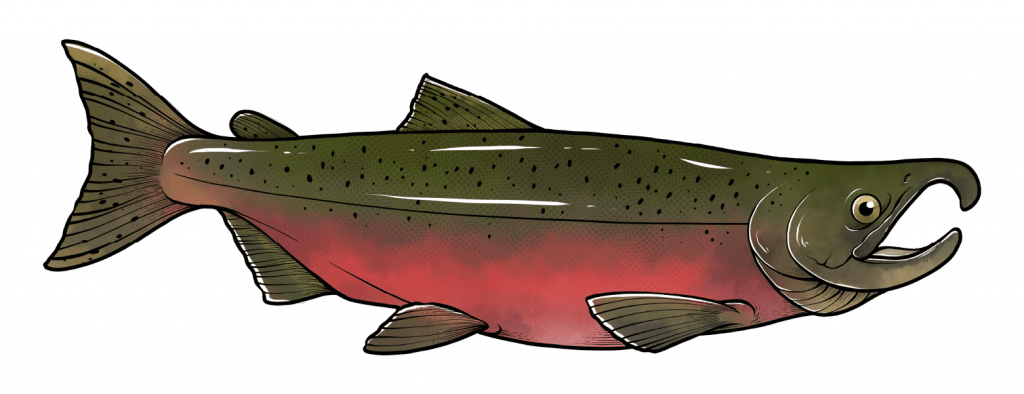

coho salmon

A.K.A. “Silver Salmon” / Oncorhynchus kisutch

Highly regarded for the acrobatic prowess, coho salmon make incredible journeys in their fight upstream. Leaping and twisting through the air, these iconic salmon make it past powerful currents, waterfalls, and rapids in their mission to spawn. During the ocean phase, they have distinctive deep blue colouring on their backs. When they return to the rivers to spawn, they develop reddish pink colouring on their sides and belly.

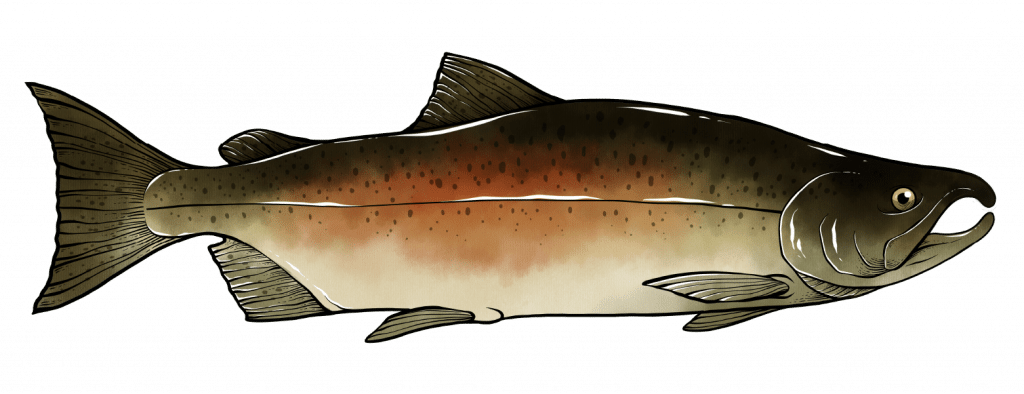

Chinook Salmon

A.K.A. Spring, King, Tyee / Oncorhynchus tshawytscha

Being the largest of the five Pacific salmon species, it’s no surprise that Chinook exhibit some of the most impressive feats of strength and endurance, sometimes travelling as far as 3,000 kilometres and climbing over 1,500m upriver. They have a silvery blue colouring during the ocean phase but this changes to an earthy, copper-black once they return to the creeks and rivers to spawn. The largest Chinook on record was a 57kg specimen caught in 1949 near Petersburg, Alaska.

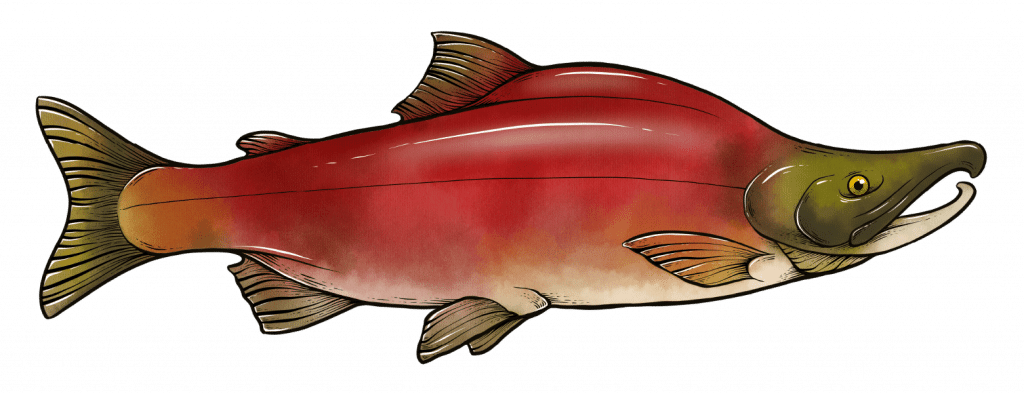

Sockeye Salmon

A.K.A. Red Salmon / Oncorhynchus nerka

Sockeye are a beautiful sight to witness, colouring the rivers and lakes of the Pacific Northwest bright red as groups return for spawning. They have been known to travel vast distances to their preferred spawning grounds. The Fraser, Nass, and Skeena Rivers are major migration routes for these commercially important fish. After hatching in freshwater, juvenile sockeye salmon remain in their natal habitat for as much as three years, longer than any of the other five wild pacific salmon species.